Publications /

Opinion

This Opinion was originally published in Project Syndicate

However politically convenient narratives about the United States "abandoning" manufacturing may be, the reality is more complex and less gloomy than many assume. In fact, US manufacturing has not disappeared, but it did internationalize as American companies pursued higher-value opportunities at home.

WASHINGTON, DC – Conventional wisdom holds that the United States has undergone a massive deindustrialization in recent decades, with the country’s manufacturing sector supposedly withering as it lost ground to China. This narrative has fueled debates about industrial policy, economic nationalism, and the reshoring of manufacturing production. But what if it is only partly true? What if, instead of disappearing, American industry simply changed its address?

A closer look at the data suggests that what the US lost in domestic manufacturing, it may have gained in global productive presence. Rather than collapsing, American industry internationalized.

True, manufacturing as a share of US GDP has declined. In 1970, the sector accounted for about 24% of the American economy; by 2023, it represented less than 11%. Industrial employment also fell sharply – by nearly seven million jobs since the peak in the 1970s.

These figures have supported the idea that the US “abandoned” its industry. But two additional points should be noted. First, as technology has evolved, manufacturing employment per unit of output shrunk in many countries. For example, Germany’s continued success in manufacturing was nevertheless accompanied by declining employment.

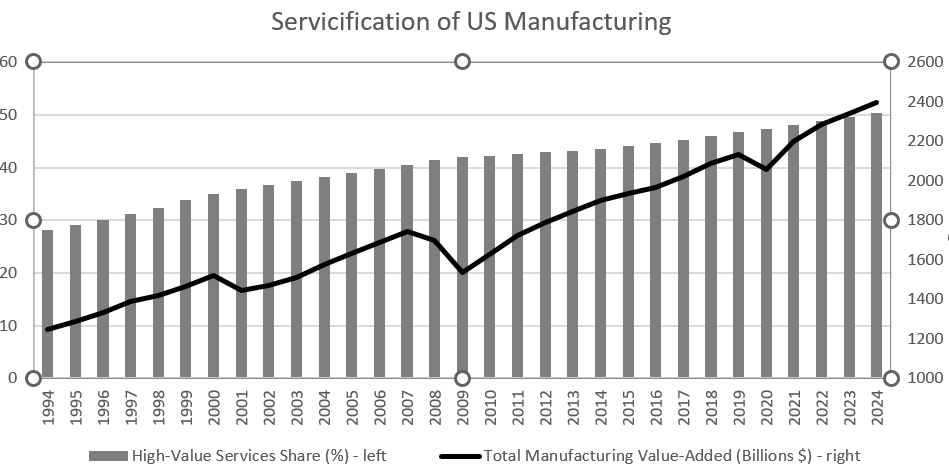

Second, US real (inflation-adjusted) manufacturing value added (the difference between input costs and the value of the net output) has been rising over the past four decades, even as factory jobs declined. The sector’s composition has been characterized by a rising share of higher-value goods, like advanced technologies and aerospace products, manufactured with fewer workers and higher levels of automation.

During this period, China became a manufacturing powerhouse. In 2023, it was the world’s largest industrial producer, with estimated value added reaching $4.6 trillion – almost double America’s $2.8 trillion. But to conclude that this signals the decline of American industrial leadership overlooks a crucial fact: The data used here – such as industrial value added – are calculated on the basis of national territory, which means that they measure only what is physically produced within a country’s borders. This is akin to the distinction between GDP and GNP but applied to manufacturing.

The problem with this method is that it misses a major feature of the twenty-first-century economy: the internationalization of production chains. Large American companies maintain extensive production networks abroad, whether through subsidiaries, joint ventures, or contracts with local suppliers. This production is often shaped, overseen, and controlled by engineers, designers, and executives in the US, even as it physically occurs in other parts of the world.

So, American manufacturing did not disappear, it relocated. American factories operating in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere are supplying local and global markets and integrating global value chains.

Data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) indicate that, by 2024, the stock of US direct investment in manufacturing abroad was about $1.1 trillion, while the corresponding figure for China was estimated to be around $200 billion. These overseas industrial operations don’t appear in national accounts. By measuring only what is produced domestically, we underestimate the true scale of US-controlled manufacturing. In fact, BEA statistics suggest that if we include overseas production controlled by US companies, the “global manufacturing value” of the US could reach $3.9 trillion – much closer to China’s total. The high relevance of US manufacturing abroad is supported by different data sources and may help explain why US stock markets suffered less than US-based workers.

Moreover, not all of China’s exports are entirely “Made in China.” According to OECD data, part of the value of Chinese exports corresponds to inputs imported from third countries, which could mean that less than 65% of the value of Chinese manufactured exports is generated within China. In the case of the US, this share is around 80%, indicating that the US captures more value added in the stages under its control.

Some of the confusion about US “deindustrialization” also arises from how we measure sectoral GDP. A significant share of the value added in industrial production – especially high-value activities – is classified as “services.” Logistics, research and development, engineering, software, patents, branding, distribution, design, and supply-chain management (among others) are fully integrated into manufacturing, but are counted under a different economic category.

So, when a company like Boeing coordinates production using global suppliers, most of the value added in the US is not recorded as manufacturing, even though it is deeply tied to it. Aggregating manufacturing capabilities with service functions directly tied to the sector implies a US industrial footprint that appears to surpass China’s.

The real question, then, is not just how much is produced and where (US President Donald Trump’s obsession). It is about who controls and captures value from industrial supply chains. From this perspective, the US remains highly industrialized, albeit through a sophisticated and globalized business model.

This reality has important implications for debates about reindustrialization, trade, tariffs, and industrial policy. The issue is not just “bringing factories back,” but understanding who is in control, where value is generated, and how production networks can be organized in more resilient, efficient, and sustainable ways.

However politically convenient the deindustrialization narrative may be, the reality is more complex and less gloomy than many assume. The US may have lost factories, but it did not lose industrial capacity. Its capacity simply became transnational.

At a time of geopolitical realignment, trade tensions, and the energy transition, understanding this nuance is essential. The future of manufacturing is not only about factory floors, which are increasingly populated by robots. More importantly, it is about where, how, and with whom to produce, and about who captures the resulting profits and influence.

Efforts to reshore labor-intensive parts of the supply chain through reshoring policies and tariffs have had minor impacts in US manufacturing. The sector’s renaissance would come at the expense of higher-value activities, because US businesses will need to reallocate limited labor resources. Low-income households that currently benefit from low-cost imported goods will face higher prices, with or without the establishment of domestic supply chains. Trying to recreate the manufacturing sector of old will not only fail; it will make Americans poorer.