Publications /

Policy Brief

This article analyzes the role played by Türkiye as an emerging “middle power”[1], in Africa over the last two decades. It argues that a certain discontinuity can be identified in Türkiye’s foreign policy approach in Africa. The approach has shifted from short-term involvement with African nations to more focused, constructive, vision-oriented partnerships. In addition, Türkiye’s gradual rapprochement with Africa began with a soft-power approach through a humanitarian, cultural, and religious presence, but has evolved into a more political and military relationship. Amidst great power competition, Türkiye seems to offer African states an alternative option for economic, political, and security cooperation. This relationship enjoys support from African leaders because of a rhetoric promoted by the Turkish state that challenges the status quo of global governance institutions, promotes a neo-Ottoman vision of Muslim fraternity, and rallies for an ‘alternative’ model of global governance. This renewed interest in Africa is part of a broader effort to expand its influence beyond its immediate neighborhood, through the diversification of allies in political and economic spheres. Hence, the pivot to Africa is crucial for understanding the wider change in Turkish foreign policy.

From Dependence to Assertiveness

Various reasons have created a context for discontinuity in Türkiye’s foreign policy. In the post-Cold War era, Türkiye’s strategy shifted from “calculated pacifism and reluctance, to activism”[2]. During a period of major changes in the international order, Türkiye became more assertive in the Middle East and, particularly under the ruling Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP), focused its foreign policy on the Balkans, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Africa. The reshuffling of power during the critical wave of Arab Uprisings shifted Türkiye’s approach from ideological to more pragmatic. The Middle East became a “focal point of foreign policy initiatives, as Türkiye strove to position itself as a proactive ‘benign regional power’, capitalizing on its geopolitical identity as an interlocutor between West and East”[3]. As tensions with the West grew, Türkiye began exploring ties with the states often identified as ‘revisionist’, including Russia, China, and Iran. This is evidenced by economic cooperation with the Global South, participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and formal requests to join the BRICS+. Türkiye’s ‘bigger than five’ (the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, and China) agenda promoted its growing “activist role” in the international system[4]. This narrative resonates with African countries, which have been major advocates of global governance reforms, particularly of the United Nations Security Council.

For much of Türkiye’s history, its policymakers attempted to substantiate Türkiye’s European identity, with memberships of the Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). When the AKP came to power in 2002, the party promoted economic and political reforms that aligned with those of its European Union neighbors. Their motto, ‘zero problems with neighbors’, championed by then-Prime Minister Erdogan’s Chief Adviser, Ahmet Davutoğlu, was one of the priorities of the party’s foreign policy.

Over time, as Türkiye’s chances of joining the EU dwindled, and following tensions with EU countries over the migrant crisis of 2015/2016, Türkiye began forging an increasingly assertive foreign policy that claimed a more global strategic role. The growing assertiveness in Turkish foreign policy was compounded by the illiberal turn in Turkish domestic politics, after the coup attempt in 2016 and the constitutional referendum of 2017. This interplay between structural and domestic factors created space for Türkiye to maneuver in the domains of security and ‘hard’ politics within Africa, instead of remaining within the confines a soft-power approach. In addition, the retreat of the United States from global leadership and “the rise of the rest” has created windows of opportunity for Türkiye to carve out its own space in Africa[5].

As its foreign policy role veered from interdependence and reluctance to more assertiveness and ‘strategic depth’[6], Türkiye began redrawing the boundaries of its identity. From President Recep Tayyip Erdogan stating that the Turks always see themselves as “part of Europe” to referring to Türkiye as an “Afro-Eurasian state”, Türkiye’s narrative aim to both maintain leverage for EU integration, and promote Türkiye as an extra-regional power with an ‘African identity’. Turkish politicians are creating a “new geographical mental map” and a new “geographical imagination”, and as a consequence, are diversifying the country’s mechanisms of international engagement[7]. Whether under Ottoman, Kemalist, or Islamist rule, Türkiye’s self-definition as a ‘center state’, bridge, or mediator between civilizations has prevailed, taking on new forms over time.

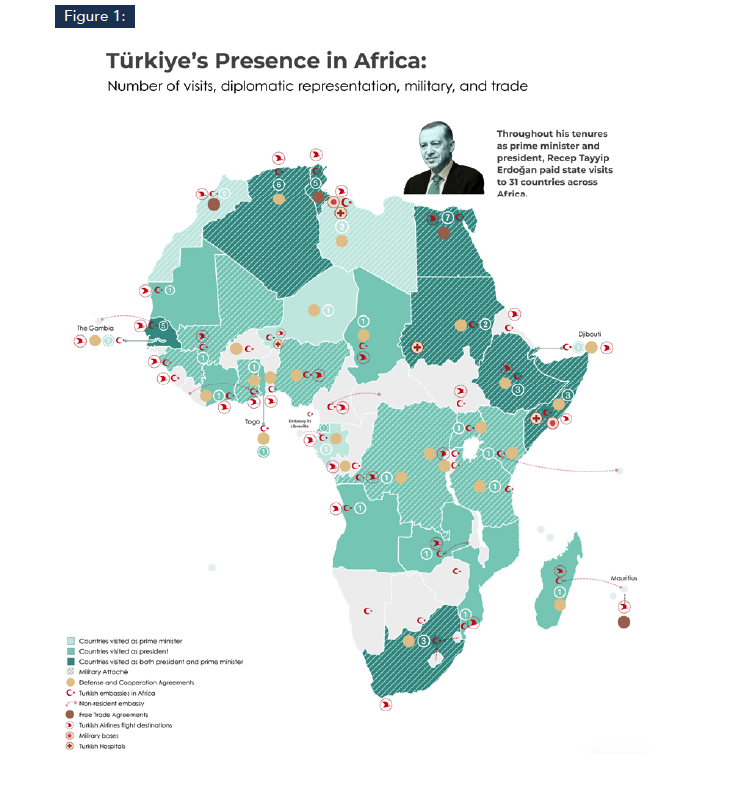

History of Türkiye’s Interest in Africa

Africa was largely negligible to Turkish politicians until the 1990s, when they decided to deepen diplomatic ties with African states through the 1998 African Action Plan for the Opening Policy towards Africa (Afrika Eylem Planı). Prior to that, Türkiye courted the votes of African states in forums such as the United Nations General Assembly, during a rapprochement in the 1960s and 1970s and expanded economic ties in the 1980s. However, it was during the 1990s when Türkiye truly sought to extend its reach beyond its immediate neighborhood and redefined its priorities to include Africa. Turkish interest in Africa expanded steadily in the 2000s, with 2005 designated the ‘Year of Africa’ in Türkiye, paving the way for greater diplomatic representation and multilateral coordination. In the same year, Türkiye obtained observer status at the African Union. Erdogan made his first visits to Ethiopia and South Africa, communicating to the entire continent that Türkiye has a new commitment to sub-Saharan countries. Eventually, Türkiye became an AU strategic partner in 2008, following the ‘Türkiye-Africa Cooperation Summit’ held in Istanbul in August of the same year. In 1997, Türkiye had diplomatic representation in South Africa. In addition to missions in the DRC, Ethiopia, Kenya, Senegal, and Sudan, Türkiye opened embassies in Cote d'Ivoire and Tanzania in 2009, and in Angola, Cameroon, Ghana, Madagascar, Mali, and Uganda in 2010[8]. In total, Türkiye has quadrupled the number of its embassies in Africa from 12 in 2005 to 44 in 2025.

From 2011 to 2012, the AKP formed new ‘friendship groups’ within the parliaments of 29 African nations, and the political connections between Türkiye and these African countries saw a significant increase during this administration. A new phase of Türkiye’s Africa agenda was introduced in 2014 under the auspices of the Türkiye–Africa Partnership program. Under the guiding principle that ‘African issues require African solutions’; this new approach would further support the consolidation of African ownership of African issues.

Sitting in pivotal geographies of place and identity, Türkiye claims exceptional moralism in Africa and ascribes to itself ‘virtuous power’ to create distance from traditional donors, such as the U.S., China, and Europe. According to Abdullah Gul, this power “is not ambitious or expansionist in any sense … [it is] a power that knows what’s wrong and what’s right and that is also powerful enough to stand behind what’s right”[9]. Not only does Türkiye define itself as a non-colonizing power, but it also says that it shares similar grievances with Africa, because of the aftermath of the First World War. In the context of Türkiye’s growing soft power in the 2010s, Fethullah Gülen has said the Turkish government wants to bring a “clean slate, with a humanist approach to Africa”[10].

Although Türkiye is heir to a significant empire, the AKP government has repeatedly engaged in postcolonial discourse to justify its policies and gain sympathy from actors in the Global South. From the sixteenth century on, ‘Ottoman Africa’ included territories in Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and the Red Sea, creating an interesting chapter in history that fostered new global connections and conceptions of identities[11]. Today, this history is used to create cultural and religious links between modern-day Türkiye and the modern Westphalian states of Africa.

The Horn of Africa is of particular strategic importance for Türkiye. It is where global and regional actors, including the Gulf states, the U.S., China, Russia, and the EU, all vie for influence. Erdogan’s visit to Somalia in 2011 symbolized the blend of humanitarianism and religious solidarity that has shaped Türkiye’s Africa policy. Accompanied by two hundred people, including his family, politicians, private-sector actors, and humanitarian workers, Erdogan brought international attention to a country in despair, experiencing the worst famine of the twenty-first century. This was a critical turning point for Türkiye’s influence in Africa. It enhanced the AKP’s popularity domestically, while creating support for Türkiye’s humanitarian endeavors abroad.

Between 2011 and 2025, Türkiye moved from being a minimal actor in Somalia to its fourth-biggest source of imports[12]. Turkish companies took over the Mogadishu airport from the Emirati company SKA in 2013, suggesting a struggle for economic and soft power between Türkiye and the Gulf states. Türkiye’s drive to enhance its ties with the Horn of Africa is, on the one hand, an expansion of economic interests and a way to counter the influence of rivals in strategic regions. Participation in aid initiatives created the perception that the Turks are ‘benevolent’, rather than seeking geopolitical interests or exploiting newly discovered offshore oil and gas resources, which are seen to be the main incentives for intervention by Western nations.

Türkiye was able to garner visibility because it filled a ‘diplomacy gap’ and delivered a development and peacebuilding approach that was seen as non-conditional. By establishing “niche diplomacy”[13], Türkiye was able to build a constructive role that distinguished it from major powers, even though other Western countries’ peacebuilding assistance in Africa exceeded that of Türkiye.

With the help of Fethullah Gülen, Türkiye’s soft power expanded through a movement of NGOs, schools, and businesses. Turkish foreign policy was one of ‘multitrack diplomacy’, involving non-state actors such as NGOs, businesses, charities, think tanks, and schools[14]. Networks associated with Fethullah Gülen helped expand Türkiye’s cultural and educational presence since the 1990s, contributing to Turkish soft power projection. “By 2013 the Gülen movement had opened over 100 schools in 50-odd countries across Africa”[15]. Hostilities between the AKP and Gülenist movement erupted in December 2013, their strategic alliance was strained, and the crisis acquired an international dimension, including in Africa. At the Second Turkey–Africa Summit in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea in 2014, Erdogan hinted at “vicious structures” that mysteriously operate to penetrate the states in Africa and to harm Türkiye-Africa relations[16]. The rupture took place particularly after the 2016 coup attempt and subsequent crackdown leading to the closure or transfer of many Gülen-affiliated institutions. The political hostilities within Türkiye were then externalized to the African theatre in order to break down the Gülenist movement’s transnational network. A strong diplomatic campaign was launched to close Gulenist institutions to deter the alleged ‘terrorist threat’ posed by the Gülenist movement to both Türkiye and Africa.

Türkiye refashioned its ‘multitrack diplomacy’, evolving from the relatively loose and decentralized form of the 2000s to a more tightly controlled approach over NGOs and business abroad in subsequent years. The Turkish government established a hybrid public-private institution called the Maarif Foundation on June 17, 2016, which has significant influence in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the head of Maarif, Dr. Birol Akgun, the main purpose was to replace and eliminate schools linked to the Gülen movement with this new predominantly governmental structure[17]. As of 2020, 125 Maarif Foundations are in Africa, with 63 operating specifically in countries of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)[18]. Various state-backed institutions remain integral to Türkiye's current cultural and religious soft power, including the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), Diyanet, and the Yunus Emre Institute, in addition to various scholarship programs for African students. The number of students from Africa has increased significantly since the 2000s, and today, over 60,000 students from 54 African nations study in Türkiye.

Making Sense of Türkiye’s Strategy in Africa

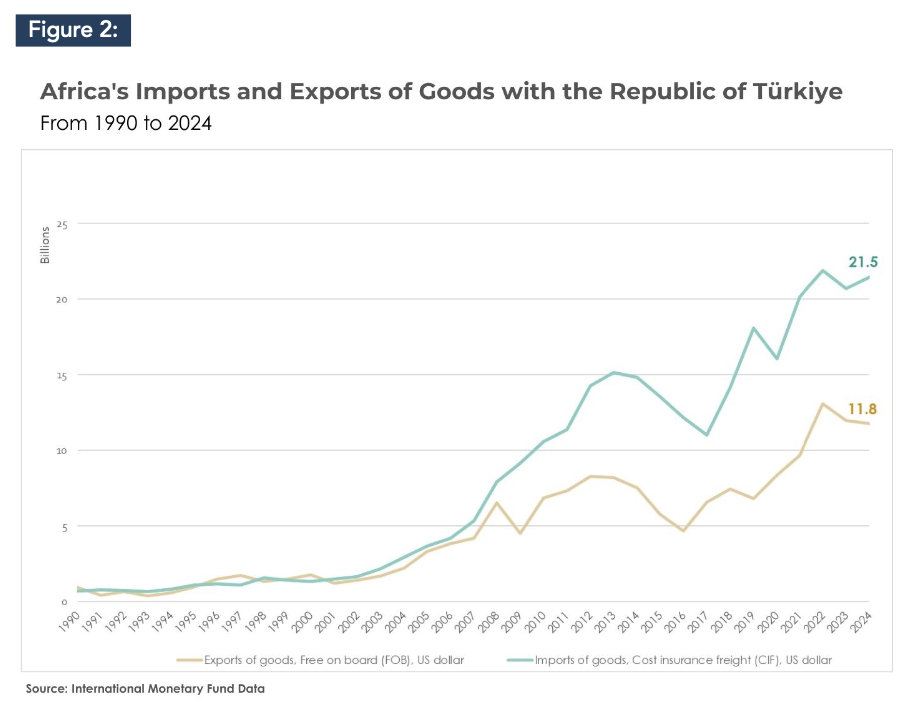

Türkiye’s ‘benevolent’ image served as an effective entry point into Africa, but subsequent expansion of trade, investment, and military cooperation demonstrates Türkiye’s interest-driven approach to the continent. Turkish interests include securing new markets, diversifying energy sources, and projecting political influence. One sign of Türkiye’s growing interests in Africa is the exponential growth of trade relations. Türkiye’s total trade volume with African countries increased from $5.4 billion in 2003 to $34.5 billion in 2021[19]. As the figure below shows, Africa imported $21.5 billion of goods from Türkiye in 2024, compared to $730 million in 1990.

In addition to economic relations, Türkiye has increased security and defense cooperation with African countries, building longer-term strategic bonds. Türkiye’s policy includes arms exports, military training support, counterterrorism initiatives, and institutional cooperation. While Türkiye’s focus centered more on countries such as Libya and Somalia in the past, Türkiye’s outreach is spreading wider on the continent today. In 2017, Türkiye established Ankara’s largest overseas base, Camp TURKSOM in Mogadishu, Somalia. A few months later, Türkiye acquired a 99-year lease over Suakin Island in Sudan for military use, under the premise that Türkiye would “restore and make it worthy of its historical glory,” according to Erdogan[20].

Building a military base in Libya to protect the Government of National Accord (GNA) reflected Türkiye’s overlapping geopolitical interests in the eastern Mediterranean and the Northern African region. After signing a maritime deal in 2019, against the interests of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum’s members, Türkiye continues to engage in negotiations over gas and oil exploration in Libya[21]. This showed Türkiye’s aim of expanding its sphere of influence and the increasing salience of security as a core element of its foreign policy in Africa. In addition to its traditional interest in Northern Africa and the Horn of Africa, Ankara has also marked its footprint in the Sahel region. Following Chad’s termination of its defense accords with France on November 28, 2024, Türkiye is filling the vacuum as a security guarantor. In February 2025, the Turkish Armed Forces signed an agreement with Chad for two military bases, Abeche and Faya-Largeau, near the borders with Libya and Sudan.

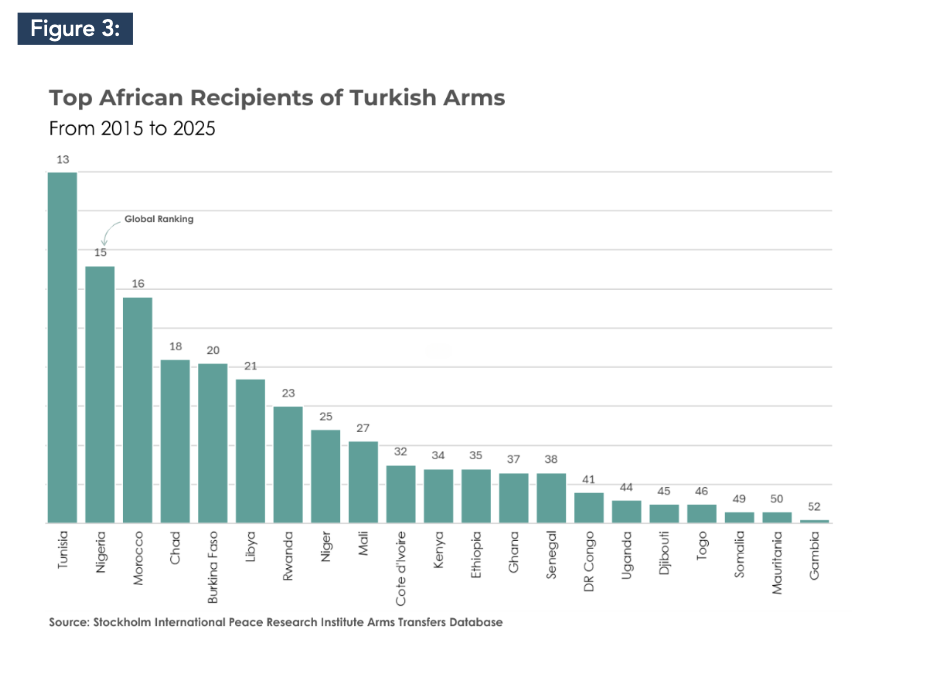

While countries including Italy, Germany, France, Russia, China, and the U.S. remain Africa’s biggest partners in terms of conventional arms sales, Türkiye is becoming a major arms supplier and gaining larger traction as a security partner. Many African countries now engage with non-Western powers such as Russia, China, India, and Türkiye for military training, intelligence sharing, and arms procurement, often seeking cost-effective solutions. In October 2021, Turkish President Erdogan visited Angola, Nigeria, and Togo, signing agreements on hydrocarbons, renewable energy, and mining. Many of these visits were accompanied by talks about the sale of Turkish drones, which are increasingly reconfiguring security apparatuses in Africa. Türkiye offers competitive prices for unmanned aerial vehicles, surveillance systems, and rifles, with a no-strings-attached policy. Many African countries are purchasing Turkish drones after witnessing their successful use in Syria, Ethiopia, Libya, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan. Türkiye has sold attack drones to Mali, Chad, Niger, and Burkina Faso, and has signed oil exploration deals with Senegal and Somalia. Ankara provides training to security forces in countries including Kenya, Ethiopia, and Uganda, to combat extremist groups and piracy.

In addition, Türkiye has systematized security cooperation by signing agreements to train militaries in Algeria, Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Gambia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Libya, Madagascar, Mali, Niger, Mauritania, Rwanda, Nigeria, Senegal, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia, and Tanzania[22]. Many more agreements have been signed for military and security cooperation at different levels, adding up to 30 African countries. Türkiye has 19 military attachés in various African countries.

In the post-Cold War context, Türkiye started playing an active role in peacekeeping and peacebuilding operations in its immediate region (the Balkans), but also in Africa (the 1993 UN Operations in Somalia (UNOSOM II); 1999 UN Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL); and the 1999 UN Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC)). In the 2000s, Türkiye’s joint security efforts with NATO and the UN in Africa contributed to peace efforts in Congo, the Central African Republic, Mali, Libya, Sudan, Somalia, and South Sudan. Today, Türkiye’s African security agenda diverges from NATO and the EU, with many of its initiatives being carried out independently. A prime example is Türkiye’s detachment from the EU in Somalia, where both carry out initiatives, separately, with little to no coordination between the two. Of the 18 missions and operations now being carried out worldwide under the EU’s Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP), 11 are taking place in Africa, and Türkiye has not participated in any of these operations[23].

This was not always the case. Historically, Türkiye experienced tensions with the West, such as the military embargo following its involvement in Cyprus in 1974. However, during the 2000s and into the 2010s, it remained a highly dependent security actor, primarily aligning with NATO and Western interests. Türkiye began seeking greater independence from the West as more contentious issues arose, including a national embargo following the Turkish intervention in northern Syria in 2019, disagreements over support for the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and tensions with the U.S. over the F-35 fighter project. According to Sıradağ, “Türkiye was overly engaged in NATO politics and thus failed to balance between its own national interests and NATO’s interests”[24]. The stalling of Türkiye’s EU accession process was a major factor in reducing policy alignment, allowing Ankara to act independently, occasionally in competition with European actors. Divergence from the West has allowed Ankara to act more flexibly and pragmatically in Africa, leveraging its positions as both a NATO member and a self-styled Global South actor. Türkiye’s approach emphasizes non-conditionality and comprehensive training directly linked to operational units, in contrast to the EU’s conditional, coordinated missions. Türkiye is positioning itself as an alternative to traditional European powers while capitalizing on African governments’ desire to diversify their external security partnerships. For middle powers or rising ‘new south’ countries like Türkiye, aligning with ideologically diverse partners opens greater opportunities to achieve strategic agreements[25].

Mediation as Middle-power Diplomacy

Mediation is a focal point of middle-power diplomacy. From attempts to mediate between Syria and Israel, the West and Iran, and Ukraine and Russia, Türkiye is capitalizing on its capacity as a ‘bridge’ to harbor leadership in the mediation domain. Türkiye has also been institutionalizing this role via frameworks in international organizations. On September 24, 2010, Türkiye formed the Group of Friends of Mediation with Finland to generate support for mediation and conflict prevention. The number of mediation efforts in sub-Saharan Africa reflects Türkiye’s doctrine of strategic depth. On December 11, 2024, Ethiopia and Somalia signed the Ankara Declaration, brokered by Türkiye, following a year of hostilities arising from tensions over the memorandum of understanding signed between Ethiopia and the breakaway region of Somaliland. Türkiye was able to find a delicate balance between two of its allies in the Horn of Africa to achieve this agreement.

After brokering a deal between Ethiopia and Somalia, Türkiye and Somalia signed in May 2025 a new hydrocarbon exploration and production agreement covering 16,000 km² of onshore territory. This builds upon a February 2024 offshore production-sharing agreement and ongoing seismic activities by the Oruç Reis vessel in Somalia’s maritime zones, with the 3D seismic survey reportedly 78% complete by May 2025. In a way, Türkiye’s footprint mimics that of countries including China, Russia, and the UAE. Turkish Airlines currently flies to 51 destinations in 39 countries in Africa, and their ‘2033 Strategy’ aspires for greater expansion, connecting Africa with Europe and the U.S. These interests reflect the fact that Türkiye’s ambitions extend beyond humanitarian and development aid.

Prior to the American mediation, Türkiye also sought to facilitate talks between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which was turned down by Kinshasa. Ankara also offered to mediate the dispute between Ethiopia and Sudan over the al-Fashaga region in 2020, but its efforts had little success. Türkiye also positioned itself as a mediator in the Sudanese conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which was welcomed by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. In 2021, Türkiye offered to mediate in the dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).

By acting as a mediator, Türkiye attempts to establish an image of a powerful actor and to build trust to create economic opportunities in trade, investment, and infrastructure projects. Because Türkiye lacks sufficient financial resources to act unilaterally the way major powers do, mediatory diplomacy enables Türkiye to appear as a peace promoter on the international stage. The foreign policy approach of Türkiye, shaped by the discourse and practice of the AKP in government, was described by former Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, as an “enterprising and humanitarian foreign policy”[26]. By using soft and hard power tools, Türkiye seeks to bolster its influence in Africa while contributing to the resolution of the continent’s conflicts.

Conclusion

Türkiye’s trajectory in Africa reflects the evolution of a middle power seeking to redefine its global role in an era of multipolarity. From soft to hard power projection, Ankara has cultivated a multilayered presence in Africa through the expansion of diplomatic missions, religious and educational institutions, humanitarian assistance, economic and trade partnerships, and security and defense cooperation. Its engagement in Africa reflects both continuity and dynamism in broader foreign-policy strategy. Carrying an Ottoman imperial legacy, Türkiye pursues a pragmatic, interest-driven approach in Africa, carving out spaces for niche diplomacy. Foreign policy shifts since the 2000s and geopolitical realignment between the West and the East explain Türkiye's ambitions to elevate its stature and bolster its power abroad. Pre-existing structures and imaginations of its national role as a ‘center state’ and an ‘Afro-Eurasian’ civilization further reinforce this vision. By framing its involvement through narratives of anti-colonialism and shared history, Türkiye strengthens its appeal to African leaders that are seeking to diversify their partnerships. Beyond simplistic West-East dichotomies, Türkiye’s foreign policy is complex, nuanced, and ever-evolving. Türkiye’s Africa policy, growing in the future, will depend on its ability to reconcile its narratives with reality, and its ambitions with its capabilities.

Bibliography

Abdulle, Abdulkarim Yusuf. “Economic Relations between Türkiye and Somalia: Prospects and Challenges.” A Peer-Reviewed Academic Journal for Somali Studies 7 (January 16, 2023): 64–86.

Adekunle Agbetiloye. “Turkey Plans Oil and Gas Exploration in Libya.” Business Insider Africa, April 21, 2025. https://africa.businessinsider.com/local/markets/turkey-plans-oil-and-gas-exploration-in-libya/y3lkgwn .

Akpınar, Pınar. “Turkey’s Peacebuilding in Somalia: The Limits of Humanitarian Diplomacy.” Turkish Studies 14, no. 4 (December 2013): 735–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2013.863448 .

Angey, Gabrielle. “The Gülen Movement and the Transfer of a Political Conflict from Turkey to Senegal.” Politics, Religion & Ideology 19, no. 1 (January 2, 2018): 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2018.1453256 .

Bilgic, Ali, and Daniela Nascimento. “Policy Brief Turkey’s New Focus on Africa: Causes and Challenges.” NOREF, September 1, 2014.

Cooper, Andrew Fenton. Niche Diplomacy : Middle Powers after the Cold War. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan ; New York, 1997.

Daily Sabah. “African Students Shape Their Future through Education in Türkiye.” Daily Sabah, March 14, 2025. https://www.dailysabah.com/turkiye/african-students-shape-their-future-through-education-in-turkiye/news .

Donelli, Federico. Turkey in Africa. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021.

Göktuğ Sönmez. A Neoclassical Realist Approach to Turkey under JDP Rule. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020.

HOLBRAAD, CARSTEN. “The Role of Middle Powers.” Cooperation and Conflict 6, no. 2 (1971): 77–90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45082994 .

hurriyet.com.tr. “‘Dünya 5’Ten Büyüktür’ Kampanya Oldu.” Hurriyet.com.tr. hurriyet.com.tr, September 25, 2014. https://www.hurriyet.com.tr/dunya/dunya-5-ten-buyuktur-kampanya-oldu-27276792 .

Ishmael, Len. “The New South in a Multipolar World Multi-Alignment or Fence Sitting?” Policy Center for the New South: Policy Paper 16/23, October 2023.

Jakub Wódka. “Turkey’s Middlepowermanship, Foreign Policy Transformation and Mediation Efforts in the Russia-Ukraine War.” Studia Europejskie (Warszawa) 2023, no. 4 (December 15, 2023): 215–33. https://doi.org/10.33067/se.4.2023.12 .

Joost Jongerden. The Routledge Handbook of Modern Turkey. London ; New York, Ny: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2021.

Kutlay, Mustafa, and Ziya Öniş. “Understanding Oscillations in Turkish Foreign Policy: Pathways to Unusual Middle Power Activism.” Third World Quarterly 42, no. 12 (October 16, 2021): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1985449 .

Maarifschool.org. “Turkey’s Maarif Foundation Is an Excellent Example of Turkish Aid,” 2020. https://gh.maarifschool.org/news/turkeys-maarif-foundation-is-an-excellent-example-of-turkish-aid .

Massicard, Elise. “Une Décennie de Pouvoir AKP En Turquie : Vers Une Reconfiguration Des Modes de Gouvernement ?” Les Études du CERI 205, 2014.

Melis, Nicola. “The Ottoman Africa and the Ottomans in Africa: An Introduction.” Eurasian Studies 21, no. 2 (June 14, 2024): 143–50. https://doi.org/10.1163/24685623-20230150 .

New African Magazine. “Suakin Rises from the Dead - New African Magazine,” April 2018. https://newafricanmagazine.com/21163/ .

ÖzerdemAlpaslan, and Matthew Whiting. “The Routledge Handbook of Turkish Politics.” In Turkey as an Emerging Global Humanitarian and Peacebuilding Actor. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “TÜRKİYE-AFRICA RELATIONS / Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs.” www.mfa.gov.tr, 2022. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye-africa-relations.en.mfa .

Sıradağ, Abdurrahim. “Understanding Türkiye’s New Defense and Security Policy towards Africa: New Dynamics, and New Approaches.” Turkish Journal of African Studies 2, no. 1 (2025): 19–32.

Tepperman, Jonathan, and Abdullah Gul. “Turkey’s Moment: A Conversation with Abdullah Gul.” Foreign Affairs 92, no. 1 (2013): 2–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/41720998 .

The Economist. “Ottoman Dreaming.” The Economist, March 25, 2010. https://www.economist.com/europe/2010/03/25/ottoman-dreaming .

Ünal, Ali. “Maarif Foundation Head: We Aim to Offer an Education That Reflects Turkish Vision, Promote Turkish Language.” Daily Sabah, February 12, 2017. https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/2017/02/13/maarif-foundation-head-we-aim-to-offer-an-education-that-reflects-turkish-vision-promote-turkish-language .

Yaşar, Nebahat Tanrıverdi. “Unpacking Turkey’s Security Footprint in Africa Trends and Implications for the EU .” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, June 30, 2022. https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2022C42/ .

Zakaria, Fareed. “Facing a Post-American World.” New Perspectives Quarterly 25, no. 3 (June 2008): 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5842.2008.00993.x .

[1] Carsten Holbraad, “The Role of Middle Powers,” Cooperation and Conflict 6, no. 2 (1971): 77–90, https://www.jstor.org/stable/45082994. A middle power is defined as a state occupying an intermediate position in a hierarchy based on power, a country much stronger than the small nations, though considerably weaker than the principal members of the states system.

[2] Göktuğ Sönmez, A Neoclassical Realist Approach to Türkiye under JDP Rule (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020).

[3] Mustafa Kutlay and Ziya Öniş, “Understanding Oscillations in Turkish Foreign Policy: Pathways to Unusual Middle Power Activism,” Third World Quarterly 42, no. 12 (October 16, 2021): 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1985449.

[4] The World is Bigger than Five hurriyet.com.tr, “‘Dünya 5’Ten Büyüktür’ Kampanya Oldu,” Hurriyet.com.tr (hurriyet.com.tr, September 25, 2014), https://www.hurriyet.com.tr/dunya/dunya-5-ten-buyuktur-kampanya-oldu-27276792.

[5] The rise of the rest is a concept developed in: Fareed Zakaria, “Facing a Post-American World,” New Perspectives Quarterly 25, no. 3 (June 2008): 7–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5842.2008.00993.x.

[6] ‘Strategic Depth’ refers to Ahmet Davutoğlu’s book Stratejik Derinlik (Strategic Depth).

[7] Jakub Wódka, “Türkiye’s Middlepowermanship, Foreign Policy Transformation and Mediation Efforts in the Russia-Ukraine War,” Studia Europejskie (Warszawa) 2023, no. 4 (December 15, 2023): 215–33, https://doi.org/10.33067/se.4.2023.12.

[8] Federico Donelli, Türkiye in Africa (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021).

[9] Jonathan Tepperman and Abdullah Gul, “Türkiye’s Moment: A Conversation with Abdullah Gul,” Foreign Affairs 92, no. 1 (2013): 2–7, https://doi.org/10.2307/41720998.

[10] The Economist, “Ottoman Dreaming,” The Economist, March 25, 2010, https://www.economist.com/europe/2010/03/25/ottoman-dreaming.

[11] Nicola Melis, “The Ottoman Africa and the Ottomans in Africa: An Introduction,” Eurasian Studies 21, no. 2 (June 14, 2024): 143–50, https://doi.org/10.1163/24685623-20230150.

[12] Abdulkarim Yusuf Abdulle, “Economic Relations between Türkiye and Somalia: Prospects and Challenges,” A Peer-Reviewed Academic Journal for Somali Studies 7 (January 16, 2023): 64–86.

[13] Andrew Fenton Cooper, Niche Diplomacy: Middle Powers after the Cold War (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan; New York, 1997).

[14] Pınar Akpınar, “Türkiye’s Peacebuilding in Somalia: The Limits of Humanitarian Diplomacy,” Turkish Studies 14, no. 4 (December 2013): 735–57, https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2013.863448.

[15] Gabrielle Angey, “The Gülen Movement and the Transfer of a Political Conflict from Türkiye to Senegal,” Politics, Religion & Ideology 19, no. 1 (January 2, 2018): 53–68, https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2018.1453256.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ali Ünal, “Maarif Foundation Head: We Aim to Offer an Education That Reflects Turkish Vision, Promote Turkish Language,” Daily Sabah, February 12, 2017, https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/2017/02/13/maarif-foundation-head-we-aim-to-offer-an-education-that-reflects-turkish-vision-promote-turkish-language.

[18] “Türkiye’s Maarif Foundation Is an Excellent Example of Turkish Aid,” Maarifschool.org, 2020, https://gh.maarifschool.org/news/Türkiyes-maarif-foundation-is-an-excellent-example-of-turkish-aid.

[19] Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “TÜRKİYE-AFRICA RELATIONS / Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” www.mfa.gov.tr, 2022, https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye-africa-relations.en.mfa.

[20] “Suakin Rises from the Dead - New African Magazine,” New African Magazine, April 2018, https://newafricanmagazine.com/21163/.

[21] The members include Greece, Cyprus, France, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Palestine, and Italy; the observer role of the UAE was reportedly vetoed by Palestine.

[22] Nebahat Tanrıverdi Yaşar, “Unpacking Türkiye’s Security Footprint in Africa Trends and Implications for the EU,” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, June 30, 2022, https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2022C42/, 2.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Abdurrahim Sıradağ, “Understanding Türkiye’s New Defense and Security Policy towards Africa: New Dynamics, and New Approaches,” Turkish Journal of African Studies 2, no. 1 (2025): 19–32.

[25] Len Ishmael, “The New South in a Multipolar World Multi-Alignment or Fence Sitting?” (Policy Center for the New South: Policy Paper 16/23, October 2023).

[26] Joost Jongerden, The Routledge Handbook of Modern Türkiye (London; New York, Ny: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2021).