Publications /

Opinion

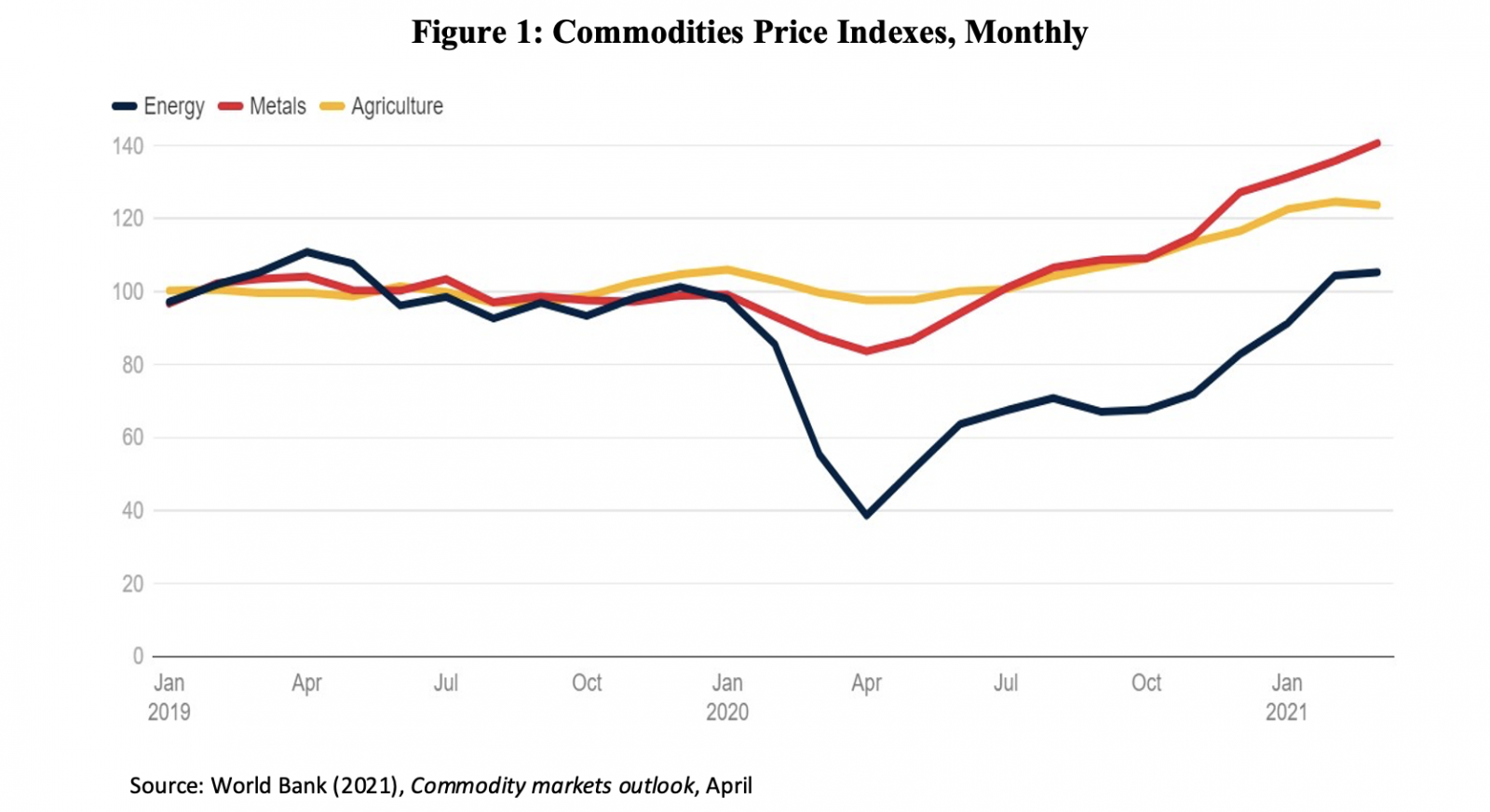

Commodity prices have recovered their 2020 losses and, in most cases, are now above pre-pandemic levels (Figure 1). The pace of Chinese growth since 2020 and the economic recovery that has accompanied vaccine rollouts in advanced companies are seen as driving demand upward, while supply restrictions for some items—oil, copper, and some food products—have favored their upward adjustment.

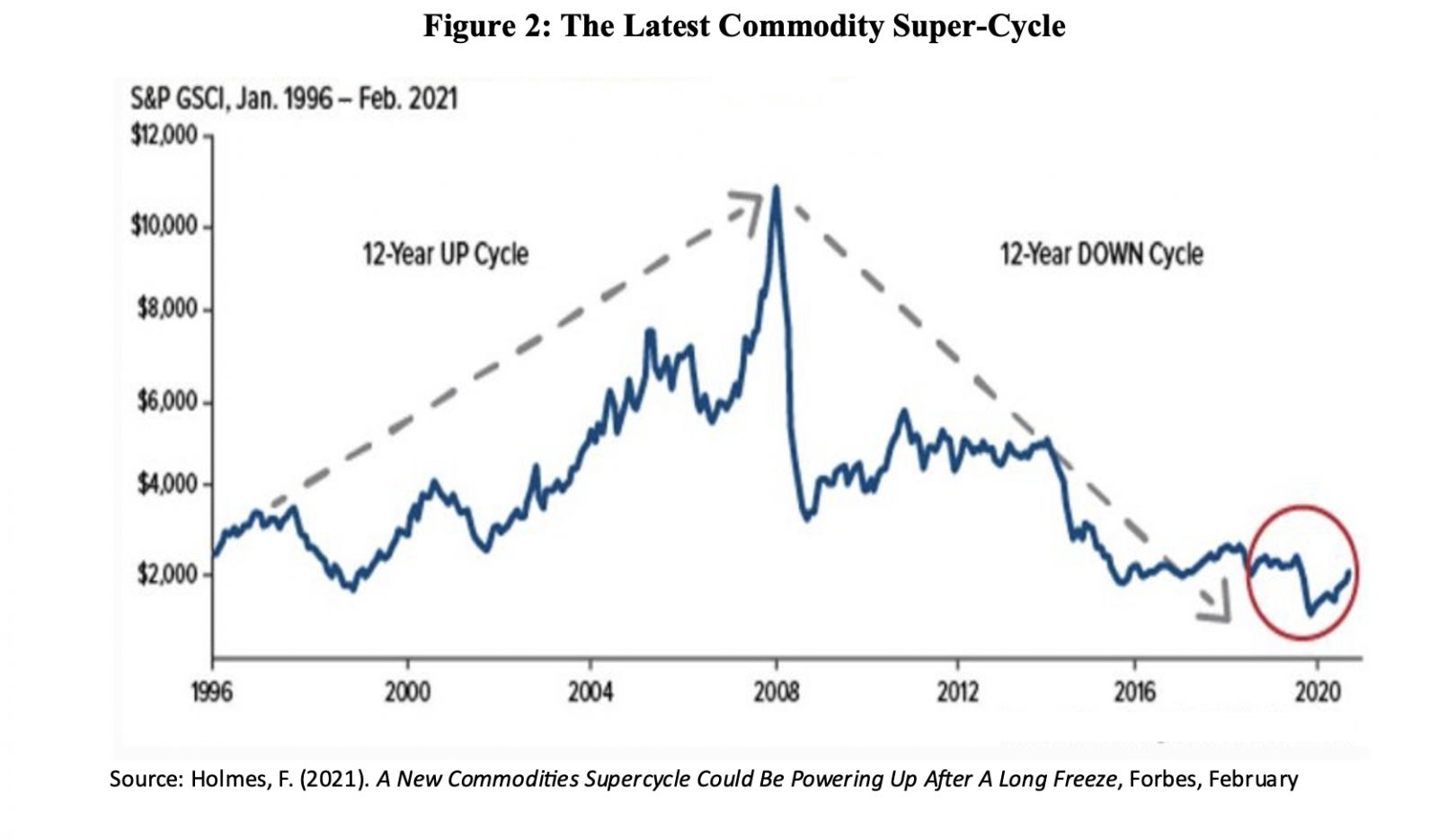

Some analysts have started to speak of the possibility of a new commodity price ‘super-cycle’ after the downturn that started in 2010 (Holmes, 2021; Sullivan, 2020). There is an expectation that Chinese growth will eventually return to the levels of its ‘rebalancing’, below those rates that sustained the global demand for commodities in the previous long price upswing. However, there is the perspective of a strong macroeconomic acceleration in the USA—and possibly also in Europe—driven by public spending packages in green infrastructure.

Why are Commodity Prices so Cyclical?

Commodity prices go through extended periods during which they are well above or well below their long-term trends. The upswing phase in commodity super-cycles occurs when unexpected, persistent, and positive demand trends contrast with typically slow-moving supply. Eventually, as more supply becomes available and demand growth slows, the cycle enters a downswing phase.

Individual commodity groups have their own price patterns. But when charted together they display extended periods of price trends known as ‘commodity super-cycles’. Commodity super-cycles are different from occasional supply disruptions, because high or low prices persist over time.

Four distinct commodity price super-cycles since the end of the nineteenth century can be linked to dramatic structural changes and corresponding growth periods in some regions of the planet.

- The cycle from 1899 to 1932—with up and down phases—that coincided with the industrialization of the United States in the late nineteenth century.

- The cycle from 1933 to 1961, the upswing phase of which reflected the onset of global rearmament before the Second World War.

- The cycle of 1962 to 1995, with the boom period associated with the reindustrialization of Europe and Japan in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

- Finally, the cycle starting in the mid-1990s and lasting until now is mostly related to the rapid industrialization of China up to its re-balancing phase. The pattern of high growth of the global economy in this period saw fast-growing countries generating higher proportions of GDP from natural resources, i.e. commodities.

Figure 2 depicts the latest super-cycle, as measured by the S&P GSCI spot index, which tracks price movements for 24 raw materials. The abrupt decline in 2015 mainly reflected a sharp drop in oil prices, as US shale gas and oil altered the supply landscape. Notice that, after the impact of the pandemic in 2020, the index has risen by close to 25% in 2021.

Some Commodities are More Equal than Others

It should be recalled that different groups of commodities have their own histories, reflecting their own conditions of demand and supply. Although it is always possible to find moments of joint fluctuation, in which commodities remained for a long time above or below their long-term trends, constituting commodity price super-cycles, one still should not lose sight of the differences between them.

Take the case of oil, the price of which plunged in 2020 when mobility restrictions directly impacted demand for oil derivatives. Oil’s recent rapid recovery happened at record pace, helped by production cuts in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and its partners. But the recovery in demand has been gradual and is expected to be steady only over the course of 2021, as vaccination unfolds and as travel restrictions begin to be reversed, especially in advanced economies. However, the global level of idle oil production capacity remains high.

Agricultural prices, on the other hand, are 20% higher than a year ago, reaching levels not seen for almost seven years. Price increases have been driven by declines in the supply of some food commodities, especially corn and soybeans, strong demand for feed in China, and the devaluation of the U.S. dollar. Soy has recently hit its highest price in eight years.

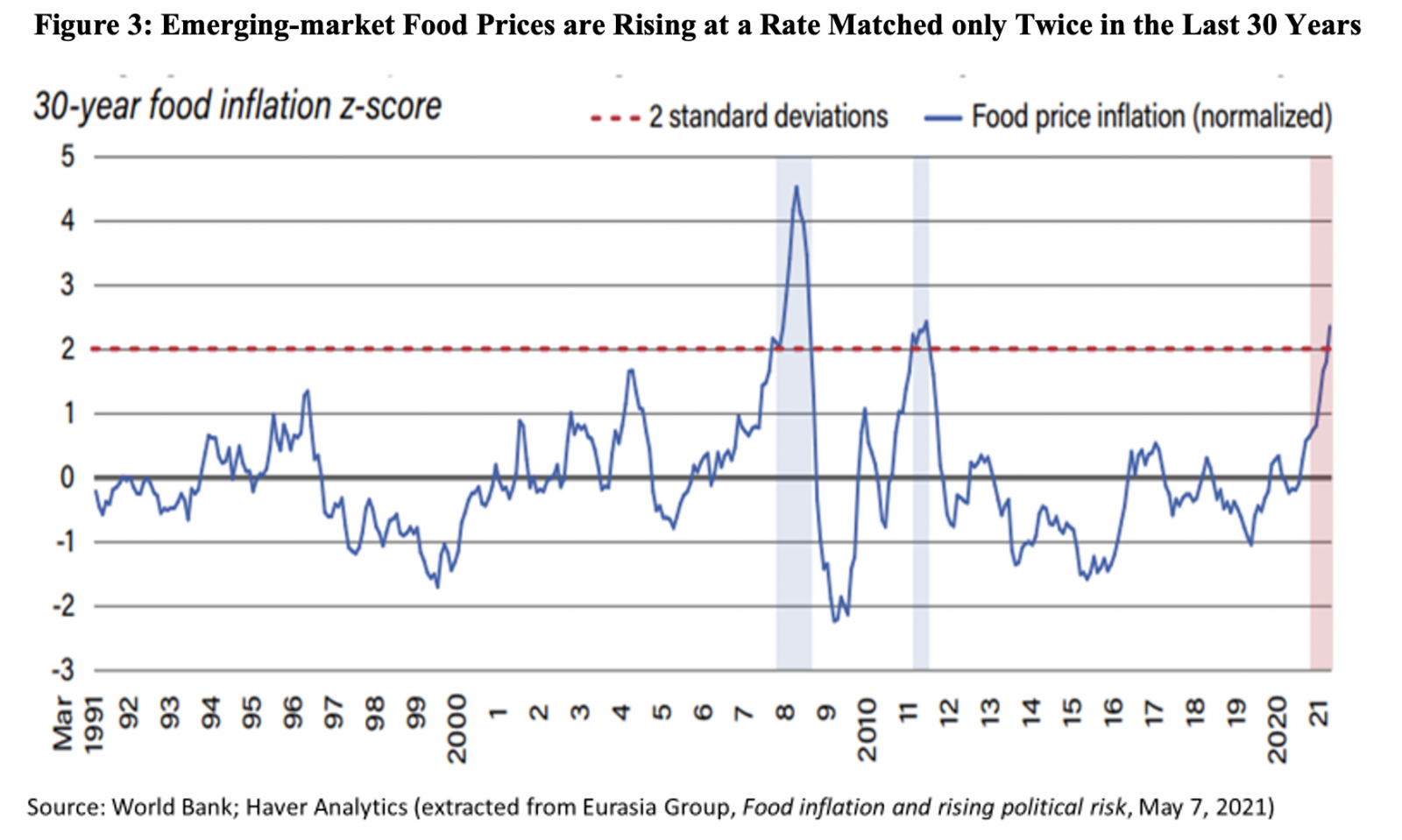

A report from the Eurasia Group (Food inflation and rising political risk, May 7, 2021) has called attention to rising political risks associated with recent food inflation in emerging markets. Several factors have accounted for that, including exchange rate depreciation, shipping constraints, logistical difficulties, and weather events.

Figure 3 shows the normalized food inflation rate on the World Bank’s measure of food prices for low- and middle-income countries over the last 30 years. According to this index, food inflation for developing countries was above 37% year-on-year in March 2021, or more than 2.3 standard deviations above the thirty-year mean. In the last three decades, the index has matched or exceeded this level only twice, during the food price crises of 2007-08 and 2011.

In its April 2021 report on commodities, the World Bank suggested factors that could stabilize food prices starting next year. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's survey of planting intentions, the land allocated for corn, soybeans and wheat in the U.S. is expected to increase next season—especially in the case of soybeans and wheat. This will follow supply growth below long-term trends during the last harvests. Given the U.S. weight in these commodities, if intentions are followed-through, increased planting will help stabilize global food commodity markets.

Agricultural prices are expected to stabilize in 2022, after a 13% increase this year. However, developments will also depend on the trajectory of energy costs in the short term and biofuel policies in response to the energy transition in the long term. Some analysts go as far as saying that the elasticity of agricultural production has become such that it makes cycles more a matter of quantity than prices.

Copper is King!

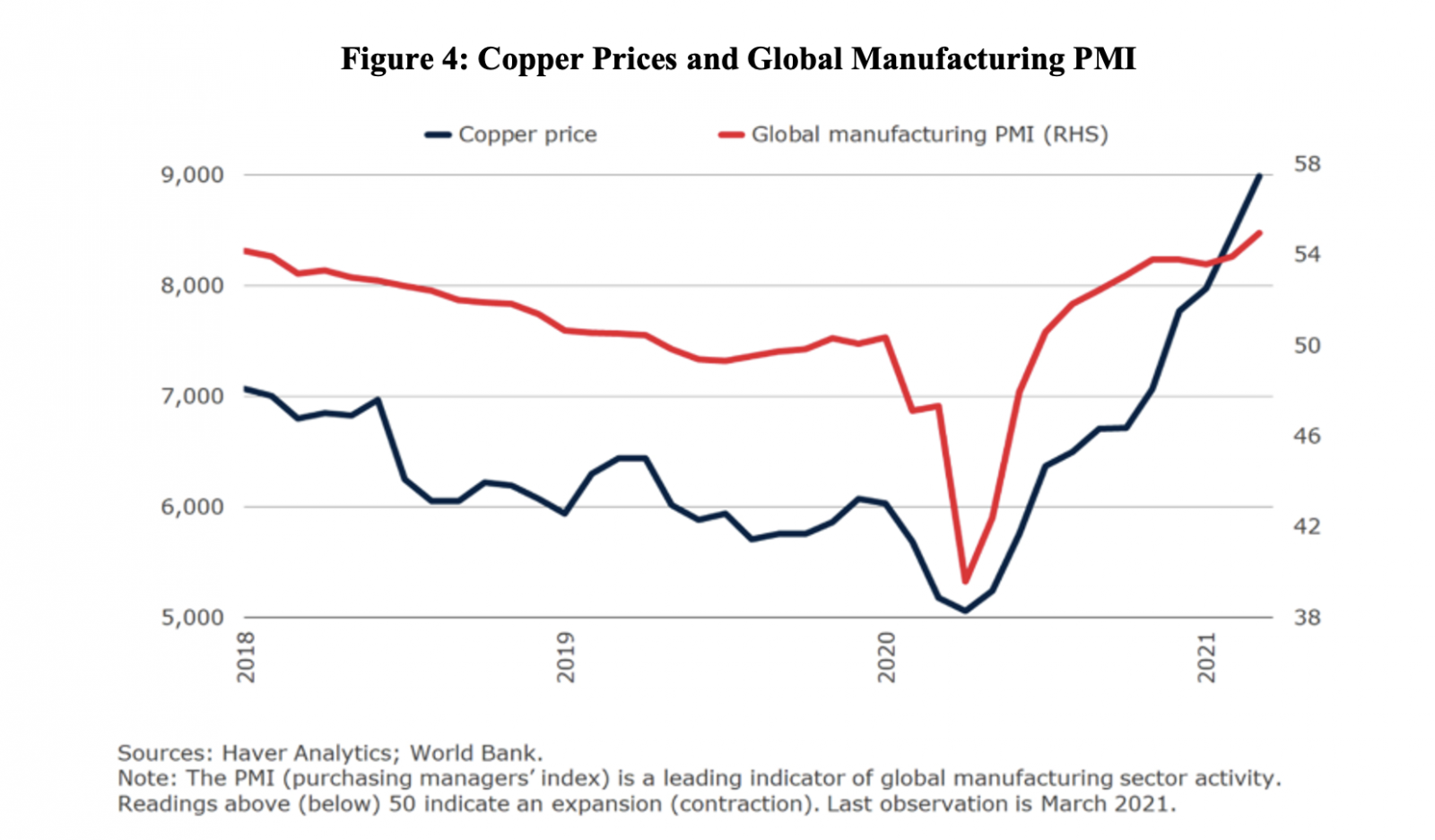

It is in metals, especially copper, that a strong bullish cycle is most evident. Prices currently on the rise reflect strong demand in China, the ongoing global recovery, and interruptions in the supply of some metals. In March 2021, copper, tin, and iron ore prices reached 10-year highs (Figure 4).

In the years ahead, the infrastructure spending package proposed by President Biden in the United States and the global energy decarbonization will impact demand and prices of commodities in different ways. President Biden's large infrastructure package will favor renewable energies, associated with the use of electric vehicles and batteries. The raw materials needed for batteries and electric vehicle engines —lithium, rare earths —are already experiencing market euphoria. Copper, because of its conductivity, tends to be used four or five times more in electric cars than in conventional combustion engine cars. Oil, of course, will not be in line with the ‘green recovery’.

Nicholas Snowdon, commodities strategist at Goldman Sachs Research, argues that because it is “the most cost-effective conductive metal [for] capturing, storing [and] transporting electricity,” copper will be the key metal in the transition to a green economy. “Copper is the new oil”, he says.

As it is typically the case under classic super-cycle conditions, there will inevitably be a delay in the supply response in the case of copper and other metals. It is only now, with the return of the U.S. to the Paris Agreement and the Biden program, that the infrastructure ‘greening’ is being taken for real. No major copper investment project has been approved in the past 18 months and such projects take four to five years to become fully operational. Investment losses at the start of the downturn in the past decade have led investors to hesitate to embark in new ventures.

Three things to note. First, even copper scraps are going to be valuable in the near future. Second, it will be interesting to see how copper mining projects that respect environmental, social, and governance safeguards are put together, in order to be in step with the new times. Third, the next time you hear about commodity super-cycles, ask what commodity is being talked about.