Publications /

Policy Brief

The recent elections to the African Union (AU) were unfavorable for Morocco, which lost out to Algeria for the post of Vice-President of the Union and was not re-elected to the Peace and Security Council (PSC). This result was met with incomprehension and a sense of failure on the part of Moroccan diplomacy. However, the article proposes to go beyond this emotional vision to analyze the mechanisms of influence within the AU. The Moroccan candidacy evolves in an institutional environment marked by power struggles and a need for balance. By seeking to maintain a position of leadership, Morocco has exposed itself to significant electoral risks. The article invites us to draw lessons from this situation in order to better understand and anticipate institutional political dynamics.

Recent elections to the African Union (AU) proved unfavorable for Rabat. Morocco’s candidate lost out to Algeria in the election for the post of Vice-President of the African Union. Similarly, Morocco’s candidate was not re-elected to the Peace and Security Council (PSC). The seat could revert to Algeria at the extraordinary session on April 15, 2025, unless the politically fragile Libyan contender, backed by Morocco, manages to secure the requisite two-thirds of votes.

This outcome has provoked incomprehension and rejection, and is perceived as a notable failure for Moroccan diplomacy, and even a setback for its institutional positioning within the AU. Beyond this legitimate—but somewhat emotional—feeling, it is essential to see this setback as an opportunity for learning, reflection, and self-criticism.

The approach we adopt here focuses less on the subjective aspects of the defeat and more on the rules of the game of influence within the AU and their impact on the Moroccan bid. The aim is to highlight the elements that can help us understand the environment in which the Moroccan bid is being made. Tension, undue influence on the vote, blackmail: all these terms certainly partly reflect reality, but they only partly translate the AU's operating logic. In this way, we will be able to shed objective light on the pitfalls to be avoided and the levers of influence to be used, both in the long-term and in the more immediate context of the consequences of the results of the Commission elections for Morocco's African strategy.

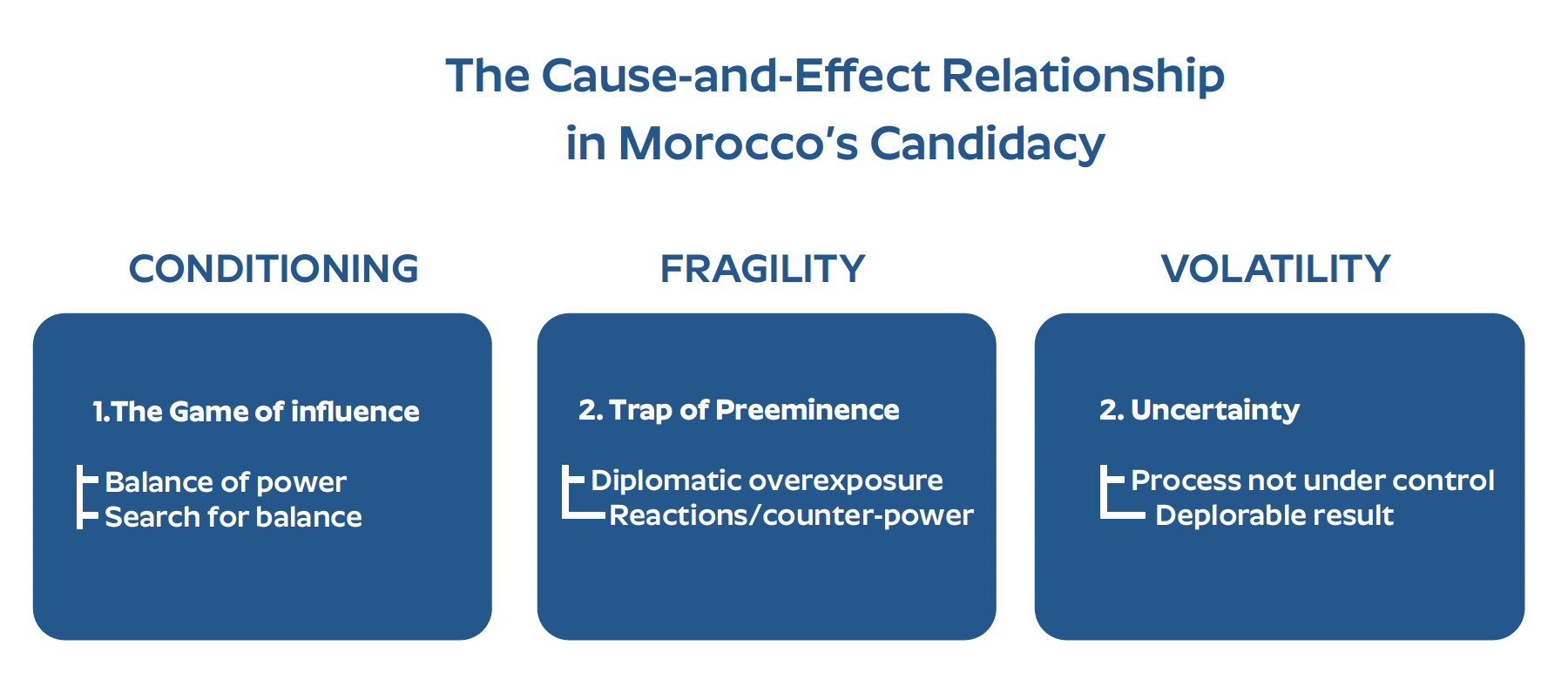

In this article, we argue that the Moroccan candidacy has evolved in an institutional geopolitical environment paradoxically marked by power relations and the quest for balance (I). It has advanced at a steady pace, almost unconsciously, towards the ‘pre-eminence trap’, in which any overexposure becomes counterproductive (II).This trajectory has ultimately projected it into an electoral dynamic fraught with uncertainty, and therefore high risk (III).

AU: A Constant Interplay Between Power and Institutional Balance

Fundamental knowledge of what is happening in the AU is essential to better understand the complexity of the issues at stake in the Commission elections[1]. Interpersonal and subjective factors interact with the structural and functional dynamics of the Organization, resulting in a complex, variable-geometry competition.

The representations of the players and the logics that guide their actions provide the relevant terrain for identifying this complexity. In this institutional space, the dynamics of the quest for power—that of the African powers (South Africa, Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Morocco and Nigeria, the G6)—intersect with the trajectories of other states in search of an alternative counterweight. For the G6, the challenge is to maintain a dominant influence, due in particular to their historical roles, their diplomatic and financial clout, and their ability to organize alliances and take initiatives. The resulting power play generates a competition for influence, creating strong contradictions and polarization, sometimes exacerbated during Commission elections. Other countries oscillate between recognition and mistrust of the G6’s clout. Some take advantage, while others seek to rebalance their influence on the continent.

Of course, what gives life to the organization is this quest for influence, the tensions it creates between different representations, and the conflicts it provokes. The quest for influence is like a zero-sum game, particularly during political events or institutional high points, as illustrated by the most recent Commission elections. The election of the Algerian candidate and the non-renewal of Morocco’s mandate on the PSC are seen by Rabat as a strategic defeat, undermining its influence within the AU. This situation is reminiscent of Algiers’s reaction to Morocco’s previous election and re-election to the PSC, a setback that Algeria saw as a weakening of its own diplomatic position.

The implications of this competitive dynamic, in which the winner-takes-all rule amplifies tensions in an institutional space already weakened by geopolitical rivalries—as is the case between Morocco and Algeria—are becoming clearer. More broadly, it reveals the paradox of the AU, in which cooperation and conflict constantly coexist. Member states, while seeking to assert themselves, must juggle, not without difficulty, the need to collaborate with the temptation to increase their power at the expense of other states. This reality stems from the fact that power lies in the hands of states, so that the structures of the international organization draw their strength or weakness from states. Moussa Faki Mahamat, ex-Chairman of the AU Commission (AUC), stated that “the excessive exercise of their sovereignty (states) hinders the transfer of powers to the Commission. The strength of the AU, as a grouping of African countries, lies in the power that member states give it to implement their decisions[2]”.

The environment in which Moroccan diplomacy is being deployed can be considered particularly tense, because certain factors are challenging the success of its initiatives. Morocco's proposals come up against opposition from countries including Algeria and South Africa, backed by their auxiliaries Namibia, Lesotho, and Zimbabwe. In 2025, the elections to the Union Commission for the positions of President, Vice-President, and North African representative on the PSC, will highlight a highly competitive power game and a context of high volatility. A political and diplomatic rationality is emerging, oscillating between greed and ideology, but focused on the national interest.

This zero-sum game dynamic establishes two parameters between which a country of Morocco’s stature moves: on the one hand, it must preserve its interests, status, and role in the face of the strategies of other G6 members; on the other hand, it must avoid diplomatic overexposure that would be likely to engender distrust or mistrust among smaller states. The challenge is to maintain a strong position and influence without appearing dominant. However, observation of the power game within the AU reveals that, in practice, maintaining this position over the long term is complicated. There is a cause-and-effect relationship between a player's desire to dominate and the need for sharing of power. In other words, the more a state reinforces its influence and inspires its institutions, the more it stirs up mistrust and counter-power effects. Several examples illustrate this situation, when the expansion of a state’s influence has provoked resistance, particularly during the Commission’s election periods:

- The election of Morocco to the PSC in 2018 and then in 2022 was achieved despite initiatives by Algeria and South Africa to block its candidacy. The majority of member states wanted to oppose the Algerian domination of the PSC and the Commission's Peace and Security Department;

- Nigeria’s de-facto permanent seat on the PSC since the 2002 Gentlemen's Agreement has been the subject of constant criticism from West African countries. In 2022, an initiative was launched to end Nigeria’s privilege, but without success.

More recently, the same reasoning somehow prevailed when the former Kenyan head of government, Raila Odinga, stood for election to the presidency of the Commission. His failure in this election was due to the fact that many heads of state wanted to counter his candidacy, considering that his high political status could create a permanent power struggle between the future Commission and the states.

A similar logic has prevailed in Morocco’s case, causing it to lose the post of vice-president and its seat on the PSC.

How does Morocco's loss of the vice-president and PSC member positions illustrate the consequences of the quest for power and the pre-eminence trap?

The Trap of Diplomatic Preeminence

Morocco has succeeded in elevating itself to the status of an influential country during its eight-year presence, joining South Africa, Algeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, and Nigeria. However, Moroccan diplomacy needs a more perceptible return on investment from its successes and actions. What can be described as ‘achievements to be strengthened’ stem from a triple dynamic of influence.

Influence of position

On the one hand, this is demonstrated by Morocco’s dynamism within the PSC, as shown by its two successful elections since its return to the institution, demonstrating both the existence of a mark of confidence and continuous diplomatic rallying. In addition, the first procedures manual was adopted in 2019 in Skhirat thanks to a strong will to institutionalize working methods. In addition, a major strategic advance was made with the approval of Decision 693[3], which reserves management of the Sahara issue to a troika of heads of state. This decision marks a radical departure from the AU’s previous stance, which was demonstrated by opinions and decisions that were generally unfriendly to Morocco.

On the other hand, the establishment of the African Migration Observatory in Morocco is a highly significant milestone in terms of its institutional position. It helps to forge the status of His Majesty King Mohammed VI as an African leader on migration issues. This recognition by his peers gives him full legitimacy, conferring on him the title of ‘African Champion of Migration’[4].

Despite major challenges, Morocco is establishing itself gradually in the realm of functional positioning. This is the case for the post of Director General of the Commission, propelling Ambassador Fathallah Sijilmassi to the rank of third key figure within the institution.

Behavioral influence

Three factors illustrate the influence exerted through the desire to carry out innovative and convincing actions focused on:

- The promotion of democratic values in Africa through structuring initiatives, notably the organization, in Rabat, of an annual training session for hundreds of election observers and a Dialogue Seminar on Elections and Democracy in Africa. The third dialogue was held in April 2025;

- Active engagement in the institutional and financial reform of the African Union Commission, contributing to efficiency and governance improvements;

- The exploration of new peace and security themes, notably through the integrated approach of the Peace-Security-Development (PSD) nexus. This dynamic was concretized by the organization, in Tangier, of the first AU Conference on the PSD nexus, the final declaration from which was endorsed by the heads of state, affirming the continent's commitment to this innovative approach.

Influence by expertise

This area is expanding considerably, with the mobilization of Moroccan experts in a variety of strategic fields, ranging from the review of AU policies to capacity building for African states, and knowledge production and participation in high-level consultative bodies. This includes participation in the revision of the AU’s policy framework on post-conflict reconstruction and development[5], as well as the first AU journal on post-conflict studies, published by the Department of Peace and Security[6].

Morocco’s influence is also reflected in its support for the efforts of the Department of Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), through the deployment of diplomats, technicians, and military personnel, thus actively participating in the implementation of the mandate of this strategic department.

In addition, the Policy Center for the New South’s (PCNS) membership of the African Network of Think Tanks for Peace (NeTT4Peace) is a welcome development for Morocco. This initiative by the PAPS department aims to promote the essential strategic partnership between the research community (focused on governance, peace, and security) and the department[7].

Proud of its achievements and confident in its gains, Morocco ultimately failed to secure the post of Vice-Chairman and a renewed mandate on the PSC, highlighting the unforeseen challenges it faces on the African scene. An analysis of the voting process shows that, in the first round, the two candidates were tied, each gaining 21 votes, while the Egyptian candidate received only six. From the second round onwards, a trend began to emerge, with votes switching in favor of the Algerian candidate. In the seventh round, she remained the only candidate, having received 33 votes. The Moroccan candidate, meanwhile, was eliminated in the sixth round, and the Egyptian candidate much earlier, in the third round. Thus 12 countries made their choices in the final moments of the process, no doubt under the influence of promises of reward!

In any case, it seems essential to focus on objective factors and verifiable indices, rightly setting the cursor at the beginning of the process. For what is decisive for Morocco is not so much the switches of votes at the end of the process, but rather to emphasize that, despite its loss of influence in Africa since Morocco’s return to the AU in 2017, Algeria managed to assemble a base of 21 states right from the start of the electoral process. This raises questions about the factors that enabled this country to regain some of its influence, even though Morocco, which is going through a golden age of African policy in terms of political and economic power, seemed to hold all the cards.

Paradoxically, Algerian persuasion has benefited from Moroccan diplomatic successes. For example, Ambassador Fathallah Sijilmassi's performance over the past three years as DG of the Commission reinforced the idea, exploited by Algeria, that Morocco held disproportionate influence within the Commission, notably by occupying a strategic position (number 3). Consequently, it was unacceptable, according to the Algerian side, to allow Morocco to cumulate the positions of number 2 and number 3 of the Commission, in addition to a President of the Commission from Djibouti, favorable to Morocco.

Regardless of the undue influence exerted by Algeria and the exclusion of six countries friendly to Morocco from the voting process[8], it has to be admitted that the opponents’ arguments had a strong chance of convincing several countries. It was foreseeable that the latter feared that the election of Mrs. Latifa Akharbach would place the Commission under Moroccan control. This observation is in line with the sociology of the AU, where the major powers keep a watchful eye on each other, while the other countries fear that decision-making within the AU will be appropriated by a board of large member states.

An Uncertain and Risky Electoral Dynamic

The two considerations outlined above direct the analysis towards a complex game in which power dynamics determine the room for maneuver of member states, regardless of their status or weight:

- Balance of power: the great powers watch each other and seek to maintain their influence, while avoiding losing ground to their rivals;

- The trap of pre-eminence: the power game played by the major influential countries leads to a monopoly of leadership, sometimes at the expense of a genuine balance within the Union;

- Institutional balance: smaller states worry about the dominance of the larger states and engage in a game of countervailing power, mobilizing solidarity and support for a balanced institutional system.

If we transpose this scheme to the case studied, we can imagine a candidate A (Morocco) running against a candidate B (Algeria), while the states or stakeholders with voting power (C) are convinced that the election of A would lead to too great a concentration of power (Vice-presidency and General Management). Conversely, B is perceived as a less-threatening option for the institutional balance, giving B a clear advantage.

A's candidacy, despite this unfavorable dynamic, can be interpreted in different ways:

- Strategic mistake?

A was actively involved in an electoral process over which his influence seemed to be limited, falling into the trap of pre-eminence. He might have believed that his achievements, transparency, and alliances would be enough to convince the states, without taking into account their fear of institutional imbalance. This means that there was a certain confidence in A’s image and status, but these proved insufficient to achieve the desired objective;

- Lack of tactical foresight?

A therefore failed to anticipate the unpredictable and complex nature of the electoral process within the AU. He probably underestimated certain warning signs, such as the intensification of Algerian lobbying, or the changing expectations of voting states. In short, his self-satisfaction and disconnection from reality may have led him to be caught unawares by his defeat;

- Long-term calculation?

A may present itself not to win immediately, but to be present on the African stage and consolidate its legitimacy for future elections or negotiations. In fact, states sometimes run to test their influence, criticize the hegemony of certain players, or impose certain subjects on the diplomatic agenda;

- A bold bet on a turnaround?

A could hope that, at the last minute, certain states would change their minds under the influence of negotiations, alliances, or external pressures. Weakened from the outset by the absence of six friendly countries during the votes, A would have lost the last-minute negotiations to an opponent who would have resorted to financial incentives to rally the last undecided states to his cause.

Each of these four options is valid on its own merits, but they can also be combined to offer a more complete and nuanced understanding of the dynamics underlying the situation as a whole. In all cases, they reflect the complexity of institutional elections, in which the interplay of alliances and perceptions weighs as much, if not more in some cases, than the skills of the candidates themselves. It is therefore useful to take a realistic look at the institutional framework in which diplomacy takes place. The AU is essentially a cooperative organization, organizing competition in a context of precarious equilibrium. It is both an arbiter of competition and an arena of influence, favoring a political lock-in in favor of the most structured states.

Once this awareness has been established, the question arises of how to coordinate between the pre-eminence of intermediate objectives (occupying a position) and strategic pre-eminence (African power status). The former only makes sense if it serves the ultimate and constant objective. Also, an ill-considered commitment to an electoral process could affect Morocco’s reputation: in a word, mastering the electoral context, anticipating the risks and opportunities of the position at stake, and avoiding a perceived monopoly situation.

This implies, moreover, creating the conditions required for the emergence of a genuine collective analytical capacity: developing a collaborative approach, where the skills and knowledge of diplomats and researchers are pooled to improve the quality of analysis and decision-making. Above all, this approach is necessary for objective reasons. Given that foreign policy involves the country’s future, critical, contradictory, and responsible academic and political debate should be encouraged and taken into account, at least on issues for which expertise is essential to understand situations and exert influence. Diplomats, like soldiers, need constant support and trust. Faced with difficult situations with sometimes destabilizing consequences, they risk no longer being up to the complex demands of the African context in particular. Furthermore, the AU is a difficult place to work because of its intergovernmental mode of governance, based on negotiation in a context marked by ego-politics, rivalries, greed, and games of alliances and counter-alliances.

Conclusion

Morocco and Algeria are engaged in a duel in which anything goes. It’s a situation that Rabat didn’t choose, that was imposed on it, and that seems to have all the conditions to be long-lasting. The lasting projection of this geopolitical tension on the African continent illustrates a dynamic of rivalry for influence within the AU. The election results represent a major strategic setback for Morocco, especially as Algeria’s accession to institutional power could enable it to redefine priorities, notably by insisting on the Sahara issue, and to shape decision-making mechanisms in its favor.

The challenge is to anticipate and counter this reversal of influence through institutional, legitimate, and discreet means. In so doing, Morocco will protect its own strategic interests while remaining faithful to the principles of multilateral functioning: its ability to constantly mobilize its network of friendly countries, to fill its quota of positions of responsibility, and to inspire institutional discourse, will be decisive in managing this rivalry.

[1] Elections to the Commission are held every four years.

[2] During the 10th National Security Symposium 2023 (May 17-19), in Kigali, Rwanda. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ay7R5-EeWQQ

[3] Adopted at the 31st African Union (AU) Summit in Nouakchott, July 2018.

[4] Heads of State and Government are selected by the AU as Champions to promote African initiatives in a number of priority areas. See the list of Champion Heads of State: https://au.int/fr/presidents-champions-fr.

[5] Pr. Rachid EL Houdaigui https://papsrepository.africa-union.org

[6] Pr. Rachid El Houdaigui, Maha Ghazi https://www.peaceau.org/en/article/african-union-journal-on-post-conflict-reconstruction-and-development-peacebuilding-work-volume-1-issue-1-2024

[7] https://www.peaceau.org/en/article/au-launches-the-african-network-of-think-tanks-for-peace-nett4peace

[8] Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Gabon, Guinea and Sudan.Their suspension from the AU means the loss of their voting rights, among other things...