Publications /

Opinion

While global attention has been focused on the Houthi rebel attacks in the Red Sea, Somali pirates have seized the opportunity to escalate their own attacks and violence along these strategic waterways. The threat is increasing dramatically due to an emerging network of allies between Al-Shabaab, the Houthis, and Somali pirates, as well as overlapping national and international factors.

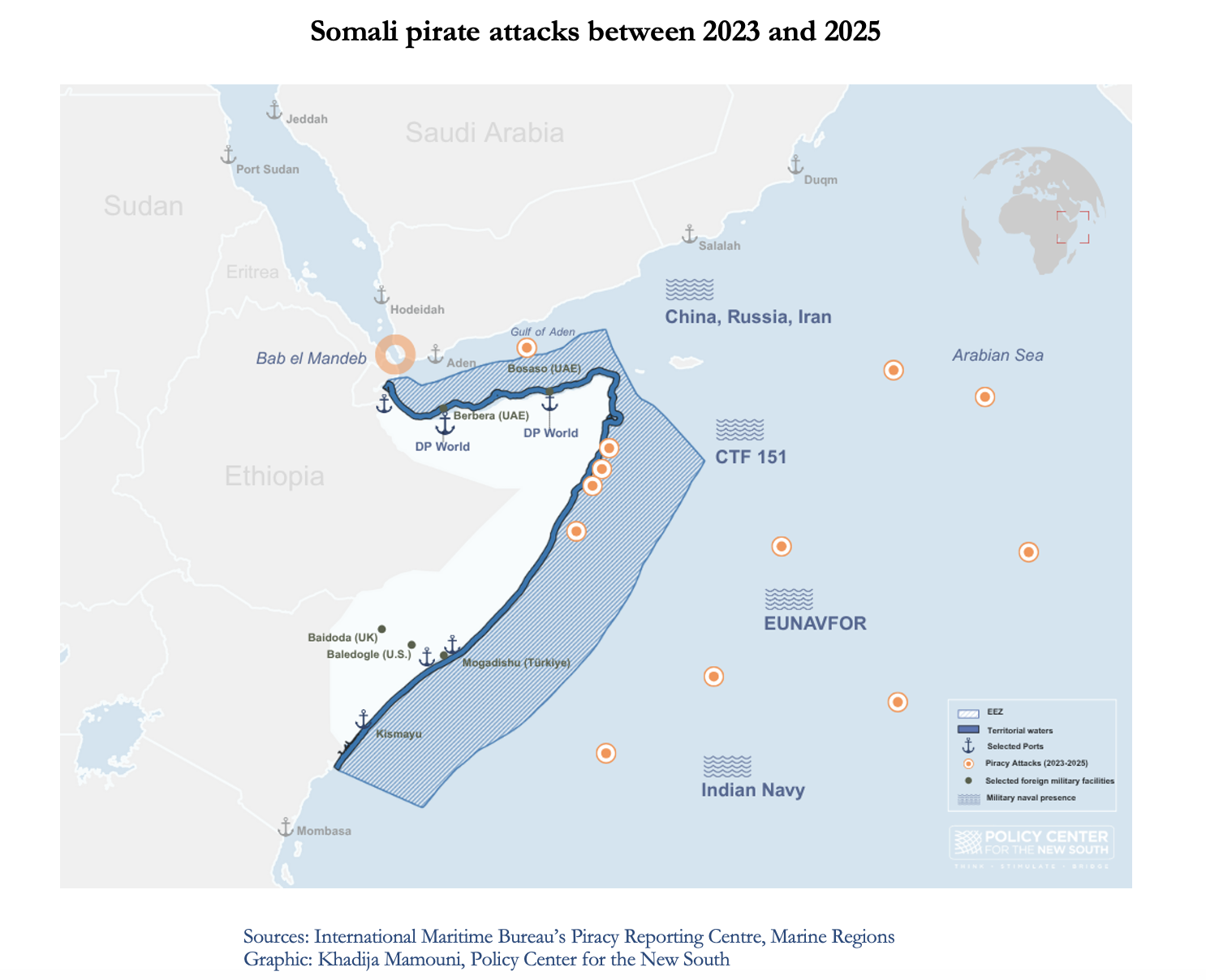

The first successful Somali piracy incident since 2017 took place in December 2023, a month after Houthi rebels began attacking and seizing merchant ships in the area, which was en route from Singapore to Türkiye. The attack occurred around 700 nautical miles east of Bosaso in Somalia.[1] According to the MICA Maritime Security 2024 annual report, “After several years of decline, piracy is on the rise again (+110% in one year), particularly off the coast of Somalia.”[2] “Between 7 February and 16 March 2025, two fishing vessels and a dhow were hijacked off the coast of Somalia,” according to the International Maritime Bureau.[3] Somali piracy cost the shipping industry and governments almost USD 7 billion in 2011 during its peak.[4] The current surge may not match the risks posed in 2011, but it is unfolding within a novel and complex web of criminal activity.

What is New?

Compared to the 2000s, when piracy attacks were concentrated around Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden, Somali piracy in 2023 and 2024 has spread out hundreds of miles into the Indian Ocean. Pirates’ technological capabilities are also growing, with attacks often involving multiple armed assailants, Kalashnikov-style rifles, and rocket-propelled grenades.[5] These pirates are commandeering dhows and fishing vessels as ‘mother ships’. This allows the pirates to carry out activities far beyond their territorial waters. The growing multi-layered criminal network of pirates in Somalia is also complexifying this phenomenon. Their expanding operational range, growing technological capabilities, and support from wealthy and powerful individuals have turned piracy into a more sophisticated business. Some researchers apply the “greed and grievance” framework to explain the spread of piracy in Somalia. They argue that while grievances such as illegal fishing and poverty drove its initial emergence, piracy has since transformed from “a haphazard activity into a highly organized criminal enterprise.”[6]

What Is Driving This Re-emergence?

The resurgence of piracy is caused by many overlapping causes, including local fishermen’s frustration with foreign trawlers’ overfishing and the deterioration of security arrangements impeding piracy. Somali security forces are focused on countering jihadi activity and maintaining control of the town of Las Anod.[7] Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing off the Somali coast, exercised by foreign vessels from Iran, India, and Pakistan, costs Somalia around USD 300 million yearly, detracting from economic growth, damaging marine resources, and increasing local grievances.[8] One researcher has likened this to an imbalanced “resource swap,” with maritime resources enriching foreign fishing trawlers far more than the ransoms do for pirates.[9]

Importantly, piracy is emerging while international maritime security measures securing the Somali coast have been reduced due to dwindling attacks. In March 2022, the UN Security Council did not extend the resolution authorizing international navies to counter piracy, and in January 2023, the shipping industry removed the Indian Ocean High Risk Area designation. As a consequence, the frequency of anti-piracy patrols off Somalia has diminished. At the same time, the Houthis’ attacks on the Red Sea have diverted naval forces’ attention from the piracy threat. Cohen and Felson’s theory of crime argues that crimes occur due to three converging factors: an easy target, a motivated offender, and the absence of a capable guardian. We can see that these three factors have laid the ground for a perfect opportunity for Somali pirates.

The Houthis, Al-Shabaab, and Somali Pirates Circle

The Houthis are not merely diverting international attention; their expanding coordination with Al-Shabaab is also implicitly contributing to the resurgence of maritime piracy in the region. According to a UN report, the Houthis are cooperating with the al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Shabaab in Somalia to further facilitate the movement of both illicit and licit goods.[10] In February 2025, the United Nations reported evidence of physical meetings taking place between the Houthis and Al-Shabaab in 2024.[11] Al-Shabaab requested advanced weapons and training. In exchange, Al-Shabaab agreed to increase piracy activities in the Gulf of Aden and off the coast of Somalia, attacking cargo ships, interfering with maritime traffic, and collecting ransom from the captured vessels. The two groups have transcended the Sunni-Shia divide to establish a new transactional and opportunistic alliance. Experts speculate that Al-Shabaab militants are exploiting this momentum to broker deals for ransom proceeds and loot cuts in exchange for protecting pirates.[12] Vice Admiral Ignacio Villanueva Serrano, commander of the European Union operation countering piracy, has said that these new pirates are well coordinated with satellite phones and heavy weapons, and weapon sales by Al-Shabaab from the Houthis are solidifying the groups’ commercial ties. Evidence of increased smuggling activities, particularly involving small arms and light weapons, indicates security and intelligence cooperation between the two groups.

Diversifying Counter-Piracy Responses with Türkiye and India

Somalia is outsourcing its protection of marine resources for the next decade to Türkiye under an MoU signed in February 2024. The pact offers Somalia’s naval forces the training and equipment to fight illegal fishing in the waterways of Somalia in exchange for granting Türkiye control of the hydrocarbons deal and 30% of the revenue from Somalia’s exclusive economic zone. In addition, India is proving to be an important rapid response force against piracy, proven by its successful rescue of the Ruen’s 17 crew members. As maritime stakes rise, small and middle powers are stepping in to contain threats as well as recalibrating the balance of influence in the Indian Ocean.

Conclusion

Peace for Somalia remains uncertain, with internal political disputes, illegal fishing, unemployment, and poverty continuing to fuel grievances. These vulnerabilities, combined with the rise of new criminal networks and widening opportunity gaps, are creating fertile ground for piracy’s possible return. Although the current wave remains limited in scale, it nonetheless requires adaptation from the maritime industry to understand the novel tactics deployed by these groups and to assess the risks rationally.

Research has shown that the most successful counter-piracy measures are: “naval patrols, extensive coordination, self-protection, notably use of armed guards, and capacity-building enabling pirate prosecution.”[13] Limited, targeted interventions that address specific threats are likely to be more effective than broad mandates. Somali leaders are increasingly alarmed; “If we do not stop it while it’s still in its infancy, it can become the same as it was,” warned President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud.

Bibliography

ADF. “Somali Piracy Surges as New Threat Diverts Resources.” Africa Defense Forum, June 18, 2024. https://adf-magazine.com/2024/06/somali-piracy-surges-as-new-threat-diverts-resources/.

Bowden, Anna “The Economic Cost of Somali Piracy 2011.” Oceans Beyond Piracy: One Earth Future Foundation, February 2, 2012.

Clayton, Hassan-kafi Mohamed and Jonathan. “Al Shabab Shows Its Reach on Land as It Ventures into Piracy on the High Seas.” The National, December 29, 2023. https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/africa/2023/12/29/al-shabab-shows-its-reach-on-land-as-it-ventures-into-piracy-on-the-high-seas/.

Cohen, Lawrence E, and Marcus Felson. “Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach.” American Sociological Review 44, no. 4 (August 1979): 588–608. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2094589.

Elmi, Afyare A., Ladan Affi, W. Andy Knight, and Said Mohamed. “Piracy in the Horn of Africa Waters: Definitions, History, and Modern Causes.” African Security 8, no. 3 (July 3, 2015): 147–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2015.1069118.

Giulia Paravicini, Jonathan Saul, and Abdiqani Hassan. “Somali Pirates Return, Adding to Global Shipping Crisis.” Reuters, March 21, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somali-pirates-return-adds-crisis-global-shipping-companies-2024-03-21/.

International Chamber of Commerce. “New IMB Report Reveals Concerning Rise in Maritime Piracy Incidents in 2023.” ICC - International Chamber of Commerce, January 11, 2024. https://iccwbo.org/news-publications/news/new-imb-report-reveals-concerning-rise-in-maritime-piracy-incidents-in-2023/.

International Chamber of Shipping. “Shipping Industry to Remove the Indian Ocean High Risk Area.” Ics-shipping.org, August 22, 2022. https://www.ics-shipping.org/press-release/shipping-industry-to-remove-the-indian-ocean-high-risk-area/.

International Commercial Crime Services. “Pronounced Spike in Low-Level Crimes in Singapore Straits – ICC – Commercial Crime Services.” Icc-ccs.org, 2025. https://icc-ccs.org/pronounced-spike-in-low-level-crimes-in-singapore-straits/.

Lehr, Peter. “Somalia—Pirates’ New Paradise.” In Violence at Sea: Piracy in the Age of Global Terrorism. Routledge, 2006.

Mahmood, Omar. “The Roots of Somalia’s Slow Piracy Resurgence | Crisis Group.” www.crisisgroup.org, June 7, 2024. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/roots-somalias-slow-piracy-resurgence.

Maritime Information Cooperation & Awareness Center. “Publication of the MICA Center’s 2024 Annual Report – MICA Center – Maritime Information Cooperation & Awareness Center.” Mica-center.org, 2024. https://www.mica-center.org/en/publication-of-the-mica-centers-2024-annual-report/.

Peter Viggo Jakobsen, and Troels Burchall Henningsen. “Success Defying All Expectations: How and Why Limited Use of Force Helped to End Somali Piracy.” Journal of Strategic Studies, June 21, 2023, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2023.2227356.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. “Tackling Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing in Somalia.” https://www.unodc.org/, March 2023. https://www.unodc.org/easternafrica/en/Stories/tackling-illegal--unreported--and-unregulated-fishing-in-somalia.html.

[1] International Chamber of Commerce, “New IMB Report Reveals Concerning Rise in Maritime Piracy Incidents in 2023,” ICC - International Chamber of Commerce, January 11, 2024,https://iccwbo.org/news-publications/news/new-imb-report-reveals-concerning-rise-in-maritime-piracy-incidents-in-2023/.

[2] Maritime Information Cooperation & Awareness Center, “Publication of the MICA Center’s 2024 Annual Report – MICA Center – Maritime Information Cooperation & Awareness Center,” Mica-center.org, 2024,https://www.mica-center.org/en/publication-of-the-mica-centers-2024-annual-report/.

[3] International Commercial Crime Services, “Pronounced Spike in Low-Level Crimes in Singapore Straits – ICC – Commercial Crime Services,” Icc-ccs.org, 2025,https://icc-ccs.org/pronounced-spike-in-low-level-crimes-in-singapore-straits/.

[4] Anna Bowden, “The Economic Cost of Somali Piracy 2011” (Oceans Beyond Piracy: One Earth Future Foundation, February 2, 2012).

[5] ADF, “Somali Piracy Surges as New Threat Diverts Resources,” Africa Defense Forum, June 18, 2024,https://adf-magazine.com/2024/06/somali-piracy-surges-as-new-threat-diverts-resources/.

[6] Afyare A. Elmi et al., “Piracy in the Horn of Africa Waters: Definitions, History, and Modern Causes,” African Security 8, no. 3 (July 3, 2015): 147–65,https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2015.1069118.

[7] Omar Mahmood, “The Roots of Somalia’s Slow Piracy Resurgence | Crisis Group,” www.crisisgroup.org, June 7, 2024, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/roots-somalias-slow-piracy-resurgence.

[8] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “Tackling Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing in Somalia,” https://www.unodc.org/, March 2023,https://www.unodc.org/easternafrica/en/Stories/tackling-illegal--unreported--and-unregulated-fishing-in-somalia.html.

[9] Peter Lehr, “Somalia—Pirates’ New Paradise,” in Violence at Sea: Piracy in the Age of Global Terrorism (Routledge, 2006).

[10] UN Security Council, “Letter Dated 11 October 2024 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen Addressed to the President of the Security Council” (United Nations, October 11, 2024).

[11] United Nations Security Council (UNSC), "Letter Dated 6 February 2025 from the President of the Security Council Addressed to the President of the Security Council," S/2025/71, 6 February 2025.

[12] Hassan-kafi Mohamed and Jonathan Clayton, “Al Shabab Shows Its Reach on Land as It Ventures into Piracy on the High Seas,” The National, December 29, 2023, https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/africa/2023/12/29/al-shabab-shows-its-reach-on-land-as-it-ventures-into-piracy-on-the-high-seas/.

[13] Peter Viggo Jakobsen and Troels Burchall Henningsen, “Success Defying All Expectations: How and Why Limited Use of Force Helped to End Somali Piracy,” Journal of Strategic Studies, June 21, 2023, 1–25, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2023.2227356.