Publications /

Policy Brief

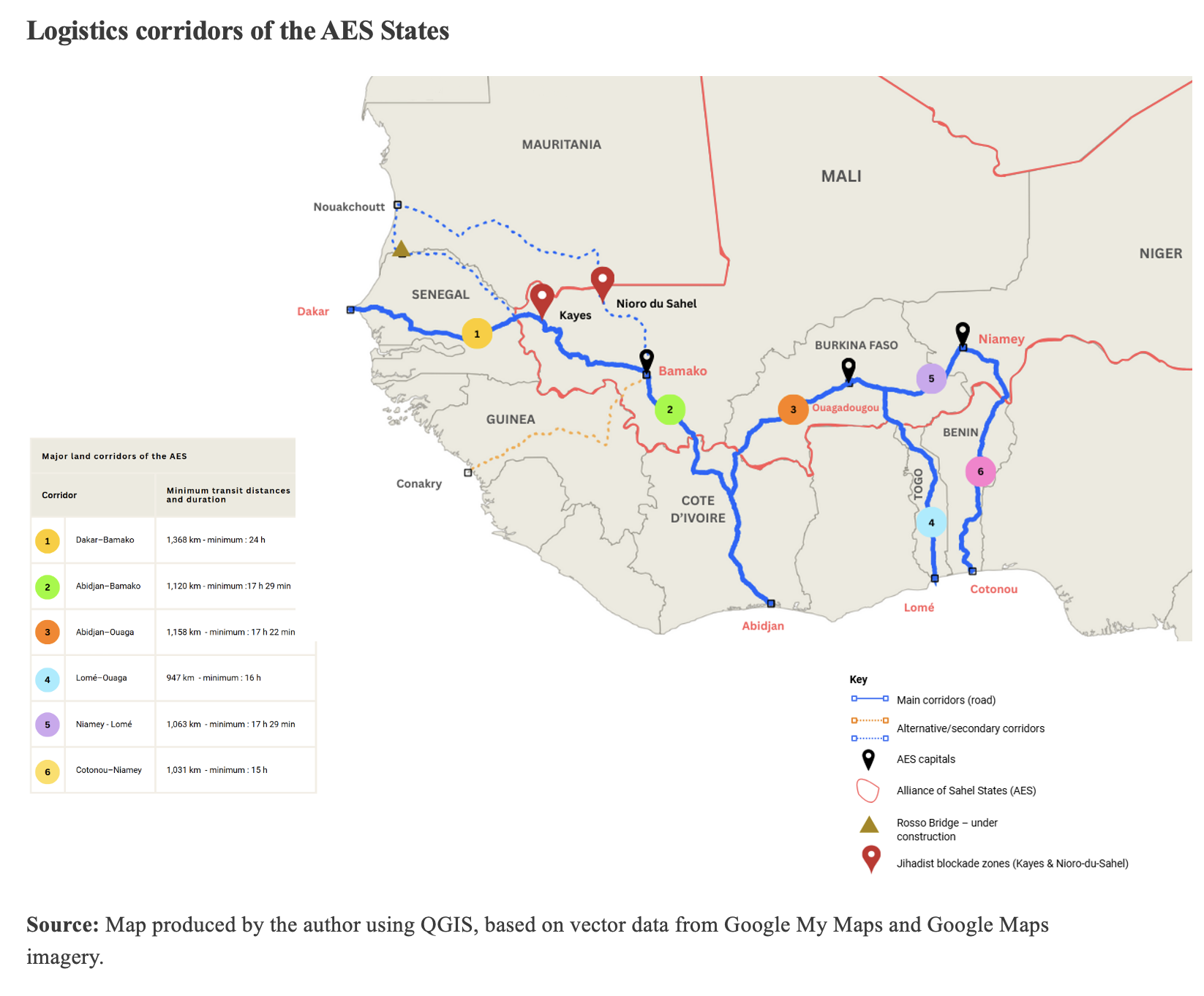

The member countries of the Alliance of Sahel States, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, remain dependent on a limited number of maritime access corridors, a configuration that constrains their adjustment capacity in the event of disruption and heightens the vulnerability of their supply chains. The Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) blockade of the Kayes-Nioro area revealed how critical the Dakar-Bamako corridor is for the political and economic stability of Mali. Its interruption led to a rapid disruption of flows, exposing the limited absorption capacity of alternative routes. In addition, the political and regulatory tensions between Burkina Faso and Niger hinder the efficiency of the Abidjan-Ouagadougou and Cotonou-Niamey corridors. Alternative routes via Conakry or Nouakchott offer only limited flexibility due to low port and road infrastructure quality. These issues are further compounded by the heterogeneity of customs regimes and the presence of illicit flows along several roads. The Kayes-Nioro blockade episode is a relevant case study for observing how these disruptions spread and measuring their operational implications for AES states.

1. Introduction

The countries of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) - Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, all landlocked - rely on a limited number of corridors to access Atlantic ports. This logistical concentration is a risk to their economies, as the disruption to a single axis can undermine national supply chains, increase transportation costs, and slow cross-border trade. Recent events highlight this vulnerability, including disruption along certain Burkinabè routes, prolonged tension between Niamey and Cotonou, and persistent constraints affecting Atlantic port capacities. The blockade of western Mali’s Kayes-Nioro axis in September 2025 by JNIM illustrates this dynamic: by disrupting a segment of the Dakar–Bamako corridor, the blockade highlighted how a non-state actor can disrupt a strategic logistics axis by targeting traffic flows.

This vulnerability emerges against a backdrop of regional reconfiguration, marked by the withdrawal of the AES countries from ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States), weakened regional coordination, and the rise of hybrid risks that combine insecurity, political rivalries, and criminal activities along key corridors. In response to these vulnerabilities, Sahelian capitals are exploring alternative routes, notably through Conakry or Lomé. However, the viability of these routes remains constrained by port capacities, the poor condition of road infrastructure, and still-insufficient levels of technical coordination.

This Policy Brief examines the main dependencies that weaken Sahelian corridors, the dynamics that disrupt their functioning, and diversification options toward the Atlantic. It identifies the factors underpinning the logistical vulnerability of the AES, and highlights the challenges associated with securing transport axes, strengthening regional cooperation, and sustainably improving port capacities.

2. The Logistical Architecture in the Sahel: Dependencies, Capacities, and Operational Constraints

The routes used by Sahelian states to gain access to the sea reflect different national configurations shaped by their landlocked status, available port capacities, the condition of road networks, and regional political interactions. Logistical flows depend on these parameters, which help explain the differentiated adjustment patterns in each of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

2.1. National Corridor Configurations

2.1.1. Mali: Logistical Concentration and Security Constraints

The Dakar-Bamako corridor is Mali’s primary supply axis. Approximately 2 million to 3 million metric tons of goods transit through this corridor each year, accounting for more than 60% of the country’s import volumes[1]. Daily traffic is estimated at nearly 400 trucks, primarily along RN1 and N1, which connect Dakar to Bamako via Kayes and Kidira.

The overriding importance of the Dakar-Bamako corridor is also explained by investments undertaken by Senegal to improve transit fluidity. The Autonomous Port of Dakar has increased its handling capacity by modernizing procedures, notably through the digitalization of customs operations, which has reduced clearance delays for goods transiting to Mali. These developments are part of a broader port strategy that includes the development of the Ndayane deep-water port and the Sandiara dry port, both designed to expand capacity for Sahelian cargo[2].

Despite these modernization efforts, the corridor continues to face several structural constraints that affect transit fluidity. These include the deterioration of certain road segments, the number of checkpoints, and differences in administrative procedures at border crossings. The Kayes-Nioro segment is also exposed to recurrent security risks: incidents attributed to armed groups affiliated with JNIM[3] have disrupted movements of convoys, highlighting the sensitivity of Mali’s supply chains to local security dynamics.

In parallel, the Abidjan-Bamako corridor serves as a complementary axis for Mali’s foreign trade. The Autonomous Port of Abidjan, which has 34 berths[4] and handled approximately 40.1 million metric tons of cargo in 2024, offers advanced logistical capacities capable of absorbing part of Mali’s trade flows[5]. Côte d’Ivoire-Mali relations, however, were affected by diplomatic tensions in 2022[6], notably the arrest of Ivorian soldiers in Mali[7], and by trade restrictions linked to ECOWAS sanctions on AES states. Since 2024, trade has resumed in a context of gradual normalization. However, several logistical cooperation mechanisms remain limited.

Mali shows the vulnerability of a supply system reliant on a limited number of corridors exposed to security risks and regional political constraints. Strengthening logistical resilience requires securing of transport axes, consolidating operational cooperation with coastal states, and diversifying port outlets.

2.1.2. Burkina Faso: Diversity of Access and Political Sensitivity

The Abidjan-Ouagadougou corridor is one of Burkina Faso’s main access routes to Atlantic ports. Extending approximately 1,150 km, it combines significant road traffic with a rail connection operated by SITARAIL[8], which transports close to 900,000 metric tons of freight annually[9]. This route is vital for the country’s external trade, but its performance is regularly shaped by the regional political context. In April 2024, diplomatic tensions between Ouagadougou and Abidjan led to tighter border controls, resulting in longer transit times and higher transportation costs[10].

In this context, the Lomé-Ouagadougou corridor is one of Burkina Faso’s main alternative routes. It relies on the capacities of the Autonomous Port of Lomé, where the draft allows for the accommodation of large-capacity vessels and where total traffic reached 30.6 million metric tons in 2024[11]. The increased redirection of flows toward Lomé reflects both the port’s logistical performance and the stability of relations between Ouagadougou and Lomé. Togo, which has maintained a position of neutrality in the tensions between the AES and ECOWAS, and has engaged in several mediation efforts, offers a relatively predictable operational framework for Burkinabè operators.

The growing importance of the Lomé corridor highlights how sensitive Burkina Faso’s supply chains are to regional political configurations. This reorientation reflects an adjustment logic toward partners offering a more stable framework, and forms part of a broader trend within the AES, involving the gradual adaptation of supply routes in response to diplomatic and security constraints.

2.1.3. Niger: Port Dependence and Geopolitical Fragilities

The Cotonou-Niamey corridor is Niger’s main maritime access[12] route, accounting for most of its freight flows until 2023[13]. Between August and December 2023, Benin’s decision to suspend transit bound for Niger significantly disrupted trade, highlighting the vulnerability of this route to regional political tensions.

Since the lifting of regional sanctions, traffic between Benin and Niger has resumed, though in a context marked by limited trust between the administrations of both countries. Bilateral tensions persist, particularly over the reopening of border posts, and the management of the Benin-Niger pipeline. In 2024, several incidents at the Sèmè-Kpodji terminal, including the detention of Nigerien technicians responsible for monitoring crude oil loading operations, underscored the fragility of the dialogue between Niamey and Cotonou[14]. Despite mediation initiatives undertaken in 2025, some crossing points continue to operate at reduced capacity, meaning no full return to normal logistical operations.

The corridors serving Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger reveal a high concentration of maritime access points, the continuity of which remains sensitive to regional political and security developments. Disruptions along these axes have had immediate impacts on supply chains and logistical costs across AES states.

Identifying alternative routes, particularly via Conakry or Nouakchott, forms part of a strategy to reduce current dependencies, and to strengthen the continuity of trade with Atlantic seaboards.

2.2. Alternative Routes: Available Capacities and Operational Constraints

2.2.1. Conakry-Bamako: An Emerging Capacity Constrained by Structural Weaknesses

The Conakry-Bamako corridor remains a secondary route for Malian trade flows, because of limited port capacities, the condition of road infrastructure, and higher transit costs compared to other corridors. The Autonomous Port of Conakry, the main entry point for Guinea’s foreign trade, has seen increased utilization since 2023, when Guinea was one of the few remaining maritime access points available to Mali in the context of regional sanctions. This development is part of a broader framework of reinforced cooperation between Conakry and Bamako, including a transit agreement, and the opening of a Burkinabè office within the port, as part of AES initiatives[15].

The corridor is also used for the transit of strategic cargoes, contributing to a diversification of Mali’s supply modalities. However, the gradual increase in traffic flows has exposed several operational constraints, including frequent terminal congestion, limited handling capacities, and logistical costs that are higher than along the Dakar or Lomé corridors[16]. These factors reduce the port of Conakry’s ability to absorb a larger volume of Malian traffic.

According to (open) sources, the corridor has recently been used to transport military equipment to Mali. These sources claim to have witnessed armoured vehicles arriving in Conakry before being transported by land to Bamako. Without altering the main commercial function of the route, this dimension adds a political and security component that requires regular monitoring.

2.2.2. Nouakchott-Bamako: A Gradual and Constrained Scale-Up

The Nouakchott-Bamako corridor offers an additional maritime access option to Mali. By linking the country to Mauritania, which is not an ECOWAS member, it offers a transit route outside the region’s usual logistical circuits. The growing use of this corridor reflects the search for alternative solutions in response to the political and logistical constraints affecting the traditional routes used by AES countries.

The commissioning of the Rosso Bridge, a cross-border infrastructure project supported by the European Union and the African Development Bank (AfDB), was an important step in the development of the Nouakchott-Bamako corridor[17]. The completion of the project, scheduled for 2026, is expected to improve border crossing conditions and to strengthen route continuity via Néma and Nioro.

At the operational level, Mauritanian and Malian authorities have strengthened their coordination since 2024, particularly on transit facilitation and the security of the Nioro–Néma segment, identified as one of the most vulnerable because of the activity of armed groups in the surrounding areas. Mauritania maintains a position of neutrality toward ECOWAS and the AES, which contributes to the continuity of bilateral dialogue, and supports the development of this corridor.

Though still underdeveloped, the Nouakchott-Bamako corridor is an additional connectivity option for AES states toward the Atlantic seaboard. Over the medium term, its use could contribute to diversifying the maritime access points available to the region. Its viability, however, remains contingent on the securing of transit areas, improvements in road infrastructure, and the establishment of predictable transit procedures for economic operators.

2.2.3. Rail Network: Service Disruptions and Infrastructure Limitations

For more than a decade, the Sahelian rail network has seen continuous infrastructure degradation and a significant decline in operational capacity. The Dakar-Bamako line (1,287 km), on which traffic is largely suspended at present because of the poor condition of structures and insufficient maintenance, has been the subject of revival initiatives led by the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) and the Infrastructure Project Preparation Program (IPPP). The suspension of rail services has resulted in the diversion of flows to road transport, increasing pressure on the region’s main transit corridors[18].

In 2025, an institutional mission was mandated to support the preparation of the first phase of the rehabilitation project, focusing on the Dakar-Tambacounda segment, identified as a prerequisite for restoring service along the entire line[19]. Several regional institutions and technical and financial partners, including the African Development Bank, are supporting the associated engineering and planning work. The project remains in the preparatory phase because of technical constraints, substantial modernization requirements, and financial needs that have yet to be secured.

Rail transport currently plays a limited role in regional trade in the Sahel, reflecting a low modal share and reduced operational capacity. Volumes transported remain below those transported by road, because of structural constraints including weak regional coordination, insufficient maintenance capacities, and the absence of fully functional cross-border links[20]. Revitalizing rail transport will require an integrated approach that combines targeted investment, strengthened technical governance, and sustained inter-state cooperation.

2.2.4. Air Freight: A Specific Logistical Contribution

Air transport complements land corridors for the logistical connectivity of Sahelian states, particularly for flows requiring short transit times, though regular cargo services remain limited. Since October 2023, Niger Air Cargo has operated a weekly rotation between Liège (Belgium) and Niamey, offering a monthly capacity of approximately 150 metric tons[21]. Emirates SkyCargo also operates a weekly Boeing 777 freighter service originating from Dubai on the Dubai-Ouagadougou-Dakar-Frankfurt-Dubai route, contributing to the integration of Sahelian countries into international logistics networks[22]. Data on Sahelian air freight remain fragmented and infrequently updated, making it hard to accurately assess transported volumes and available operational capacities.

The analysis of corridors highlights a logistics network with limited room for adjustment, within which targeted disruptions can have significant ripple effects. The Kayes-Nioro blockade episode is a relevant case study for observing how these disruptions spread and measuring their operational implications for AES states.

3. The Kayes-Nioro Blockade: Exposing Logistical Vulnerabilities

3.1. An Example of Disruption Along a Critical Corridor

Since June 2025, groups affiliated with JNIM have imposed their control over the Kayes-Nioro axis, which is essential for transport toward Bamako[23]. The disruption of this segment severely impacted flows, highlighting Mali’s operational dependence on the Dakar-Bamako corridor. The closure, even partial, of RN1 immediately affected supply continuity, in the absence of alternative routes capable of absorbing the diverted volumes.

Attempts by transport operators to redeploy toward southern routes via Côte d’Ivoire or toward Mauritania quickly showed their limits, as these axes were themselves subject to JNIM pressure. This dynamic reflected more a displacement of risk than a genuine substitution capacity[24].

Beyond its immediate impact on traffic flows, the blockade generated a series of significant internal effects:

Economic and Logistical Impacts

Acute fuel shortages, leading to a reduction in mobility, a rapid increase in prices, and disruption to transport, energy, and essential service sectors.

Slowdown in the gold sector, a pillar of Mali’s export economy, because of supply constraints and rising logistical costs.

Social Impacts

Suspension of classes across the national education system in late October 2025, a decision taken in response to mobility constraints and reduced energy availability.

Reduced functionality of hospitals and public services, affected by transport and supply constraints.

Security and Political Impacts

Preventive evacuation of non-essential personnel by several embassies, reflecting heightened security concerns in Bamako.

Increased perceptions of vulnerability among border communities, which are frequently exposed to service disruptions and shortages of basic goods.

The Kayes-Nioro blockade therefore illustrates how a localized disruption can generate systemic effects within an already constrained logistical environment. To understand the mechanisms that amplify these dynamics, it is necessary to examine the structural factors that condition the resilience of Sahelian corridors.

3.2. Underlying Factors of Corridor Vulnerability

The Kayes-Nioro case highlights several structural constraints that limit the resilience of Sahelian corridors. The five most decisive factors in the current configuration of the AES logistics system are:

Dependence on a limited number of axes: Most AES import and export flows pass along a small number of corridors that lack sufficient diversion capacity in the event of disruption. This low level of operational redundancy constrains the system’s ability to adjust: the failure of a single axis can lead to significant breaks in national supply chains;

Security exposure along corridors: According to the Roads and Conflicts in North and West Africa study, published by the OECD/SWAC in 2025, nearly 70% of violent incidents recorded in the region occur within a few kilometers of major roadways[25]. This concentration reflects the vulnerability of crossing points and transit zones, where armed groups target convoys and checkpoints. These dynamics disrupt the continuity of flows and increase the risks faced by logistics operators;

Infrastructure constraints and port congestion: The variable quality of road networks, particularly of cross-border segments, limits the regularity and predictability of overland transport within the AES. Meanwhile, several ports in the region operate close to their nominal capacities, increasing handling times during periods of high demand. The application, in 2025, of a Port Congestion Surcharge (PCS) by CMA CGM at the Port of Conakry illustrated this situation[26], demonstrating that any capacity overrun translates into an immediate rise in logistical costs, and in reduced trade fluidity;

Political fragmentation and regulatory misalignment: Successive political transitions within the AES, combined with regional sanctions and evolving relations with ECOWAS, have increased uncertainty around transit regimes and border procedures[27]. The absence of harmonized customs control mechanisms and the intermittent closure of borders, illustrated in particular by tensions surrounding the Niger-Benin pipeline[28], disrupt the continuity of trade flows and undermine the predictability required by logistics operators;

Criminal infiltration of corridors: Several Sahelian road segments are traversed by illicit flows, including fuel, weapons, goods, and unauthorized movements, driven by networks that exploit the limited state presence in certain border areas[29]. These activities frequently intersect with regular commercial flows, increase the risks faced by transport operators, and complicate the implementation of coherent security arrangements along corridor routes.

These factors substantially constrain the adjustment capacity of the Sahelian logistics system. In an environment characterized by limited operational margins, localized disruption can generate disproportionate effects on flow continuity and supply conditions. This analytical framework helps clarify the significance of the Kayes-Nioro blockade and its implications for AES states.

3.3. Regional Implications and Stakes for AES States

The Kayes-Nioro blockade, interrupting a critical segment of the Dakar–Bamako corridor, led to a rapid deterioration in Mali’s supply performance, reflected in a contraction of flows, an increase in marginal transport costs, and disruption to urban and inter-urban distribution chains.

The resulting impacts have affected several essential functions: (i) reduced availability of strategic inputs, including fuel and intermediate goods; (ii) diminished operational capacity of public services and energy infrastructure; and (iii) a slowdown in extractive and industrial activities, particularly in areas that are highly dependent on high-turnover road logistics. These disruptions show that system resilience remains constrained by the absence of bypass routes, the limited capacity of alternative ports, and the weak integration of regional transport networks.

For AES states, this episode underscores the importance of adopting a systemic approach to logistical continuity. Securing corridors, improving infrastructure standards, reducing regulatory frictions, and developing modal shift capacities, whether port-based, rail, or multimodal, have become structuring parameters of economic stability. In an environment marked by growing interdependence between security and logistical performance, the ability of governments to maintain acceptable service levels in the face of shocks is a central indicator of institutional and macroeconomic resilience.

4. Conclusion

The analysis shows that the logistical performance of AES states continues to be constrained by limited corridors, uneven levels of road service, and a high exposure of critical segments to security-related disruptions. The Kayes-Nioro episode illustrates a breakdown scenario for a system operating near maximum capacity, without bypass routes that can ensure functional continuity under stress conditions.

Insecurity, infrastructure-related constraints, and regulatory frictions among neighboring states generate cumulative effects that reduce the system’s adjustment margins, and increase supply chain sensitivity to exogenous shocks. In this context, Sahelian logistics are characterized by a high degree of dependence on ‘single points of failure’, with the disruption of a single segment leading to a rapid deterioration in indicators related to goods mobility, availability of strategic inputs, and continuity of essential services.

The interaction between security risks, operational constraints, and insufficient regional coordination underscores the need for analytical approaches that more fully combine infrastructure criticality, nominal capacity, systemic resilience, and business-continuity considerations. As long as these factors persist, the stability of logistics flows will remain conditioned by narrow operational margins and high sensitivity to localized disruption.

The study thus confirms the relevance of further research into corridor vulnerability, disruption-scenario modeling, and the assessment of modal-shift capacities, with a view to informing the strategic trade-offs required to improve regional logistical performance over time.

References

« Corridors : le blocus de Nioro met Bamako sous pression », Journal du Mali, juillet 2025. https://www.journaldumali.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/JDMH534.pdf

« La bataille des corridors de l’AES : de nouveaux corridors en compétition rude avec les circuits commerciaux traditionnels », Africa Supply Chain Magazine 2024. https://africasupplychainmag.com/la-bataille-des-corridors-de-laes-de-nouveaux-corridors-en-competition-rude-avec-les-circuits-commerciaux-traditionnels/

« At least 40 fuel tankers burned in al Qaeda-linked attack in Mali, sources say », Reuters, 15 septembre 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/least-40-fuel-tankers-burned-al-qaeda-linked-attack-mali-sources-say-2025-09-15/

« Les chiffres clés du port d’Abidjan », Port Autonome d’Abidjan. https://www.portabidjan.ci/fr/le-port-dabidjan/les-chiffres-cles

« Activités sectorielles - Transport maritime », Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances de Côte d’Ivoire. https://www.dev.economie-ivoirienne.ci/activites-sectorielles/transport-maritime.html

« Ivory Coast asks Mali to immediately release 49 arrested soldiers », Reuters, 12 juillet 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/ivory-coast-asks-mali-immediately-release-49-arrested-soldiers-2022-07-12/

« Ivory Coast: The Port of Abidjan faces stiff competition from other regional hubs », SouthWorld , 2024. https://www.southworld.net/ivory-coast-the-port-of-abidjan-faces-stiff-competition-from-other-regional-hubs/

« Performances du Port autonome de Lomé en 2024 : le trafic global en progression de 18,5 % », . https://atop.tg/performances-du-port-autonome-de-lome-en-2024-le-trafic-global-en-progression-de-185/

Agence Togolaise de Presse (ATOP),

« Le Sahel : un espace d’enclavement multiple », Policy Paper, Nezha Alaoui M’hammdi et Larabi Jaïdi, 2021 https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/le-sahel-un-espace-enclavement-multiple

‘’ Benin removes suspension of transiting goods to Niger’’, Africanews, 28 décembre 2023. https://www.africanews.com/2023/12/28/benin-removes-suspension-of-transiting-goods-to-niger/

, « Relations compliquées entre le Bénin et le Niger », Republic of Togo, 7 juin 2024. https://www.republicoftogo.com/toutes-les-rubriques/region-afrique/relations-compliquees-entre-le-benin-et-le-niger

, « À Bamako, des voyageurs transfrontaliers bloqués par les sanctions de la CEDEAO », Le Monde ,12 janvier 2022.https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2022/01/12/a-bamako-des-voyageurs-transfrontaliers-bloques-par-les-sanctions-de-la-cedeao_6109117_3212.html

, « Construction of the Rosso Bridge between Mauritania and Senegal », European External Action Service (EEAS), 24 novembre 2022. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/mauritania/construction-rosso-bridge-mauritania-senegal_en

Banque mondiale. Projet P171122 - Programme de Réhabilitation du Chemin de Fer Dakar-Tambacounda : Document d’information environnementale et sociale, 2021. https://ewsdata.rightsindevelopment.org/files/documents/22/WB-P171122_GEnziyK.pdf

Programme pour le Développement des Infrastructures de la CEDEAO (PPDU). « Mission de haut niveau pour accélérer la mise en œuvre de la phase 1 de la ligne ferroviaire Dakar-Bamako et du corridor multimodal Praia-Dakar-Abidjan », 3-4 juillet 2025.https://ppdu.org/v22/fr_fr/3-4-juillet-2025-mission-de-haut-niveau-pour-accelerer-la-mise-en-oeuvre-de-la-phase-1-de-la-ligne-ferroviaire-dakar-bamako-et-du-corridor-multimodal-praia-dakar-abidjan/

Banque mondiale. Projet P178362 - SITARAIL Railway Rehabilitation Project: Environmental and Social Review Summary (ESRS), juin 2025. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099061825113091598/pdf/P178362-219cb2d2-911a-4c0f-a3e7-580a17ca536d.pdf

Emirates SkyCargo launches weekly freighter service to Burkina Faso », AACO, 29 jan 2015. https://www.aaco.org/media-center/news/aaco-members/emirates-skycargo-launches-freighter-service-to-burkina-faso

« ECS Group’s Niger Air Cargo resumes weekly B747 service », Air Cargo Vision, 15 nov 2023. https://aircargovision.net/ecs-restarts-niger-flight/

“Jihadists’ fuel blockade poses biggest threat yet to Mali’s military rulers.”, Reuters, 3 novembre 2025. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/society-equity/jihadists-fuel-blockade-poses-biggest-threat-yet-malis-military-rulers-2025-11-03/

« Des barrages routiers terroristes étranglent les économies du Mali et de ses voisins », Institute for Security Studies (ISS Africa), 23 septembre 2024. https://issafrica.org/fr/iss-today/des-barrages-routiers-terroristes-etranglent-les-economies-du-mali-et-de-ses-voisins

OCDE / Club du Sahel et de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (SWAC). Roads and Conflicts in North and West Africa, février 2025. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/02/roads-and-conflicts-in-north-and-west-africa_4892fa2e.html

« Frontière fermée, pétrole bloqué : la tension monte entre le Niger et le Bénin », Le Monde, 10 juin 2024. https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/06/10/frontiere-fermee-petrole-bloque-la-tension-monte-entre-le-niger-et-le-benin_6238463_3212.html

« Subject: Port Congestion Surcharge (PCS) for Conakry, Guinea », CMA CGM Group, 1er septembre 2025.https://www.cma-cgm.com/local/pakistan/news/400/subject-port-congestion-surcharge-pcs-for-conakry-guinea

Reuters, « Niger PM says Benin’s oil export blockade violates accords », Reuters,, 12 mai 2024.https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/niger-pm-says-benins-oil-export-blockade-violates-accords-2024-05-12/

« Drug trafficking undermining stability and development in Sahel region, says new report from UNODC », United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 23 avril 2024. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/frontpage/2024/April/drug-trafficking-undermining-stability-and-development-in-sahel-region--says-new-report-from-unodc.html

[1] « Corridors : le blocus de Nioro met Bamako sous pression », Journal du Mali, juillet 2025.

[2] « La bataille des corridors de l’AES : de nouveaux corridors en compétition rude avec les circuits commerciaux traditionnels », Africa Supply Chain Magazine 2024.

[3] « At least 40 fuel tankers burned in al Qaeda-linked attack in Mali, sources say », Reuters, 15 septembre 2025.

[4] « Les chiffres clés du port d’Abidjan », Port Autonome d’Abidjan.

[5] « Activités sectorielles - Transport maritime », Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances de Côte d’Ivoire.

[6] « Ivory Coast asks Mali to immediately release 49 arrested soldiers », Reuters, 12 juillet 2022.

[7] On July 10, 2022, 49 Ivorian soldiers were arrested at Bamako airport. Malian authorities accused them of being mercenaries, while Abidjan stated that they had been deployed as part of a support arrangement for MINUSMA. The incident triggered several months of diplomatic tensions, before the soldiers were released in January 2023.

[8] SITARAIL (Société Internationale de Transport Africain par Rail) is a subsidiary of the Bolloré Group and holds a binational concession for the operation of the railway network linking Abidjan and Ouagadougou.

[9] « AES Corridors: A new rivalry with traditional trade routes », Logistafrica., 2024.

[10] « Ivory Coast: The Port of Abidjan faces stiff competition from other regional hubs », SouthWorld , 2024.

[11] « Performances du Port autonome de Lomé en 2024 : le trafic global en progression de 18,5 % », Agence Togolaise de Presse (ATOP).

[12] « Le Sahel : un espace d’enclavement multiple », Nezha Alaoui M’hammdi et Larabi Jaïdi, Policy Paper, Policy Center for the New South. 2021.

[13] “Benin removes suspension of transiting goods to Niger’’, Africanews, 28 décembre 2023.

[14] « Relations compliquées entre le Bénin et le Niger », Republic of Togo, 7 juin 2024.

[15] « La bataille des corridors de l’AES : de nouveaux corridors en compétition rude avec les circuits commerciaux traditionnels », Africa Supply Chain Magazine 2024.

[16] Ibid.

[17] « Construction of the Rosso Bridge between Mauritania and Senegal », European External Action Service (EEAS). 24 novembre 2022.

[18] Banque mondiale. Projet P171122 - Programme de Réhabilitation du Chemin de Fer Dakar-Tambacounda : Document d’information environnementale et sociale, 2021.

[19] Programme pour le Développement des Infrastructures de la CEDEAO (PPDU). « Mission de haut niveau pour accélérer la mise en œuvre de la phase 1 de la ligne ferroviaire Dakar-Bamako et du corridor multimodal Praia-Dakar-Abidjan », 3-4 juillet 2025.

[20] Banque mondiale. Projet P178362 - SITARAIL Railway Rehabilitation Project: Environmental and Social Review Summary (ESRS), juin 2025.

[21] « ECS Group’s Niger Air Cargo resumes weekly B747 service », Air Cargo Vision, 15 nov 2023.

[22] «Emirates SkyCargo launches weekly freighter service to Burkina Faso », AACO, 29 janvier 2015.

[23] “Jihadists’ fuel blockade poses biggest threat yet to Mali’s military rulers.” Reuters. 3 novembre 2025.

[24] « Des barrages routiers terroristes étranglent les économies du Mali et de ses voisins », Institute for Security Studies (ISS Africa), 23 septembre 2024.

[25] Roads and Conflicts in North and West Africa, OCDE / Club du Sahel et de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (SWAC), février 2025.

[26] « Subject : Port Congestion Surcharge (PCS) for Conakry, Guinea », CMA CGM Group. 1er septembre 2025.

[27] « Niger PM says Benin’s oil export blockade violates accords », Reuters. 12 Mai 2024.

[28] « Frontière fermée, pétrole bloqué : la tension monte entre le Niger et le Bénin », Le Monde, 10 juin 2024.

[29] « Drug trafficking undermining stability and development in Sahel region, says new report from UNODC », United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 23 Avril 2024.