Publications /

Policy Brief

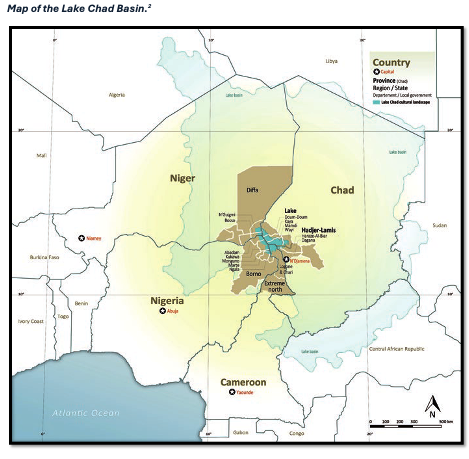

The Lake Chad Basin is home to over 3 million internally displaced persons (IDPs),[1] a number expected to rise due to the recent flooding affecting Chad, Niger, Nigeria, and Cameroon since August. While the primary cause of displacement remains the ongoing violent conflict in the region, the climate crisis is exacerbating existing vulnerabilities and, in the short-term, spurring new waves of displacement in areas already hosting large populations displaced by conflict and insecurity. Climate shocks may also prompt both seasonal and permanent migration within and potentially beyond the region.

Introduction

Since early August, areas surrounding the Lake Chad Basin in Cameroon, Niger, Chad, and Nigeria have been hit by torrential rains, resulting in widespread flooding. Hundreds of people have lost their lives and, beyond the extensive damage to homes, key public service buildings, including health and education facilities, have been damaged or destroyed. Large swathes of farmland have also been devastated, leaving farmers with ruined crops and herders with lost livestock. As a result, thousands of residents have fled the affected areas, seeking shelter, safety, and access to essential services.

This policy brief is part of a series examining the links between the climate crisis and socioeconomic challenges in conflict-affected areas, focusing here on displacement and migration around the Lake Chad Basin. The regions affected by recent flooding are already grappling with numerous challenges that have displaced at least 3 million people across Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria. Most of these IDPs were forced to leave their homes due to ongoing conflict involving violent extremist organizations (VEOs). However, recurrent climate shocks are likely to prompt further displacement and migration, placing additional strain on state authorities and humanitarian organizations as demand for assistance rises. Critically, national, regional, and international actors must work toward a realistic strategy to address climate change in the Lake Chad Basin.

This policy brief draws on open-source research and interviews conducted with recently displaced persons in Chad, Niger, and Cameroon.

Devastating Flooding

Since late August, parts of West and Central Africa, including the Lake Chad Basin, have experienced catastrophic rainfall. Reports indicate that at least 1,500 people have lost their lives, and more than 1 million have been displaced across Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, and Niger.[3],[4] Borno State in Nigeria was particularly affected when a dam burst, flooding the city of Maiduguri and displacing 70% of the its 870,000 inhabitants, with at least 269 fatalities.[5] This disaster was driven by climate change-induced extreme rainfall, compounded by human actions that have degraded the environment.[6]

Local residents, noticing unusually heavy rainfall and rising reservoir levels, had reportedly alerted officials. However, a visiting delegation assessed the situation and concluded that no action was necessary.[7] Four days later, the dam failed, and the resulting flood submerged half the city overnight.[8] Experts point to poor management and neglect as factors that exacerbated the disaster’s impact.[9] According to recent updates, 414,000 people have been displaced and 30 lives lost due to the floods,[10] marking it as Borno’s worst flood disaster in three decades, according to the UN.[11]

Hundreds of thousands of displaced persons are now sheltering in Bakassi Camp and other centers, which until last year primarily housed those fleeing the Jihadist insurgency. These four camps currently host around 6,000 individuals, while thousands more remain in urgent need of assistance. Conditions in the camps are dire, marked by hunger, inadequate medical care, long waits for doctors, and a prevailing sense of despair. Health professionals are increasingly concerned about outbreaks of waterborne diseases, such as cholera, as the city’s sewer system deteriorates. Adding to the crisis, there are no immediate plans for reconstructing the damaged dam—a project unlikely to succeed without federal government support.[12]

In Cameroon, flooding has impacted at least 365,000 people and claimed over 30 lives.[13] More than 56,084 houses have been destroyed, along with 82,509 hectares of farmland submerged and over 5,000 livestock lost. Schools, health centers, and other public services buildings have also been damaged, leaving thousands without access to essential services. Residents in affected areas confirm that many have been forced to flee to regions untouched by the flooding to regain access to these vital services. One displaced person in northern Cameroon shared, “These [affected] populations moved to the city in order to find shelter and have access to assistance such as temporary housing, basic necessities, food assistance, healthcare, and psychological assistance.”[14] Among those displaced are farmers, herders, and community members whose homes and lands have been destroyed.[15] “The floods have caused displacement of people with their belongings, especially […] herders who move with their herds, farmers who also move in order to find less affected land to practice their farming activities, and others to find shelter.”[16]

In Chad, almost 2 million people have been affected by the flooding, with 576 lives lost.[17] The Logone and Chari Rivers have reached unprecedented levels, leading to extensive destruction of farmland and significant crop losses.[18] As a result, many residents have been forced to flee in search of safety and assistance. A displaced person in Chad shared: “These displacements are observed in the localities of the two provinces [Lac and Hadjer-Lamis] but more severely in the villages and islands of the Lac Province. The displaced are mainly farmers and herders. Some fishermen are also affected, but the majority of the displaced people come from the agricultural and pastoral sectors.”[19] Communities in and around the lake rely heavily on fishing, farming, and livestock herding for income. Another individual noted that this displacement could strain host communities: “Displaced people are mainly moving to dry land away from flooded areas. They are seeking shelter in temporary camps or with members of their community, which can put pressure on resources in host areas.”[20] In response, UN agencies have called for urgent aid to support both the displaced and the host communities.

Niger’s areas bordering the Lake Chad Basin were the least impacted by the flooding. While the floods did not result in displacement, they did destroy farmland and crops, according to interviews with affected communities. “People affected did not [have to] move anywhere in the localities of the Diffa region where we experienced floods, but fields have been ravaged.”[21] Farming is a key economic activity and food source in Niger’s Diffa region and, with lost income and food insecurity, some farmers may be inclined to migrate, at least temporarily.

Climate, Migration, Displacement

There is a substantial body of ample academic and gray literature addressing climate change-induced migration and climate refugees. While “climate refugee” is not yet a recognized legal concept under international law, leaving those displaced by climate-crisis disasters without formal protection, they remain particularly vulnerable. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to the ten most climate-vulnerable countries, where displacement often results from deforestation and land degradation, as the loss of arable lands and pastures fuels conflict. Violence between farmers and herders, from Mali to Nigeria, exacerbates instability and livelihood insecurity, while armed group mobilization and intercommunal conflict are creating new migration patterns in the region.[22]

The Lake Chad Basin is one of the world’s most threatened natural resources, with its shrinking waters having displaced around 4.5 million people over the last 50 years, including IDPs, refugees, and returnees.[23] The effects of global temperature rise on the lake are evident, with decreased and irregular rainfall, recurring droughts, low water levels, and the loss of native plant and animal species. Water scarcity has severely impacted farming, fishing, and pastoral livelihoods, leading to food insecurity, limited livelihood options, extreme poverty, and rising intercommunal tensions and violence—all of which drive further displacement. Compounding these challenges are mismatched government responses and human activities, including the expansion of farming and fishing into new landscapes, which have degraded soil fertility and aquatic ecosystems, accelerating the area’s natural decline.[24]

Mobility as Climate Adaptation

Mobility is a common adaptation strategy in response to slow-onset climate changes, making climate-induced migration a critical public policy issue.[25] To cope with shifting climates and economic difficulties, local populations often engage in long-term regional migration, typically following rainfall patterns, or undertake seasonal migration aligned with environmental conditions.[26] Migration frequently becomes a last resort when environmental degradation eliminates livelihood options and alternative income or adaptation strategies are unavailable. Climate migration rarely crosses national borders: in the West Africa-Sahel and Lake Chad Basin, most movement occurs within the region, differing from migration patterns directed toward Europe or North Africa. As populations reliant on rain-fed agriculture migrate to urban centers for better access to services and resources, climate change intensifies the risks and challenges tied to urbanization. Effective political, cultural, social and economic leadership is essential to strengthen communities’ adaptive capacity.[27]

The climate crisis is arguably the greatest threat of contemporary history, impacting all core sectors of society—food and agriculture, water, health, energy, industry, spatial planning, and biodiversity.[28] Its effects are cyclical, driving displacement, population pressures, and vulnerabilities often rooted in conflict dynamics. For instance, Maiduguri’s dense population stems from its relative safety compared to the rural areas of impoverished Borno State, where VEOs remain active. Recent floods have intensified rural-urban migration patterns driven by conflict and climate catastrophes, leading to further internal displacement. These converging factors strain natural resources, water, food supplies, infrastructure, and governance frameworks, perpetuating cycles of crisis.

Displacement itself can also exacerbate conflict dynamics and pose significant policy challenges. In Cameroon and Chad, locals anticipate tensions between IDPs and host communities due to several factors.[29] First, competition for limited resources, such as water, agricultural land, and jobs, can increase as IDP numbers grow. Second, cultural and linguistic differences may lead to misunderstandings and conflict, making intercultural awareness essential. Third, with host communities already facing economic hardships, the influx of IDPs can fuel frustration. Fourth, given the region’s security context, IDPs may be perceived as a threat, further heightening tensions.[30] Addressing these complex challenges requires strategic policy responses that go beyond treating symptoms, addressing the underlying dynamics of climate resilience, ecosystem health, and income security.

Analysis and Policy Recommendations

The Lake Chad Basin experienced a severe climate shock during the 2022 rainy season, which typically spans from May to October. The flooding that year resulted in hundreds of fatalities, damaged hundreds of thousands of hectares of land, and displaced over a million people. Although addressing security challenges around the Lake Chad Basin remains a priority, national and international actors should consider implementing practical and effectives measures to address and mitigate the impact of climate change on local communities.

- Prevention efforts: There is a growing trend of intense rainfall over short periods, leading to frequent flooding that devastates rural communities already struggling with poverty and conflict. These communities rely on farming, herding, and fishing, livelihoods that are increasingly at risk if these climate shocks persist. Consequently, populations in these areas are being forced to abandon their homes in search of safety, essential public services, and alternative income sources. National governments around the Lake Chad Basin, in collaboration with international partners, should prioritize prevention efforts to mitigate the damage from these climate shocks. For example, de-sealing soil surfaces and reinstating natural floodplains allows more rainwater to infiltrate in the soil. Green cover leads water into the ground that would otherwise flow away on concrete surfaces. Similarly, regenerative agriculture practices increase water infiltration and retention rates, which not only helps prevent floods but also mitigates droughts.

- Rise of river waters: The rising river waters in Chad, Cameroon, and Nigeria caused significant physical and human damage during the 2022 and 2024 floods. While climate shocks are challenging to prevent, today’s technology can help predict rainfall levels. Authorities could, therefore, invest in building sand barriers to counter rising river waters when forecasts indicate heavy rains. As seen in the accompanying image, local communities, with support from national and international organizations, are already engaging in efforts in Cameroon.

- Construction and maintenance of dams: In 2022, flooding in Cameroon was partially triggered by a dam being overwhelmed by rainfall, compounded by the failure to complete another dam on the Nigerian side of the same river.[31] Similarly, in 2024, locals in Maiduguri, Nigeria, warned authorities of damage to the dam before it collapsed. Both incidents were the result of human error and could have been prevented. Authorities should prioritize the maintenance of existing dams ahead of the rainy season and plan for the construction of new dams to prevent similar disasters in the future.

- Food security: Fishing, farming, and livestock herding are vital economic activities for local communities and essential source of daily food. The loss of these livelihoods due to climate shocks will expose the population to greater risks of food insecurity. National and international partners must invest in protecting these key sectors to prevent further displacement and migration to urban centers. Local food systems must prioritize food sovereignty, diversifying regional production and lowering the area’s reliance on food imports. Diversifying crop systems, focusing on native breeds, and integrating livestock into arable and grassland create more resilient agriculture and healthier soils that are better suited to a changing climate.

Conclusion

The Lake Chad Basin is an area where local communities are highly vulnerable to climate shocks. The rising water levels have caused major destruction at least twice in the past five years, and such events are likely to occur again in the future. This trend will continue to directly impact communities already grappling with other challenges. The destruction of key local economies such as farming, herding, and fishing is forcing families to migrate in search of work, alternative livelihoods, and food security. Damage to public services further drives families to flee to areas where they can access education and healthcare.

Migration and displacement are rarely the first choice for communities affected by climate change. While some populations may resort to temporary or seasonal migration to survive the crisis, the increasing frequency of climate-related disasters is likely to result in permanent displacement toward urban centers. National actors struggle to address these issues due to limited priorities, resources, and expertise. Therefore, regional and international collaboration is essential, particularly in the Lake Chad Basin, which spans four countries.

Authors Biographies

Rida Lyammouri is a senior West Africa and Lake Chad Basin researcher and advisor, with expertise in regional conflicts, violent extremism, climate change, migration, and trafficking. He specialises in analysing climate-conflict interactions in the Lake Chad Basin, West Africa, and the Sahel, studying resource scarcity, adaptive strategies, and socio-economic impacts. His multidisciplinary approach combines climate science and conflict analysis, offering insights into the region's climate-security nexus.

Boglarka Bozsogi is a regeneration advocate, researching the agroecological transformation of food and farming systems. Holding an MS in Foreign Service from Georgetown University and an MA in International Relations from the University of Birmingham, she has diverse experiences in policy analysis, project management, and events planning around conflict, development, and agriculture.

[1] International Organization of Migration, “West and Central Africa — Lake Chad Basin Crisis Monthly Dashboard 68 (September 2024),” October 2024, https://dtm.iom.int/reports/west-and-central-africa-lake-chad-basin-crisis-monthly-dashboard-68-september-2024#:~:text=As%20of%20September%202024%2C%20Cameroon,from%20February%20to%20April%202024.

[2] Researchgate.net, Map Created by Sébastien Moriset, Accessed on October 2024, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-of-the-Lake-Chad-Basin-C-Sebastien-Moriset-The-names-and-boundaries-shown-and-the_fig1_368967445

[3] Reuters, “Climate change worsened rains in flood-hit African regions, scientists say,” 22 October 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/climate-change-worsened-rains-flood-hit-african-regions-scientists-say-2024-10-23/#:~:text=This%20year's%20floods%20killed%20around%201%2C500%20people,also%20overwhelmed%20dams%20in%20Nigeria%20and%20Sudan.

[4]Ahmed Kingimi, “Nigerian flood victims face long wait for medical help,” 17 September 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerian-flood-victims-face-long-wait-medical-help-2024-09-16/.

[5]Shanna Handbury, “Heavy rains in Lake Chad Basin leave hundreds dead across countries,” 20 September 2024, https://news.mongabay.com/short-article/heavy-rains-in-lake-chad-basin-leave-hundreds-dead-across-countries/.

[6]Ahmed Kingimi, “Nigerian flood victims face long wait for medical help,” 17 September 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/nigerian-flood-victims-face-long-wait-medical-help-2024-09-16/.

[7] Azeezat Olaoluwa, “I thought I would die with my six children' - dam collapse survivor,” 12 September 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy0r0jnp254o

[8]Azeezat Olaoluwa, “I thought I would die with my six children' - dam collapse survivor,” 12 September 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy0r0jnp254o

[9]Shanna Handbury, “Heavy rains in Lake Chad Basin leave hundreds dead across countries,” 20 September 2024, https://news.mongabay.com/short-article/heavy-rains-in-lake-chad-basin-leave-hundreds-dead-across-countries/.

[10]Gift Oba, “Maiduguri flood: Ogun Govt donates N200m to Borno State,” 05 October 2024, https://dailypost.ng/2024/10/05/maiduguri-flood-ogun-govt-donates-n200m-to-borno-state/

[11]Azeezat Olaoluwa, “I thought I would die with my six children' - dam collapse survivor,” 12 September 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy0r0jnp254o.

[12] Azeezat Olaoluwa, “I thought I would die with my six children' - dam collapse survivor,” 12 September 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy0r0jnp254o

[13] OCHA, “Cameroon – Extreme-Nord, Note d’Information sur Les Inondations,” 19 September 2024.

[14] Interview with displaced person from Extreme-Nord region of Cameroon, October 2024.

[15] Interviews with affected families in Extreme-Nord region of Cameroon and Lac Province of Chad, October 2024.

[16] Interview with displaced person from Extreme-Nord region of Cameroon, October 2024.

[17]Reliefweb, “UNICEF Chad Flash Update No.4 (Floods) – 25 October 2024,” 25 October 2024, https://reliefweb.int/report/chad/unicef-chad-flash-update-no-4-floods-25-october-2024

[18] TV5 Monde, “Tchad : mobilisation générale face aux inondations,” 11 October 2024, https://information.tv5monde.com/afrique/video/tchad-mobilisation-generale-face-aux-inondations-2743786

[19] Interview with displaced person from Lac Province of Chad, October 2024.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Interview with affected communities in Tam, Diffa region, Niger, October 2024.

[22] Jaldi, Abdessalam, and Amal El Ouassif, Climate Refugees: A Major Challenge of International Community and Africa, PCNS, June 2022.

[23] Jaldi, Abdessalam, and Amal El Ouassif, Climate Refugees: A Major Challenge of International Community and Africa, PCNS, June 2022.

[24] Jaldi, Abdessalam, and Amal El Ouassif, Climate Refugees: A Major Challenge of International Community and Africa, PCNS, June 2022.

[25] Climate change and migration: Understanding factors, developing opportunities in the Sahel Zone, West Africa and the Maghreb.

[26] EVANS, MARTIN, and YASIR MOHIELDEEN. “Environmental Change and Livelihood Strategies: The Case of Lake Chad.” Geography 87, no. 1 (2002): 3–13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40573633.

[27] Climate change and migration: Understanding factors, developing opportunities in the Sahel Zone, West Africa and the Maghreb.

[28] Climate change and migration: Understanding factors, developing opportunities in the Sahel Zone, West Africa and the Maghreb.

[29] Interviews with affected families in Extreme-Nord region of Cameroon and Lac Province of Chad, October 2024.

[30]Interviews with affected families in Extreme-Nord region of Cameroon and Lac Province of Chad, October 2024.

[31] World Weather Attribution, “Climate change exacerbated heavy rainfall leading to large scale flooding in highly vulnerable communities in West Africa,” 16 November 2022, https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/climate-change-exacerbated-heavy-rainfall-leading-to-large-scale-flooding-in-highly-vulnerable-communities-in-west-africa/