Publications /

Policy Brief

The Mattei Plan, launched by far-right Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, aims to redefine Italy’s engagement with Africa through a strategic blend of political vision, development cooperation, and economic diplomacy. Framed as a non- predatory alternative to traditional models, the Plan seeks to position Italy as a credible and constructive partner by promoting co-creation with African stakeholders and delivering concrete, results-oriented projects. Central to its approach is the consolidation of Italy’s overseas development assistance (ODA) governance, the deployment of financial instruments via the African Development Bank, and partnerships across five priority sectors: education, health, energy, agriculture, and water. While the Mattei Plan marks a departure from Italy’s previously fragmented initiatives, it faces critical scrutiny over potential contradictions-particularly concerning extractivist practices and migration politics. This paper assesses whether the Plan constitutes a genuine shift in Italy’s Africa policy or a tactical repackaging of national interests. It also explores how the Plan intersects with broader initiatives such as the EU Global Gateway and G7’s PGII, and whether it can evolve from a nationalist project into a multilateral tool for transregional cooperation. Ultimately, the Mattei Plan serves as a test of Italy’s ability to balance ambition with credibility.

Introduction

On October 25, 2022, during her inaugural address, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni announced the launch of a "Mattei Plan for Africa"¾an initiative that was both ambitious and symbolic. Presented as a new model of cooperation between Italy, the EU, and African nations, the plan aims to tackle the root causes of irregular migration and to address security threats, particularly those linked to radical Islamism. By invoking the legacy of Enrico Mattei—a pivotal figure in Italy’s post-war energy independence, never achieved in full¾Meloni offers a strategic and identity-driven reinterpretation of Italy’s role on the African stage. This reference is far from incidental; it reflects a desire to redefine Italian foreign policy in a geopolitical context marked by the war in Ukraine, growing migratory pressures, and the gradual retreat of some traditional powers from Africa.

However, beyond the initial announcement, the Mattei Plan remains primarily a political statement, lacking a fully articulated program or an immediate implementation roadmap. The initiatives appears to embody both continuity and rupture in Italy’s approach to Africa: continuity in the involvement of public and private actors already active on the ground (such as ENI), and rupture in the attempt to unify these efforts under a coherent national and strategic framework.

So, what does the Mattei Plan reveal about Italy’s ambitions in Africa? Should it be seen as a genuine shift in Italian foreign policy, a political communication strategy, or an effort to reposition Italy within the Mediterranean and African spheres? This article aims to analyze the origins, stakeholders, and prospects of the "Mattei Plan" as an attempt to build an Italian African policy at the crossroads of energy, migration, and geopolitical challenges.

1. A Different Governance Model

The first major action under the Mattei Plan involves a streamlining of the governance of Italian Overseas Development Assistance (ODA). ODA funds from various ministries have been centralized under the direct authority of the Prime Minister. Specifically, €3 billion from the climate fund and €2.5 billion from cooperation funds have been merged into a single €5.5 billion pool, now exclusively earmarked for Africa. This reallocation significantly increases the continent’s share of Italy’s ODA, redirecting unspent funds from other areas.

Beyond longstanding actors such as ENI, Terna, and Leonardo, Italian small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have so far had limited presence on the continent. However, the funding boost¾part of which is designated for de-risking private investment¾has triggered a wave of new cross-sectoral proposals from both Italian businesses and NGOs.[1][2] Relevant personnel have also been brought together under a single technical body, the Struttura di Missione, tasked with planning and overseeing the Mattei Plan.[3] Implementation, however, remains the responsibility of independent agencies such as Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP), Italy’s development bank, and the Italian Agency for Cooperation and Development (AICS), which maintain operational autonomy while applying the necessary checks to the Prime Minister’s office.[4]

The second major shift enhances coordination between Italian stakeholders through the creation of the ad hoc Cabina di Regia, a strategic steering committee that defines the Plan’s political direction. Chaired by the Prime Minister, it brings together ministries, universities, civil society organizations, CDP, public agencies (such as SACE and SIMEST), and major private companies. This forum has improved cooperation and efficiency, unifying what had previously been a patchwork of isolated initiatives.[5]

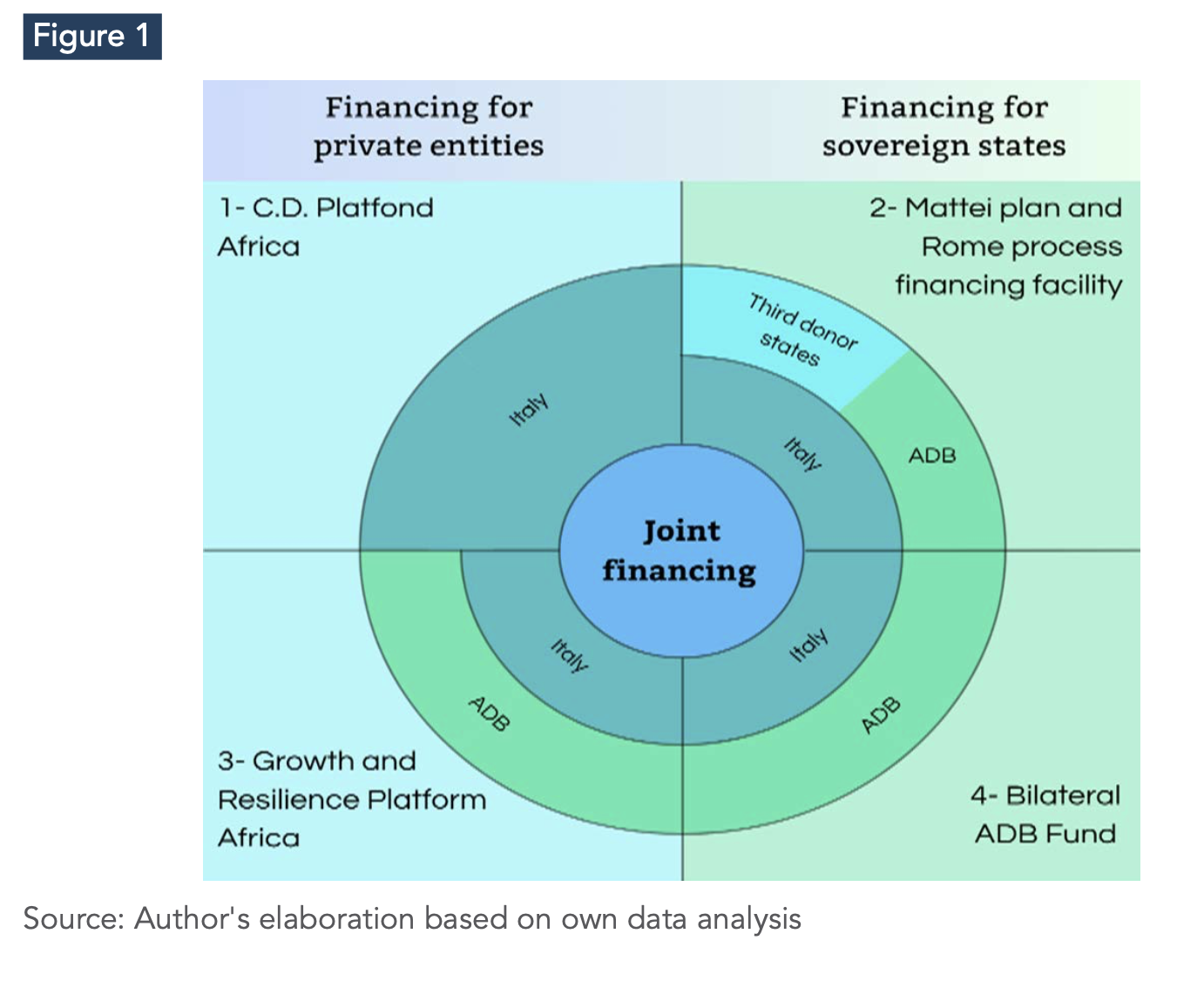

To foster collaboration with external actors, CDP for example has been tasked with developing four financial instruments (see Figure 1) to mobilize capital from other sovereign entities and international financial institutions interested in participating. The additional capital will supplement the current €5.5 billion envelope, helping to de-risk private investment and providing partner countries low-interest loans with a 55.6-year repayment period.[6]

Italy has chosen the African Development Bank (AfDB) as its leading financial partner¾an international decision, given that African states hold a 60% stake of voting rights within the institution. By partnering with the AfDB rather than the Western-led World Bank, Italy is promoting a model of co-creation in which African states participate in the planning, approval, and execution of projects. The AfDB has pledged to match every euro invested by Italy through innovative financial instruments and has already contributed almost €500 million, along with technical expertise. The United Arab Emirates has pledged an additional €100 million, while international financial institutions have joined in co-financing projects such as Elmed and Lobito.[7]

2. International Involvement

The second objective of the Mattei Plan aims to distinguish itself from similar international partnerships. To this end, the plan is named after Enrico Mattei, who is widely regarded as the first European to offer Africa favorable extractive deals, challenging the dominance of “big oil”. Mattei also supported Algerian and Ghanaian independence¾a stance that earned him lasting sympathy across parts of the African continent.[8] By drawing on this historical legacy, Prime Minister Meloni frames the Plan as a revival of Mattei’s vision, presenting it as “a new philosophy of cooperation”[9]one that moves away from extractivism and traditional development in favor of co-creation with African countries.

While other global actors also promote co-creation, entrenched power asymmetries often hinder its genuine implementation. Italy, being a smaller player compared to actors like China, presents a more balanced proposition, making genuine co-creation seem more feasible. In practical terms, this principle has been reflected in the joint steering of the plan by Italy and its African partners. Rather than starting from a predefined list of Italian-led projects, the Mattei Plan allows African countries to participate on their own terms¾bringing forward their priority projects and involving local industries and institutions.[10] Let us note, however, that this remains to be seen, as Italy still holds an almost complete lead in project selection, and unfortunately, the involvement of local stakeholders appears to be limited.

Beyond Italy’s smaller size, what distinguishes the Mattei Plan from other partnerships is its strong emphasis on concreteness. Avoiding vague references to aspirations, principles, and benchmarks, the Plan deliberately distances itself from the historically ambiguous Euro-African discourse by prioritizing what African countries have long demanded: tangible, measurable impact.[11] To maximize the projects' speed and visual impact, the first countries to join were not selected based on historical ties with Italy but because they already had active Mattei-backed projects underway. To maximize the impact of these projects, the plan focuses exclusively on areas where Italian companies and the state can deliver real and effective outcomes. This pragmatic approach sets the Mattei Plan apart from other partnerships, which often overextend into sectors beyond their capacities, thereby diluting their impact on the ground.

Overall, by combining the ideals of co-creation and concreteness, the Mattei Plan stands out as unique. Co-creation differentiates it from initiatives like the Belt and Road initiative, while its result-oriented approach sets it apart from other European and Indian partnerships. Meloni is betting that this dual focus will position Italy as Africa’s privileged European partner. Although it is too early to draw definitive conclusions, some positive feedback has emerged. Since the launch of the Mattei Plan, eight new countries¾previously not recipients of Italy’s ODA¾have established development partnerships with Italy:[12] Morocco, Algeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Congo, Ghana, Angola, Mauritania and Tanzania. Two new AICS offices have been opened in Uganda and Ivory Coast[13] to support cooperation and development efforts. Interest and trust in the Plan’s implementation were further underscored by its 2025 expansion, which added five new countries as well as an association partnership with the EU’s global gateway. Overall, international media coverage of Italy’s renewed engagement in Africa¾largely absent for decades¾signals growing interest in the future of this initiative.

2.1. Global gateway and PGII

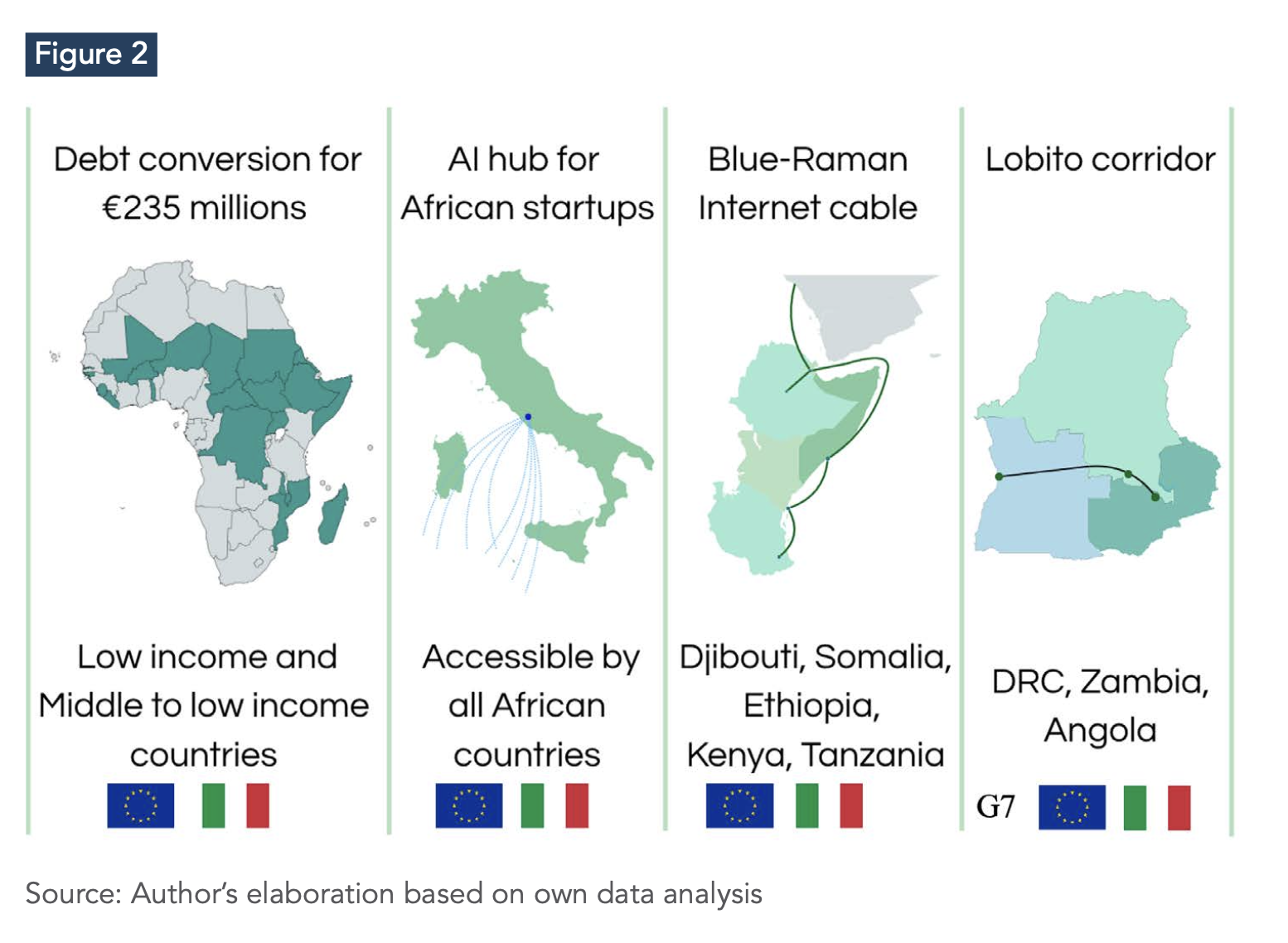

Despite its ambitions and initial momentum, the Mattei Plan on its own lacks the scale to deliver impact at a continental level. To enhance its effectiveness, Italy is aligning its overlapping areas of interest with the EU’s Global Gateway and the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII).

These distinct initiatives with their own priorities, governance, and strategic focus have found synergies in several regional infrastructural projects, as illustrated in Figure 2

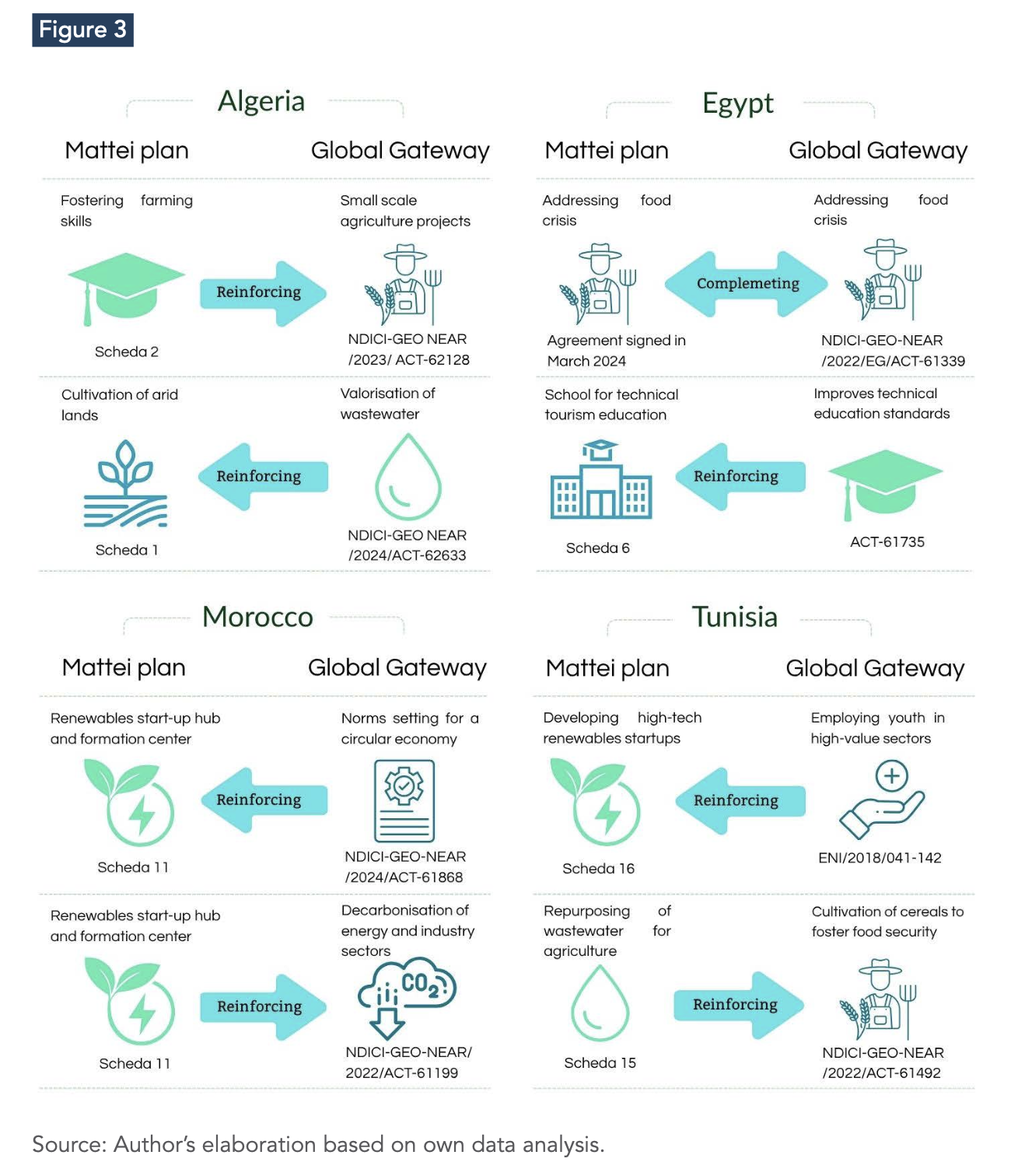

Yet, beyond these regional infrastructural projects, cooperation may also be possible between national-level initiatives carried out within individual countries. Analysis reveals a high degree of compatibility between Mattei Plan projects and those of the Global Gateway in North Africa, as shown in Figure 3. It is reasonable to assume that similar complementarities could also be identified in Sub-Saharan Africa, given the overlapping priorities in agriculture, education, and environmental sustainability.

The benefits of coordination are clear: it helps avoid a fragmented patchwork of isolated projects and instead concentrates efforts to scale impact. The Global Gateway’s scale is considerably larger than that of the Mattei Plan. In North Africa alone, EU public investment between 2021 and 2024 amounts to €1.9 billion¾more than a third of the Mattei Plan’s entire envelope for the continent.[14] Aligning the two frameworks would expand the financial resources available to Mattei-related projects, thereby maximizing Italy’s impact and enhancing its international image.

From the EU’s perspective, associating with Italy offers significant reputational gains. Emphasizing the Mattei Plan’s pragmatism and concreteness can help offset the Global Gateway’s perceived lack of results, strengthening its positioning in comparison to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Moreover, despite the EU’s central position in Africa’s trade and economics, its public image on the continent remains weak: only 49% of Africans view its influence positively, compared to 60% for China.[15] Italy, by contrast, enjoys a comparatively better reputation in Africa, and the Mattei brand has been well received across the continent.[16]

By joining forces, the EU can leverage the strength of Italy’s image to improve its own perception. This is especially relevant in the region of the Alliance of Sahel States, where most western actors¾except Italy¾have been physically expelled.

3. The Mattei projects

The first two objectives of the Mattei Plan¾improved governance and the creation of effective partnerships¾are foundational reforms designed to support the Plan's core objective: delivering the Mattei projects. These are scheduled for implementation between 2024 and 2028, with the possibility of a four-year extension.

Pilot projects began in 2024 in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire, Congo, and Mozambique. In 2025, additional projects were launched in Angola, Ghana, Mauritania, Tanzania, and Senegal.[17] Currently, Italy is engaged in negotiations with Congo, Kenya, Libya, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Côte d'Ivoire to develop further initiatives, particularly in the sectors of agriculture and health.[18] Drawing on its areas of expertise, Italy has organized the Plan’s projects around five core pillars: education and training, agriculture, health, energy, and water¾with infrastructure serving as a cross-cutting sixth pillar.

Overall, the Mattei Plan is poised to have a positive impact on the continent. In some cases, its projects are transferring technology, supporting sustainable energy production, extending food sovereignty, and adding value to local supply chains. They are improving internet access for populations and enabling African start-ups to harness the potential of AI. The Plan also includes debt conversion initiatives for the lowest-income countries, transforming debt into sustainable development projects.

Yet it would be naïve not to question these efforts. Extractive practices and imbalanced partnerships have historically characterized European engagement in Africa; positive externalities lose value if patterns of migration externalization, hydrocarbon extraction, and value chain exploitation persist. Evaluating how these projects are implemented will be key to determining whether the Mattei Plan is truly a plan “with Africa”¾or merely another plan “in Africa.”

3.1. Migration

At first glance, the Mattei Plan could be interpreted as a form of compensation for migration externalization. Meloni herself has repeatedly stated that the goal of the Mattei Plan is to “grant the right not to emigrate.”[19] Framing it this way serves her politically, as migration remains a highly sensitive issue for her domestic base. It allows her to engage with Africa governments under the banner of migration reduction, while simultaneously scoring political points at home.

However, these statements amount largely to political propaganda. None of the Plan's five pillars¾or any of its current projects¾are centered on migration. Moreover, aside from Tunisia, Egypt, and Côte d’Ivoire¾which are indeed important origin and transit countries¾the rest of the Mattei Plan’s partner countries have not significantly contributed to the migration flows arriving in Italy between 2017 and 2023.[20] Even in the case of Tunisia, Egypt and Côte d’Ivoire, it is difficult to establish a clear quid pro quo aimed at reducing migratory pressure, particularly as both Tunisia and Egypt have historically been longstanding cooperation partners of Italy. In reality, Meloni has deliberately crafted the Mattei Plan to be devoid of direct references to migration¾a topic that Italy is instead addressing through the EU Asylum Pact and the Rome Process.

3.2. Extraction of Energy

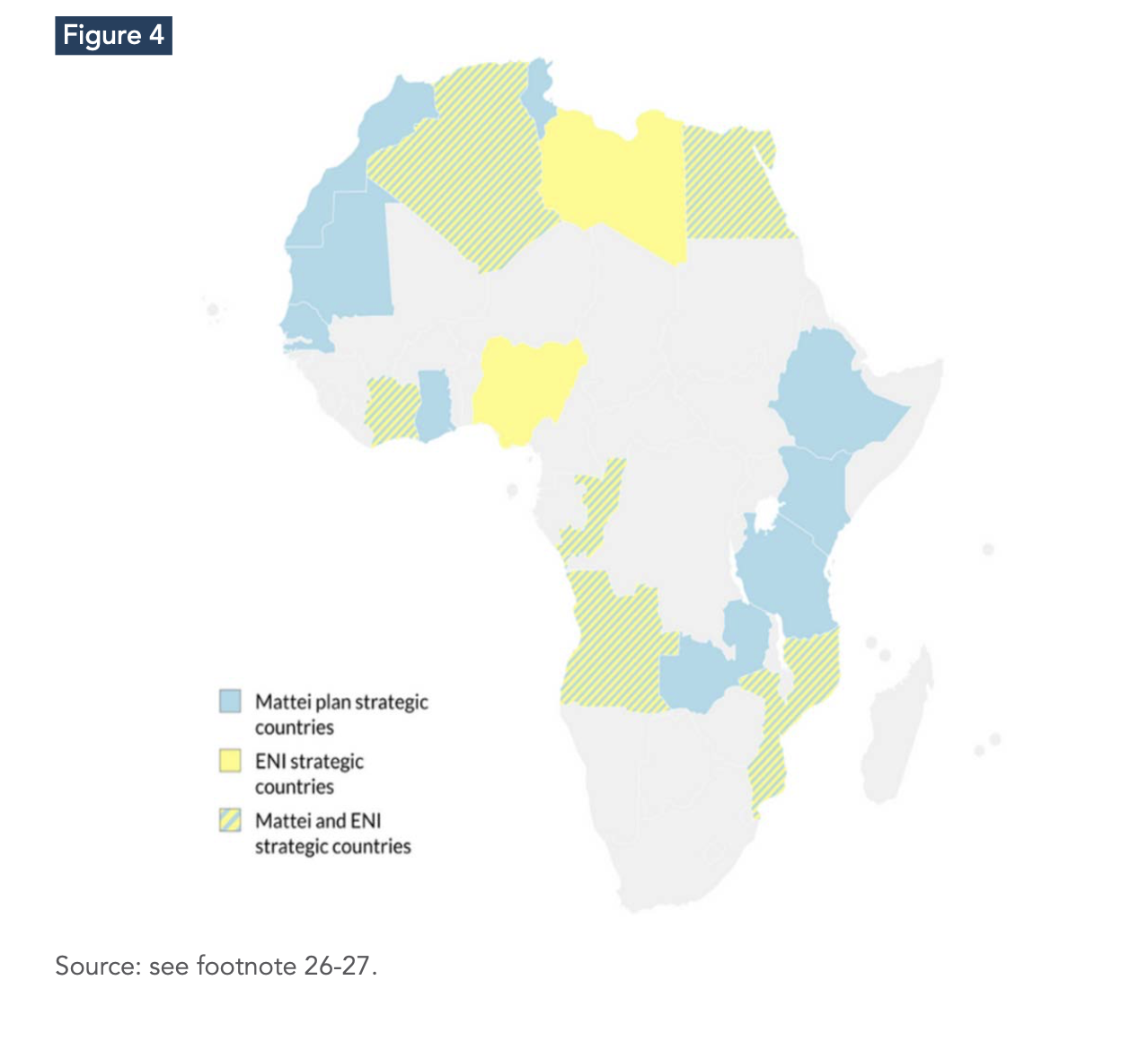

Given the positive impact of the Italian hydrocarbon company, ENI, on Italy’s public finances, leveraging the Mattei Plan to increase revenues may be tempting. However, doing so would contradict the Plan’s stated non-predatory principles. At first glance, there appears to be some geographical overlap between ENI’s operation and the Mattei Plan: ENI has identified eight priority countries in Africa, six of which are also included in the Mattei Plan (as shown in Figure 4).[21] Italy already maintains long-standing cooperation with Egypt and Mozambique, leaving only four of the fourteen countries Mattei partner countries where a potential overlap of interests between ENI and the Plan may arise.[22]

Yet the resources extracted from these four countries are limited in scale. In 2023, Italy imported 8% of its oil needs from all 14 countries involved in the Mattei Plan¾with Algeria alone accounting for 4.1%.[23] In the same year, 42.2% of Italy’s gas imports came from Mattei Plan countries, of which 41.5% came from Algeria.[24] If one were to hypothesize a trade-off between resource access and development projects, Algeria would appear the likely candidate. However, given the relatively limited scope of Italian development projects in Algeria and the financial strength of ENI, it is unlikely that the company would base its long-term investments on the Plan. Indeed, in 2025, ENI announced €26 billion in investments in Egypt, Libya and Algeria.[25] This is just one of ENI’s many investments commitments¾and alone, it exceeds the total Mattei Plan budget by more than four times.

Furthermore, the disbursement of Mattei Plan funds is subject to strict conditionalities. Three billion euros are sourced from Italy’s Climate Fund, which is tied to CDP's stringent earmark 2 environmental goals. These criteria effectively prohibit the use of these funds for hydrocarbon extraction.[26] Instead, they align with the EU’s New Generation Free Trade Agreement standards, indirectly supporting a potential Free Trade Agreement between Africa and the EU. An additional €2.5 billion comes from the IACD, whose earmark 1 guidelines also prohibit spending on extractive activities.[27] Both CDP and IACD operate under procedural and substantive constraints when approving expenditures, making it highly unlikely they these funds could be channeled into partnerships that would favor ENI.

3.3. Lobito corridor

Beyond traditional oil and gas, critical raw materials have rapidly become the new extractive frontier. One Mattei Plan project raises concerns in this regard. The Lobito rail corridor aims to connect Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Zambia to facilitate the export of critical raw materials, while also seeking to diversify its use to promote regional development. The corridor will provide much-needed infrastructure, as requested by the participating African countries.

However, beyond generic promises of “development” and “jobs,” there is no concrete plan to add value to local economies through the corridor. Moreover, regional fragmentation in technical standards, customs regimes, and procedures makes diversification impossible, as seamless two-way logistics are essential. As currently designed, the railway will primarily serve to export critical raw materials¾a pattern reminiscent of the extractive models that enabled European colonizers to deprive Africa of its resources. Unless its use is diversified, the Lobito corridor will remain an extractive project. By participating, Italy risks undermining its normative rhetoric against exploitation.

3.4. Low-Cost Labor for Export

Another dimension of Euro-African exploitation concerns the use of cheap African labor to produce goods for export to Europe. Most of the Mattei Plan’s projects appear to avoid extractivist dynamics; however, two agricultural projects¾in Algeria and Kenya¾have raised concerns in this regard. The Italian Parliament has expressed reservations, warning that these projects could exploit the local population for European benefit.

In the case of Algeria, concerns emerged that extractive agricultural practices might deprive the country of essential food supplies. Algeria is heavily dependent on food imports, and the Algerian president has stated the goal of making 500,000 hectares arable to ensure domestic food security and support exports to neighboring countries.[28] In line with this objective, the private company Bonifiche Ferraresi International (BFI) partnered with the Algerian government to cultivate 36,000 hectares of arid land to combat food insecurity. The project focuses on producing dried legumes (pulses), which will be entirely consumed domestically¾potentially reducing Algeria’s current 71.5% import dependency on these goods.[29][30]

Overall, by prioritizing local production and processing, the project appears to bolster Algeria’s food security and economic sovereignty rather than undermining it.[31] In addition to this balanced cooperation, the initiative also promises also promises technology transfer, seed provision, infrastructure development, and skills training for Algerians, although it is still too early to assess the extent to which these commitments will be fulfilled.

However, despite the absence of overt extractive agricultural practices, the project has not been without criticism. The NGO Crocevia has argued that BFI sidelined indigenous knowledge systems, which could have implications for the project’s long-term viability.[32] Due to limited publicly available data, it remains unclear whether these concerns are substantiated or whether BFI has conducted adequate due diligence.

In Kenya, a biofuels project has also raised concerns about potential agricultural extractivism. ENI is cultivating castor on 200,000 hectares of degraded agricultural land, refining it to produce biofuels. The project contributes to Kenya’s national biofuels strategy and aims to employ up to 400,000 farmers¾potentially improving Kenya’s national economic outlook.[33] Initial concerns that farmers would abandon food crops in favor of biofuels¾which would jeopardize national food production¾were addressed by the Kenyan government’s decision to allocate only degraded land, unsuitable for food crops.

However, the project is facing other challenges. Reports by Report[34] and T&E[35] show that some farmers lost money by cultivating castor. While ENI claims these were isolated incidents, growing evident suggests broader implementation issues.[36] More significantly, the project has yet to establish a full value chain in Kenya. Currently, castor is exported to Italy for refining. Although feasibility studies to construct a refinery in Kenya are underway, the current model removes value from Kenya and reproduces extractive patterns by exporting raw material. Resolving the issues with farmers and completing the value chain domestically will be crucial to ensuring that the project reflects the non-extractive principles the Mattei Plan seeks to uphold.

4. The Mattei Strategy in Italian Foreign Policy Doctrine: Break or Continuity?

The Meloni government places African policy at the center of its foreign policy priorities¾both continuing previous approaches and responding to multiple factors. This focus was notably announced as early as Giorgia Meloni’s inauguration speech in October 2022. One of the key ideas of the Mattei Plan, frequently reiterated during the Italy-Africa Conference on January 29, 2024, is that this policy should promote the development of African countries in order to create conditions that encourage people to choose not to migrate. The increase in migration flows, exacerbated by arrivals via the Sicily Channel since 2013, provides the immediate context for this policy, which is grounded in the traditional approach of fostering development to address migration at its source.[37]

While the extraction of hydrocarbons is the primary driver of the plan, other important aspects deserve attention. Italy positions itself as a more neutral actor than other European countries, due to its limited colonial past in Africa. This enables Italy to propose an African policy that, while traditional, is not burdened by the negative associations of colonialism. This positioning can also be read as a form of competition¾or even substitution¾vis-à-vis certain European countries with a more limited presence on the continent, reflecting a long-standing historical rivalry between Italy and France, often emphasized in Italian nationalist discourse.[38]

The "Mattei Plan" has evolved gradually. Initially a political statement lacking a clear programmatic framework, it has since developed into a government coordination tool, formalized by decree and officially launched at the January 2024 conference¾marking modest but notable progress. A European dimension has emerged, with Italy underscoring its intention to contribute to broader initiatives such as the Global Gateway. Another significant aspect is the high-level participation of African interlocutors—both from national government and multilateral organizations—who welcomed the initiative while stressing the importance of consultation.

For instance, Moussa Faki Mahamat, Chairperson of the African Union Commission, noted during the conference that Africans would have preferred earlier involvement, although remain open to collaboration with Italy and Europe.[39] This ambiguity in the Mattei Plan may in fact offer African partners an opportunity, as it helps avoid the imposition of predetermined solutions. Between the necessary Europeanization of the plan—emphasized notably by Italian President Sergio Mattarella, who advocates a multilateral approach—and the friendly African call for inclusion, a form of compromise is emerging.

Despite its national and nationalist origins, this initiative appears to be extending beyond its initial boundaries. One major challenge highlighted at the conference is Italy’s capacity to mobilize adequate resources: the country has pledged €5.5 billion¾a tangible but modest figure relative to actual needs. Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, reminded participants that the EU’s broader plan for Africa envisions €150 billion in investments, underscoring the scale of the challenge. The success of the Mattei Plan will thus depend on Italy’s ability to bring other actors and institutions on board.

Initially, the "Mattei Plan" was managed almost exclusively by the Prime Minister’s office. However, its further development requires broader involvement, notably from Italy’s diplomatic network and non-governmental actors engaged in Africa. A coordinated and inclusive approach is essential to mobilize all relevant stakeholders. Moreover, for the plan to be fully effective, it must be embedded within a broader European framework. The Rome conference on January 2024 marked a step in this direction, though it remains to be seen whether the Italian government and administration will succeed in fostering constructive synergies with European and international institutions.

Giorgia Meloni is often criticized for her tactical acumen, but also criticized for the limited reach of her power, which remains concentrated within a small circle that struggles to permeate the broader Italian institutional landscape. Her adoption of the "Mattei Plan" in 2022 can thus be seen as part of an effort to reinterpret national history, aligning this initiative with the ambitions of her government. The reaffirmation of national primacy, rooted in a realistic, state-centered vision, evolved in the lead-up to the January 2024 summit, gradually integrating Italian non-governmental actors as well as European and international institutions.

For Meloni, reinforcing Italy’s national position is a logical extension of her nationalist vision, paired with a European approach aimed at increasing the country’s influence on the global stage. However, this strongly national framework risks becoming a hindrance in multilateral processes, where cooperation and coordination¾particularly at sub-ministerial levels—are essential, especially within the integrated structures of the European Union.

Conclusion

For African actors interested in engaging with Italy, the political significance of the Mattei Plan cannot be overstated. It marks a shift from the erratic foreign policy approaches of the past, aiming instead to consolidate Italy’s diplomatic, economic, and institutional resources under a coherent international agenda. More than a development strategy, the Mattei Plan is a test of Italy’s capacity to sustain long-term international commitments and pursue a morally coherent yet pragmatic foreign policy. It represents Italy’s bid to position itself at the heart of Euro-African relations. Early indications suggest that Italy is gradually delivering on its premise of a non-predatory approach and expanding its presence across the continent. Elements such as debt restructuring, collaborative project design and a focus on sectors where Italy offers genuine expertise help reinforce the credibility of the Plan’s stated principles.

Nevertheless, certain initiatives¾such as the Lobito Corridor, limited local stakeholder consultation in Algeria, and incomplete value chains in Kenya¾expose vulnerabilities that could undermine its long-term credibility. Addressing these shortcomings will be essential to preserving the morally coherent vision Meloni aims to promote. In the same time, Regulatory clarity and institutional capacity are particularly crucial in the context of green and inclusive development, where fragmented or inconsistent rules undermine both investment incentives and development outcomes.[40] In this sense, the Mattei Plan’s challenge is to create a regulatory and governance architecture capable of translating investment flows into tangible and lasting benefits.[41] In absence of a clear governance framework, even well-funded initiatives risk duplication, inefficiency and limited impact on the ground.[42]

The true test for the Mattei Plan, however, may lie in its ability to move beyond a strictly European framework and integrate with broader, non-European initiatives. Strategic alignment with Morocco’s Atlantic Initiative could offer a key opportunity in this regard. By partnering with Morocco, Italy would reinforce regional cooperation and send a clear signal that European and African actors can genuinely co-create joint projects, rather than pursue parallel or competing agendas. Moreover, synergies with India’s IMEC on shared initiatives would further enhance Italy’s image as a credible and forward-looking actor in Africa and on the global stage. The ability of the Mattei Plan to seize such opportunities for transregional cooperation will be crucial to its long-term relevance and transformative potential.

Bibliography

AfroBarometer, ‘News Release Africa Day: Majority of Africans Say African Countries Should Be given Greater Influence in International Decision-Making Bodies’, 2025.

AICS, ‘Cresce la presenza AICS in Africa: attivate due nuovi Sedi in Costa d’Avorio e Uganda’, 2025, https://www.aics.gov.it/news/cresce-la-presenza-aics-in-africa-attivate-due-nuovi-sedi-in-costa-davorio-e-uganda/.

AICS, ‘Paesi prioritari’, 2023, https://www.aics.gov.it/paesi/paesi-prioritari/

AICS, ‘Sedi nel Mondo, Paesi di Competenza e Aree di Intervento’, Oltremare, n.d., https://www.aics.gov.it/oltremare/sedi-nel-mondo/.

Carbone et al., ‘Il Piano Mattei: Rilanciare l’Africa Policy Dell’Italia’; Carbone and Ragazzi, ‘Rebooting Italy’s Africa Policy’.

Consiglio Europeo Del 27 -28 Giugno, Le Comunicazioni Del Presidente Meloni Alla Camera Dei Deputati, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pPlk1tTymGU.

Dario Scannapieco and Marco Riccardo Rusconi, 'Piano Mattei -Audizioni, AICS e Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (Atto n 179)', 2024.

Diego Caballero Velez and Filippo Simonelli. Good Intentions in Need of Good Governance: The Unclear State of the Mattei Plan. Istituto Affari Internazionali. July 2025. https://www.iai.it/it/pubblicazioni/c05/good-intentions-need-good-governance-unclear-state-mattei-plan

Edmondo Cirelli, ‘Piano Mattei - Audizione - Vice Ministro Affari esteri Edmondo Cirielli (Atto n 179)’, 2024.

ENI, ‘2025 Capital Markets Update’, 2025, p. 36 https://www.eni.com/content/dam/enicom/documents/eng/investor/presentations/2025/2025-capital-markets-update/2025-capital-markets-update.pdf.

European Commission, ‘Aid, Development, Cooperation, Fundamental Rights’, accessed 18 June 2025, https://north-africa-middle-east-gulf.ec.europa.eu/countries_en.

Eurostat1, ‘Imports of Oil and Petroleum Products by Partner Country’, 2025, https://doi.org/10.2908/NRG_TI_OIL.

Eurostat2, ‘Imports of Natural Gas by Partner Country’, 2025, https://doi.org/10.2908/NRG_TI_GAS.

Fattibene and Manservisi, ‘The Mattei Plan for Africa’, p. 2.

FAO, ‘FAOSTAT Crops and Livestock Products’, FAOSTAT, 2025.

Federico Vecchioni, ‘Piano Mattei - Audizione - Bonifiche Ferraresi (Atto n 179)’, 2024.

Fonzo, ‘Enrico Mattei, il fondatore di ENI che sfidò le grandi compagnie petrolifere’, Geopop, 19 February 2024, https://www.geopop.it/enrico-mattei-biografia-vita-pensiero-incidente-morte/.

Giorgia Meloni, ‘Relazione Sullo Stato Di Attuazione Del Piano Mattei Aggiornata 10 Ottobre 2024’, Struttura di missione Piano Mattei, 2024.

Giovanni Carbone and Lucia Ragazzi, ‘Rebooting Italy’s Africa Policy’, ISPI, 2024, https://www.ispionline.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/policy-paper-ISPI-rebooting-Italys-africa-policy-2024_compressed.pdf.

Giovanni Carbone et al., ‘Il Piano Mattei: Rilanciare l’Africa Policy dell’Italia’, 2024; IOM, ‘Flow Monitoring Surveys with Migrants Arriving in Italy’, 2024, https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/DTM_Report_Flow%20Monitoring%20Surveys%20with%20migrants%20arriving%20in%20Italy_2023_1.pdf.

Istituto Poligrafico, ‘Decreto Legge 161’, pg. 3-4, 2023, https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legge:2023-11-15;161.

Jean-Pierre Darnis, Les relations entre la France et l’Italie et le renouvellement du jeu européen, L’Harmattan, 2021.

Jean Pierre Darnis. Le « plan Mattei » du gouvernement Meloni : vers une politique africaine pour l’Italie ? Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique. Note 05/24. February 2024. https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/notes/2024/202405.pdf

Kenya Ministry of Energy, ‘BIOENERGY STRATEGY 2020-2027’, 2020, https://www.energy.go.ke/sites/default/files/KAWI/Other%20Downloads/Bioenergy-strategy-final-16112020sm.pdf?.

Meloni, ‘Relazione Sullo Stato Di Attuazione Del Piano Mattei Aggiornata 10 Ottobre 2024’, p. 11.

Onorati, Piano Mattei per l’Africa per l’Italia?, 2024.

Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, ‘Vertice “The Mattei Plan for Africa and the Global Gateway”, le dichiarazioni alla stampa del Presidente Meloni’, 2025, www.governo.it, 2025b, https://www.governo.it/it/articolo/vertice-mattei-plan-africa-and-global-gateway-le-dichiarazioni-alla-stampa-del-presidente.

Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, ‘President Meloni Chairs Mattei Plan Steering Committee Meeting at Palazzo Chigi’, 2025a, https://www.governo.it/en/articolo/president-meloni-chairs-mattei-plan-steering-committee-meeting-palazzo-chigi/28768.

Report, ‘L’olio di Ricino’, 17 November 2024, https://www.raiplay.it/video/2024/11/Lolio-di-ricino---Report-17112024-bee3530e-3c1c-4878-aed4-f575cb7aac5d.html; T&E, ‘From Farm to Fuel: Inside Eni’s African Biofuels Gamble’, 3 June 2025, https://www.transportenvironment.org/articles/from-farm-to-fuel-inside-enis-african-biofuels-gamble.

Reuters, ‘Italy’s Eni to Invest $26 Billion in North Africa over next Four Years, CEO Says’, 8 April 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/italys-eni-invest-26-billion-north-africa-over-next-four-years-ceo-says-2025-04-08/.

Servizio Studi Senato and Servizio Studi Camera, ‘Schema Di DPCM Di Adozione Del Piano Strategico Italia-Africa: Piano Mattei’, Parlamento Italiano, 2024.

TheMaghrebTimes, ‘Algeria: Half a Million Hectares in the Sahara for Strategic Crops’, The Maghreb Times ! (blog), 4 July 2024, https://themaghrebtimes.com/algeria-half-a-million-hectares-in-the-sahara-for-strategic-crops/.

[1] Giovanni Carbone and Lucia Ragazzi, ‘Rebooting Italy’s Africa Policy’, ISPI, 2024,

https://www.ispionline.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/policy-paper-ISPI-rebooting-Italys-africa-policy-2024_compressed.pdf.

[2] Carbone and Ragazzi, ‘Rebooting Italy’s Africa Policy’, p. 48.

[3] Istituto Poligrafico, ‘Decreto Legge 161’, pg. 3-4, 2023,

https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legge:2023-11-15;161.

[4] Dario Scannapieco and Marco Riccardo Rusconi, Piano Mattei - Audizioni - (Atto n 179), 31 July 2024.

[5] Decreto Legge 161.

[6] Dario Scannapieco and Marco Riccardo Rusconi, Piano Mattei - Audizioni - (Atto n 179).

[7] Servizio Studi Senato and Servizio Studi Camera, ‘Schema Di DPCM Di Adozione Del Piano Strategico Italia-Africa: Piano Mattei’, Parlamento Italiano, 2024.

[8] Fonzo, ‘Enrico Mattei, il fondatore di ENI che sfidò le grandi compagnie petrolifere’, Geopop, 19 February 2024, https://www.geopop.it/enrico-mattei-biografia-vita-pensiero-incidente-morte/.

[9] ‘Vertice Italia-Africa, Meloni’.

[10] Fattibene and Manservisi, ‘The Mattei Plan for Africa’, p. 2.

[11] Giorgia Meloni, ‘Relazione Sullo Stato Di Attuazione Del Piano Mattei Aggiornata 10 Ottobre 2024’, Struttura di missione Piano Mattei, 2024.

[12] AICS, ‘Paesi prioritari’, 2023, https://www.aics.gov.it/paesi/paesi-prioritari/.

[13] AICS, ‘Cresce la presenza AICS in Africa: attivate due nuovi Sedi in Costa d’Avorio e Uganda’, 2025, https://www.aics.gov.it/news/cresce-la-presenza-aics-in-africa-attivate-due-nuovi-sedi-in-costa-davorio-e-uganda/.

[14] European Commission, ‘Aid, Development, Cooperation, Fundamental Rights’, accessed 18 June 2025, https://north-africa-middle-east-gulf.ec.europa.eu/countries_en.

[15] AfroBarometer, ‘News Release Africa Day: Majority of Africans Say African Countries Should Be given Greater Influence in International Decision-Making Bodies’, 2025.

[16] Carbone et al., ‘Il Piano Mattei: Rilanciare l’Africa Policy Dell’Italia’; Carbone and Ragazzi, ‘Rebooting Italy’s Africa Policy’.

[17] Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, ‘President Meloni Chairs Mattei Plan Steering Committee Meeting at Palazzo Chigi’,2025a, https://www.governo.it/en/articolo/president-meloni-chairs-mattei-plan-steering-committee-meeting-palazzo-chigi/28768.

[18] Edmondo Cirelli, ‘Piano Mattei - Audizione - Vice Ministro Affari esteri Edmondo Cirielli (Atto n 179)’, 2024.

[19] Consiglio Europeo Del 27 -28 Giugno, Le Comunicazioni Del Presidente Meloni Alla Camera Dei Deputati, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pPlk1tTymGU.

[20] Giovanni Carbone et al., ‘Il Piano Mattei: Rilanciare l’Africa Policy dell’Italia’, 2024; IOM, ‘Flow Monitoring Surveys with Migrants Arriving in Italy’, 2024, https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/DTM_Report_Flow%20Monitoring%20Surveys%20with%20migrants%20arriving%20in%20Italy_2023_1.pdf.

[21] ENI, ‘2025 Capital Markets Update’, 2025, p. 36 https://www.eni.com/content/dam/enicom/documents/eng/investor/presentations/2025/2025-capital-markets-update/2025-capital-markets-update.pdf.

[22] AICS, ‘Sedi nel Mondo, Paesi di Competenza e Aree di Intervento’, Oltremare, n.d., https://www.aics.gov.it/oltremare/sedi-nel-mondo/.

[23] Eurostat1, ‘Imports of Oil and Petroleum Products by Partner Country’, 2025, https://doi.org/10.2908/NRG_TI_OIL.

[24] Eurostat2, ‘Imports of Natural Gas by Partner Country’, 2025, https://doi.org/10.2908/NRG_TI_GAS.

[25] Reuters, ‘Italy’s Eni to Invest $26 Billion in North Africa over next Four Years, CEO Says’, 8 April 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/italys-eni-invest-26-billion-north-africa-over-next-four-years-ceo-says-2025-04-08/.

[26] Dario Scannapieco and Marco Riccardo Rusconi, 'Piano Mattei -Audizioni, AICS e Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (Atto n 179)', 2024.

[27] ibid.

[28] The Maghreb Times, ‘Algeria: Half a Million Hectares in the Sahara for Strategic Crops’, The Maghreb Times ! (blog), 4 July 2024, https://themaghrebtimes.com/algeria-half-a-million-hectares-in-the-sahara-for-strategic-crops/.

[29] Federico Vecchioni, ‘Piano Mattei - Audizione - Bonifiche Ferraresi (Atto n 179)’, 2024.

[30]FAO, ‘FAOSTAT Crops and Livestock Products’, FAOSTAT, 2025.

[31] Meloni, ‘Relazione Sullo Stato Di Attuazione Del Piano Mattei Aggiornata 10 Ottobre 2024’, p. 11.

[32] Onorati, Piano Mattei per l’Africa per l’Italia?, 2024.

[33] Kenya Ministry of Energy, ‘BIOENERGY STRATEGY 2020-2027’, 2020, https://www.energy.go.ke/sites/default/files/KAWI/Other%20Downloads/Bioenergy-strategy-final-16112020sm.pdf?.

[34] Report is the most important investigative journalism program in Italy.

[35] T&E is a leading European NGO promoting sustainable transport policies

[36] Report, ‘L’olio di Ricino’, 17 November 2024, https://www.raiplay.it/video/2024/11/Lolio-di-ricino---Report-17112024-bee3530e-3c1c-4878-aed4-f575cb7aac5d.html; T&E, ‘From Farm to Fuel: Inside Eni’s African Biofuels Gamble’, 3 June 2025, https://www.transportenvironment.org/articles/from-farm-to-fuel-inside-enis-african-biofuels-gamble.

[37] Jean Pierre Darnis. Le « plan Mattei » du gouvernement Meloni : vers une politique africaine pour l’Italie ? Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique. Note 05/24. February 2024. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/notes/2024/202405.pdf

[38] Jean-Pierre Darnis, Les relations entre la France et l’Italie et le renouvellement du jeu européen, L’Harmattan, 2021.

[39] Jean Pierre Darnis. Le « plan Mattei » du gouvernement Meloni : vers une politique africaine pour l’Italie ? Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique. Note 05/24. February 2024. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.frstrategie.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/notes/2024/202405.pdf

[40] Diego Caballero Velez and Filippo Simonelli. Good Intentions in Need of Good Governance: The Unclear State of the Mattei Plan. Istituto Affari Internazionali. July 2025. https://www.iai.it/it/pubblicazioni/c05/good-intentions-need-good-governance-unclear-state-mattei-plan

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.