Publications /

Opinion

Background

The African Union in 2018 agreed to implement the world’s second-largest free-trade area measured by number of countries, people, and geographical size, with the signing of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). This agreement will ultimately lead to a continent-wide free trade area consisting of 54 countries with 1.3 billion people and a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion[1]. This equates to about 19%-20% of the GDP of the European Union and China, which are $17 trillion and $18 trillion respectively, as of 2021. Africa accounts for roughly 3% of global gross domestic product output[2]. With 17% of the world’s population, a growing middle class with improved access to technology, and an underserved market, Africa is believed to be the next frontier of growth for global trade and geopolitical influence.

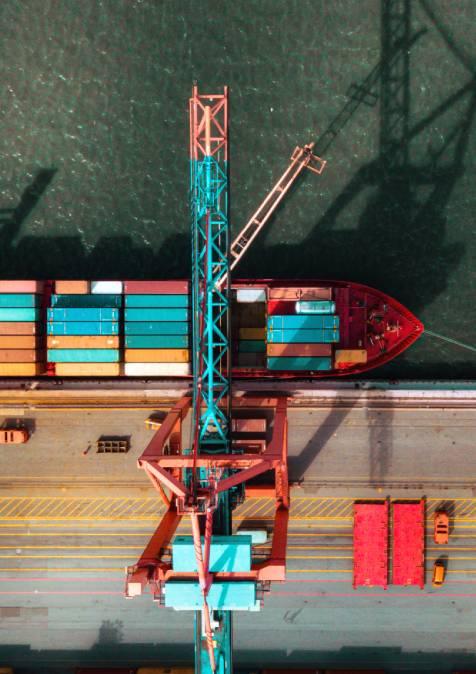

AfCFTA aims to accelerate intra-African trade and enhance Africa’s trading position in global value chains. Among member states, it is expected to reduce tariffs, remove technical barriers, and ensure trade policy and regulation standardization. For its external partners, the implementation of AfCFTA will provide markets at scale, make investments not only viable but attractive. A World Bank report suggests Africa will see an increase in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) of between 111% to 159% by 2035 under AfCFTA, mainly driven by private-sector investment [3]. According to this report, Europe is expected to lead the pack on FDI in Africa, followed by Asia, North America, and South America. FDI to African countries hit a record $83 billion in 2021, up from 4.1% in 2020 to 5.2% of global investments[4]. African governments are reviewing and implementing policies and programmes to position their economies as the best places to invest. They are improving the ease of doing business, and creating incentives for foreign companies, particularly those in the manufacturing and transportation sectors.

For example, in 2019 Ghana launched its Automotive Development Policy, aimed at positioning the country as the automotive hub of West Africa by offering a 10-year tax break to the automotive manufacturing industry. This appears to have already attracted a significant number of key original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) from the EU and Asia. The African market is a key consideration for most of these automobile companies. Toyota wants to generate 30% of its total annual sales revenue, currently at $60 billion, from Africa over the next two decades[5].

The European Union and China in particular seek to gain influence in Africa through provision of development aid. For China, Africa is an important component of its global strategy built on the economic and political model of state capitalism and authoritarianism as the means to achieve prosperity and global power status. The EU on the other hand has traditionally engaged Africa through development policies aimed at promoting European values and enhancing the European Union as a normative power. Both China and the EU have interests in ensuring the successful implementation of the agreement creating the African Continental Free Trade Area.

China's Involvement

The Chinese government has also been deeply involved with the AfCFTA. China provides capacity-building support for the secretariat, and major infrastructure investments across Africa within the framework of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Dakar Action Plan (2022-2024). In 2021, the AfCFTA secretariat and China’s Ministry of Commerce signed a memorandum of understanding to establish an expert group to collaborate and share experiences on intellectual property rights, customs procedures, digital trade, and competition policy, and to exchange concepts and progress on institutional capacity and implementation of AfCFTA [6]

China’s contemporary engagement in Africa is rooted in the anti-colonial struggle. During this time, the focus was building geopolitical and ideological solidarity to promote collectivist societal models. However, this has evolved over the decades. In 2006, China published its first Africa policy document, aimed at building a new type of strategic partnership with Africa based on political equality and mutual trust, economic win-win cooperation, and cultural exchange[7]. The second policy document was published in 2015 in the lead-up to the second FOCAC Summit in South Africa. This policy sought to further clarify China's determination to develop relations with Africa and expound the new vision[8].

More recently the China-Africa Cooperation Vision 2035 has outlined the medium- and long-term areas and objectives of cooperation. Within this framework, initiatives including the Action Plan for Boosting Intra-African Trade (BIAT), and closer Belt and Road partnership between China and Africa, among others, will be pursued. China’s growing market shares and technological innovations have had implications for international technical standardization, leading to the risk of bifurcation of standards and value chains. Having undergone standardization reform, shifting from a state-controlled approach to a state-centric approach[9], China is exporting its standardization approach[10]. This can be observed in the massive project it is carrying out across Africa.

The European Union's Response

The European Union's policy on Africa in recent times appears to be driven by the need to react to China’s exploits in the context of perceived strategic competition[11]. To this end, Europe is stimulating investments to drive the green transition and digital transformation, the development of major infrastructure, and job creation[12]. Countries within the European Union are also pursuing initiatives to counter China’s growing influence. France in 2019, for example, approved a bill to increase the aid budget to 0.55% of GDP by 2022 to counter China [13], though this level is still below the 0.7% ODA target set by the European Union [14]. The Choose Africa initiative was also launched by the French Government, with €2.5 billion earmarked to finance and support African start-ups, microenterprises, and SMEs. In 2021, the EU launched the Global Gateway initiative to represent a European counter to China’s Belts and Road Initiative, as part of the EU’s strategy for a new deal with Africa.

The European Union is pursuing influence in Africa in line with its Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027, and the Neighborhood, Development Cooperation and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI). Of the €79.5 billion available from the NDICI, 37% has been dedicated to sub-Saharan Africa to contribute to eradicating poverty and promoting sustainable development, prosperity, peace, and stability. Beyond this, the EU also aims to establish a more equitable and balanced relationship with Africa with the emergence of the African Continental Free Trade Area, by promoting trade and supporting SMEs[15].

The European Union continues to make significant contributions to the successful implementation of the AfCFTA by providing political, financial, technical, and policy support. Over €74 million was pushed into supporting the AfCFTA from 2014 to 2020 through the Pan-African Programme. This funding helped with capacity building for the negotiation, ratification, and implementation of the Agreement[16]. The EU has also been providing technical support to African governments. In response to China’s state-centric approach to technical standardization, the EU and the US formed the Trade and Technology Council to foster cooperation on trade and technology-related issues.

The State of Play: China and the European Union

China’s annual FDI flows into Africa have seen significant growth over the years. The China Africa Research Initiative estimated Chinese FDI at $4.2 billion in 2020, up from $75 million in 2003. A report by the Swiss African Business Circle estimated that China directed on average 27% of its investments in Africa over the past decade. Investments in Africa can be viewed in terms of projects, jobs created, and capital. From 2014 to 2018, China accounted for the largest share of jobs created and capital inflows to Africa[17]. In this same period, the United States and France were the largest investors when it came to projects, followed by the United Kingdom and China. As of 2021, UNCTAD figures indicate that European investors remain the largest holders of foreign assets in Africa, led by the United Kingdom ($65 billion) and France ($60 billion)[18]. Pre-Brexit EU investment stocks amounted to €261 billion, representing 40% of FDI in Africa[19]. With the United Kingdom’s exit, the EU has been dealt a big blow. France is now the EU’s largest investor in Africa, albeit with no stock increases since 2013[20]. China became Africa’s biggest bilateral trading partner in 2021, with Chinese-African trade reaching $254 billion[21]. According to the General Administration of Customs of China, exports to Africa are up 35.3% year-on-year, while imports are up 43.7% year-on-year[22]. The General Administration of Customs of China estimates the total bilateral trade between China and Africa in 2021 to be $254.3 billion, of which Africa exported $105.9 billion of goods to China.

As the competition between the EU and China for influence and market share in Africa increases, China appears to be winning the hearts and minds of the people. An Afrobarometer survey in 34 African countries between 2019 and 2021 revealed that China was perceived positively by Africans for its assistance and influence on the continent, although this positive perception has been waning over the past five years. There are public concerns over bad labor practices and environmental degradation. In Ghana, for example, a $2 billion bauxite-for-infrastructure deal with Chinese state-owned firm Sinohydro Corp attracted massive public protest for the threat it poses to the environment and people[23]. Nonetheless, China enjoys goodwill from African governments. In June 2020, for example, 25 African countries backed Beijing in a United Nation vote about the Hong Kong national security law[24].

Power is shifting towards Asia as Africa diversifies its trading partners. China is emerging as a preferred partner because it appears not to impose conditionalities or push lopsided agreements, while it possesses an appreciation of African values. Africans perceive China as offering better conditions for investment, giving it positive reviews at 70.6%, against the EU’s 69.8%. China also scored high on ‘Non-interference in internal affairs’, with 68.1% against the EU’s 57.5%[25].

A significant amount of funds has been invested so far by the Chinese in building infrastructure in Africa, mainly roads, railways, factories, and ports. Most African governments see China’s record of fast and successful economic growth as a model that offers valuable lessons. Despite its gains, China remains second to the United States as the preferred development model for Africans. The EU, on the other hand, appears to be struggling with negative public reviews. The Global Attitude survey by Pew Research Centre shows that public opinion among Africans does not put the EU forward as a better development partner[26]. The bloc’s influence in Africa is waning due to growing mistrust. For Africa, the mistrust derives from perceived double standards in dealing with issues such as refugees and migration, meeting development assistance and climate change financing commitments, and thriftiness in sharing technology[27]. There is also the remnant of Europe’s colonial and post-colonial past—baggage China does not carry.

Turning the Tide for the EU

The shifting geopolitical paradigm in Africa as a result of China’s exploits and its accelerated growth in influence has implications for the Europe-Africa relationship. The EU’s relationship with Africa must evolve in light of these current dynamics. Europe must address its past with the African Continent and must be considerate of the needs of the African people. From the 2022 European Union-Africa Summit, there are indications of these elements being factored into the EU plan’s for Africa. In re-imagining its relationship with Africa, the EU must realign its plans on investment, trade, and social acceptance. Africa is not looking to drive its growth with only one partner. Governments on the Continent are keen on fostering multi-partner relationships. It is therefore important for Europe to desist from seeing Africans as spectators in their own development, and to actively engage the continent in drafting shared visions. The EU’s policy on Africa should be driven by economic growth and industrialization of the continent.

The AfCFTA allows member states to enter into other free trade agreements with countries outside Africa. In leveraging this, the European Union must review the Economic Partnership Agreement (the status of which can be found here) to ensure it is equitable and considerate of the growing needs of industries on both continents. The European Union’s new strategy for Africa must incorporate projects that help build trust at all levels of the social structure. Within the Simplified Trade Regime framework under AfCFTA, initiatives that enable micro, small, and medium enterprises to reap the benefits that come with the single market must be ensured.

Beyond promoting the Global Gateway as the EU’s instrument to match China’s massive investment in Africa, among other things, it should be used as a tool for capacity building, knowledge, and technological transfer. The European Union must continue with its commitment to the successful implementation of the AfCFTA

Though they differ in their approaches, many of the goals that the European Union and China seek to achieve with their policies towards Africa are similar in many aspects. However, there is little or no collaboration on Africa between these two actors. Africa should steer the development of a trilateral relationship with both the European Union and China, based on mutually agreed objectives to promote balance and harmonized development.

Author is a Research Fellow with Human Security Research Centre Ghana and an Alumnus of the 2017 Atlantic Dialogues Emerging Leaders Program.