Publications /

Opinion

In 2010, when I was one of the vice presidents at the World Bank, colleagues I and published a very upbeat book about the possibility of emerging and developing economies replacing advanced countries as engines of global economic growth. While the latter would be grappling with the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the former, already growing at a faster pace in the previous decade and accounting for more than half of the annual increases in global GDP, had largely shown an appetite for carrying out structural reforms needed to converge with the richest.

In the years that followed, I was forced to temper that optimism. The exuberant Chinese growth had been fundamental for the dynamism of other non-developed countries, and the Chinese route had become one of lower speed. Additionally, the economic rise of many of the big emerging markets had given rise to a certain arrogance and complacency about continuing to reform – this applies well to Brazil, Russia, South Africa, Turkey, and many others.

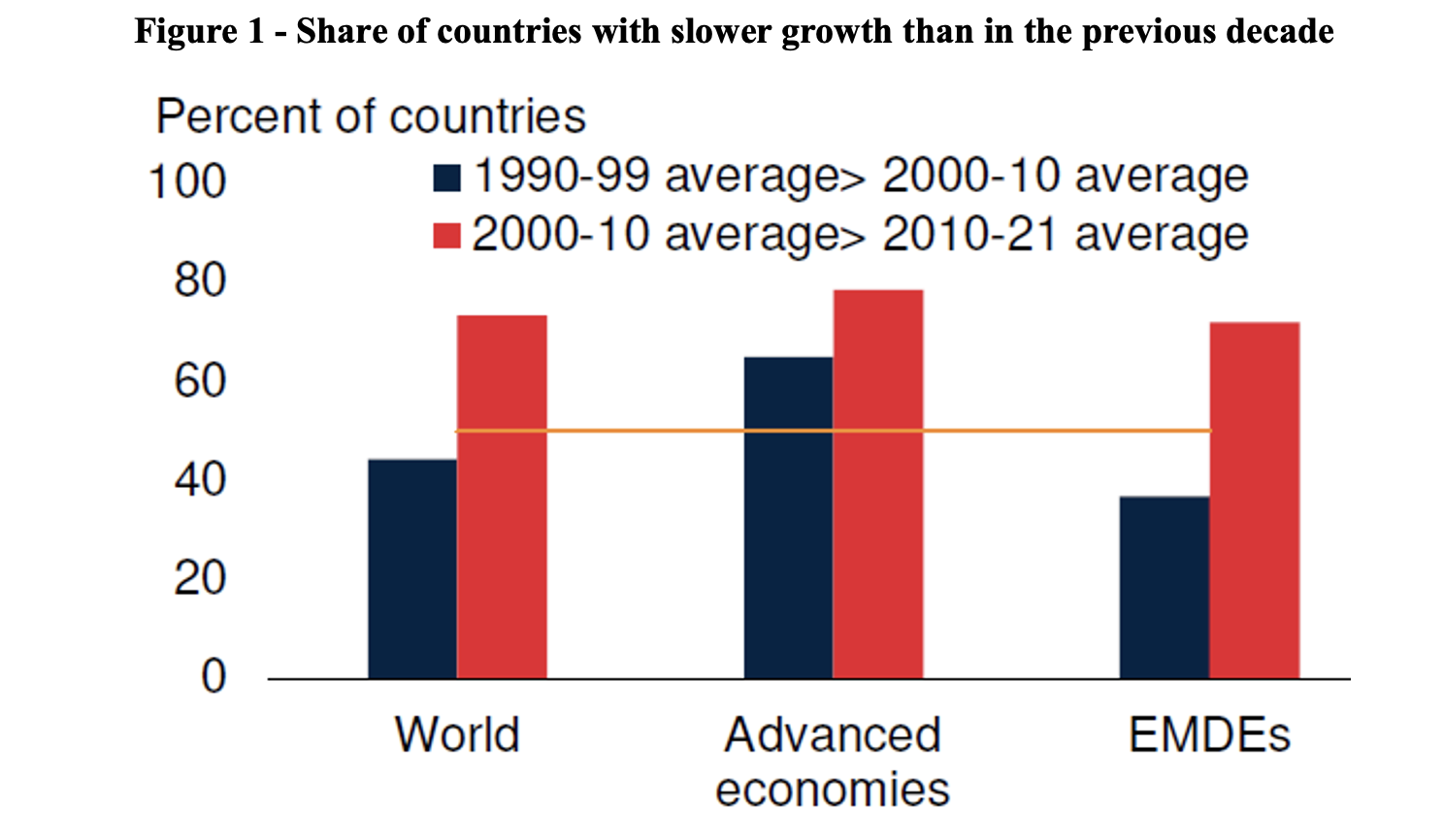

The low growth of the richer economies ended up dragging down the performance of the others. The slowdown was widespread: in 80% of advanced economies and 75% of emerging and developing economies, average annual growth was lower in 2011-21 than in 2000-10 (Figure 1)

Source: Kose and Ohnsorge (2023)

Last week the World Bank released a study - Falling Long-Term Growth Prospects - projecting a reduction in the speed limit at which the global economy can grow over the remainder of this decade. The economic factors that have propelled prosperity over the past three decades are reportedly losing their grip.

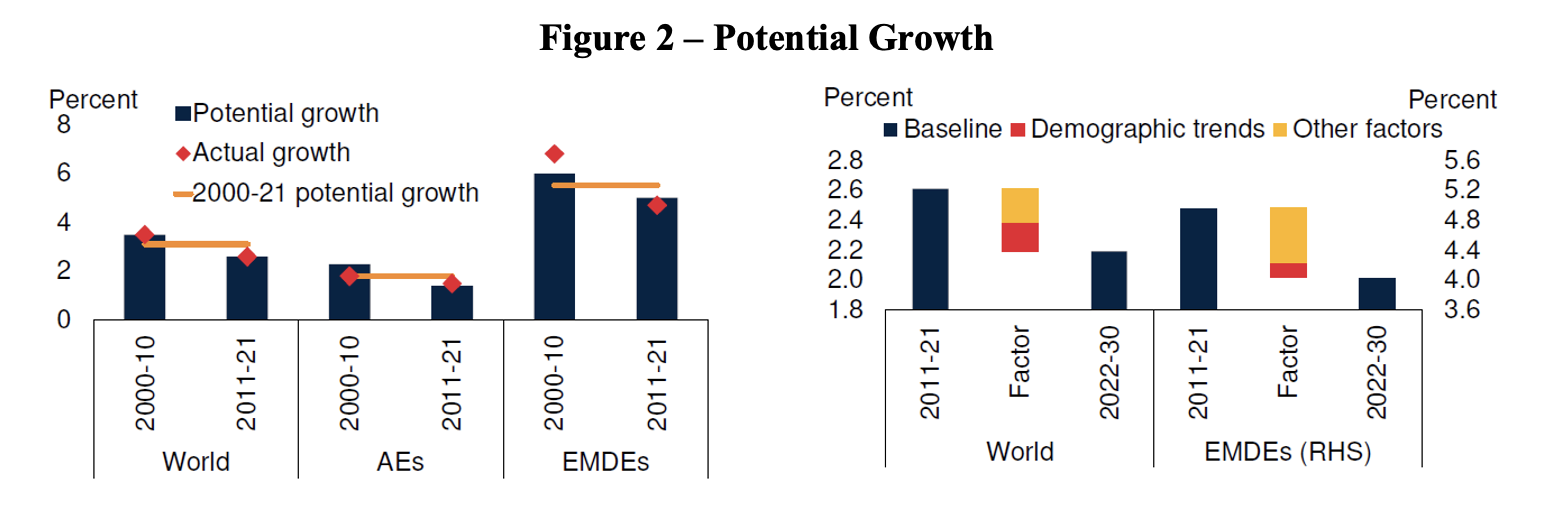

Between 2022 and 2030, the report projects a decrease to 2.2% per year in average potential global GDP growth - that is, without triggering inflation - which corresponds to about a rate a third lower than that prevailing. in the first decade of this century. The fall on the side of developing economies, including China, would be equally sharp: from 6% per year between 2000 and 2010 to 4% per year for the remainder of this decade (Figure 2).

Source: Kose and Ohnsorge (2023)

It is not just a question of the consequences of the series of shocks to the global economy over the last three years, such as the pandemic, the invasion of Ukraine, the greater frequency and intensity of adverse weather phenomena, and the acceleration of inflation. The sharp rise in inflation over the past two years has led to the tightest global monetary policy tightening in four decades.

Fiscal policy also became less supportive following the significant deterioration in public budget balances during the 2020 global recession, when debt levels reached historic highs. Amidst these multiple adverse shocks, in the last three years, the global economy has experienced the biggest growth slowdown following a global recession. The picture could worsen if the ongoing monetary tightening unfolds into financial crises, which tend to be digested with lower subsequent economic growth.

However, all the fundamental factors of GDP growth have already been slowing down in the last decade. China has been moving towards a slower pace of economic expansion. But fundamentally, improvements in human capital, labor force growth, investment (including because of political uncertainty) and total factor productivity (including through the reallocation of production factors across sectors) have slowed their pace, as shown by the World Bank report. These growth engines are expected to continue losing steam for the remainder of the decade.

The aging and slow growth of the global workforce are highlighted as downward factors, explaining half of the expected slowdown in potential GDP growth through 2030 (Figure 2). Lower levels of participation in the labor force, as societies age, will have fiscal consequences via social security, in addition, of course, to lower average productivity per inhabitant.

Furthermore, international trade growth is much weaker now than in the early 2000s. The prospect of “deglobalization”, even if partial and relative, tends to bring higher costs than the gains realized in globalization.

What should countries do in the face of this prospect of a “lost decade”? Above all, adhere to macroeconomic and financial policies that mitigate the ups and downs of economic cycles: controlling inflation, guaranteeing the stability of the financial sector, reducing very high debt levels, and restoring fiscal prudence. Such policies can help countries attract investment by bolstering investor confidence in national institutions and domestic policymaking.

This must be done consistently with increased investment in areas such as transport and energy, climate-smart agriculture, and manufacturing, as well as land and water systems. The report estimates that sound investments aligned with key climate targets can increase potential growth by up to 0.3 percentage points per year and strengthen the future resilience to natural disasters.

Reducing still high and unnecessary trade costs remains an important item on the agenda. Countries with the highest transport and logistics costs could cut their trading costs in half by adopting trade facilitation and other practices from countries where such costs are low. Trade costs, moreover, can be lowered in a climate-friendly way by removing the biases that exist in favor of carbon-intensive goods in tariff walls of many countries and by removing restrictions on access to green goods and services.

Exploring the service sector as a new engine of economic growth also applies. To give you an idea, according to the report, digitally delivered professional services exports have risen to over 50% of total service exports in 2021, up from 40% in 2019. Better service delivery is also a source of substantial productivity gains.

Finally, there is what can be done to raise labor force participation rates. The report highlights how, in some regions, such as South Asia, he Middle East, and North Africa, an increase in female workforce participation rates for the average of all emerging markets and developing economies could accelerate their potential GDP growth of up to 1.2 percentage points per year between 2022 and 2030. The case of Morocco has been recently approached here.

One last call is the hardest to obtain: restoring the international economic integration that has been instrumental in leveraging global prosperity for over two decades since the 1990s!