Publications /

Opinion

The United States has suffered more COVID-19 casualties than any other country and continues to report large numbers of new cases and deaths, and – as evident recently in stock markets – investors remain extremely sensitive to the epidemic’s shifting trends. As every state reopens, including most recently the New York epicenter, the fates of the American economy and of the global economy depend on whether the United States has put the worst of the epidemic behind it, or whether it will be forced to reclose in the face of a resurgence of infections. We assess the risks by drawing on the record of countries that appear to be reopening successfully so far.

Our comparison group includes Austria and Italy, which reopened early—respectively in mid-April and early May—when death rates and cases were steadily declining. In those countries, there has been no evidence of a resurgence of infections or deaths. We choose Italy because it was the country hit hardest by the pandemic in its earlier phases, it entered its worst period far earlier, and it operated a severe lockdown. Austria was the earliest reopener in Europe and suffered a relatively mild episode. We also include Sweden in the comparison group. Sweden is especially interesting has it eschewed a national lockdown altogether and now reports cases and death rates among the highest in Europe. European countries such as Austria, Italy and Sweden are Western democracies that are among the closest to the United States in income level. Asian countries, including Australia, China, Japan, Korea, and New Zealand, have seen far less severe medical effects from the pandemic than Europe and the United States.

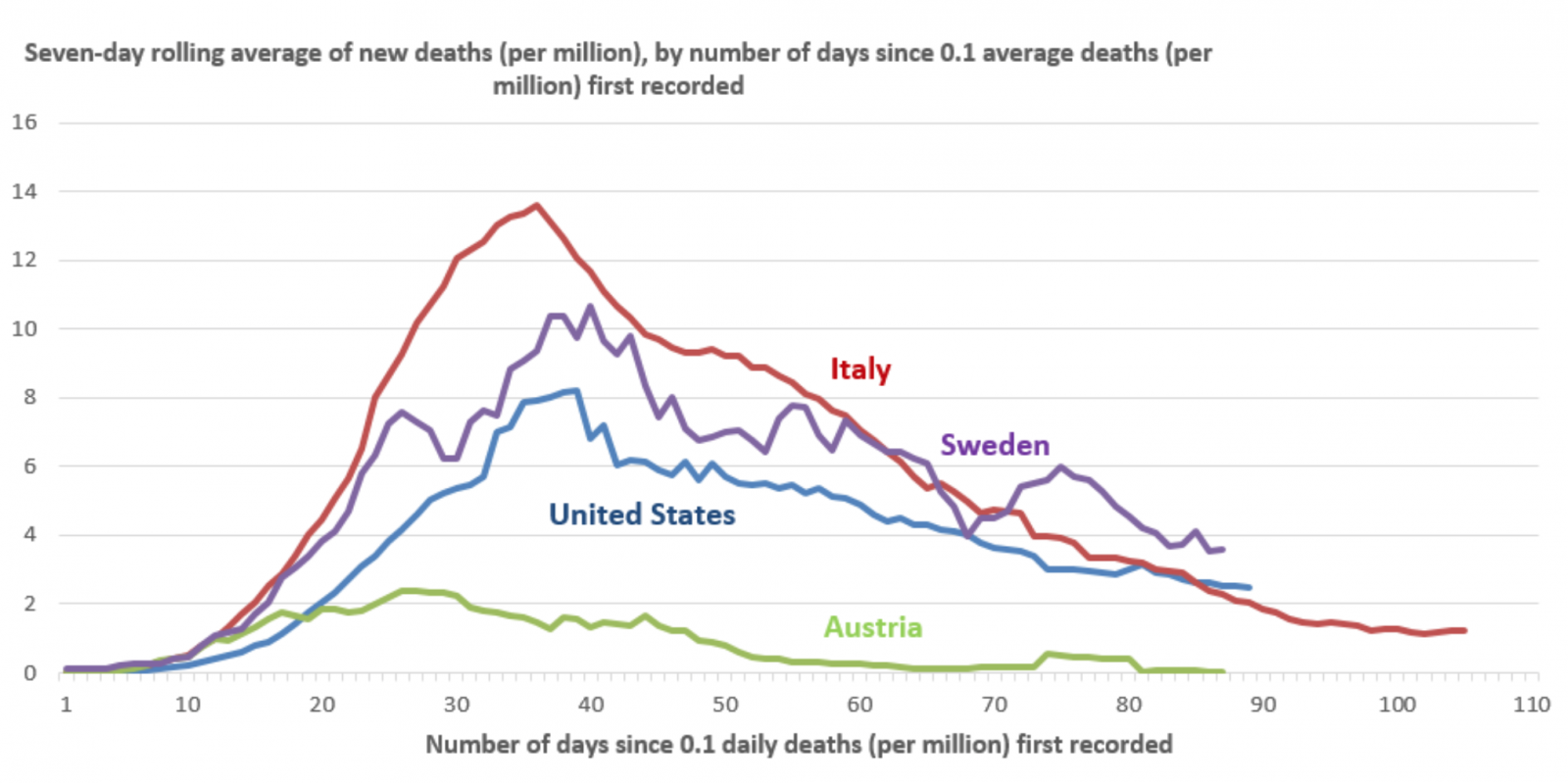

The epidemic in the United States crossed a critical initial threshold at the same time as Austria and Sweden and about three weeks later than Italy, as seen in Figure 1 (inspired by the very helpful presentation of Covid-19 data in the Financial Times). At its peak in mid-April, the death rate in the United States was around six per million, far lower than in Italy, lower than in Sweden, and far higher than Austria. The death rate in the United States continues to decline and is now near two per million, whereas Italy’s is now approaching one and Austria’s close to zero.

Figure 1: Seven-day rolling average of new deaths (per million), by number of days since 0.1 average deaths (per million) first recorded for countries

Source: Our World in Data

This simple comparison of death rates makes it clear that the United States—where reopening began in the state of Georgia in the third week of April—sees an improved situation but remains more exposed to the epidemic than Austria and Italy, and nearly all other EU nations, where the epidemic is waning across the board, with Sweden the exception. However, the U.S. is a continental economy composed of more than 50 states and territories, several of which have populations larger than that of some nations. Given the size and diversity of the United States, and the highly differentiated impact of the pandemic on its different localities, the risk of reopening cannot be assessed without reference to individual states. Here we will focus mainly on the six states with the largest populations, namely California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas, which account for about 45% of U.S. GDP and over 33% of the U.S. population. Our reasoning is that failure to control the epidemic in one or more of these large states could trigger a renewed national or partial lockdown that would have a severe effect on the national economy.

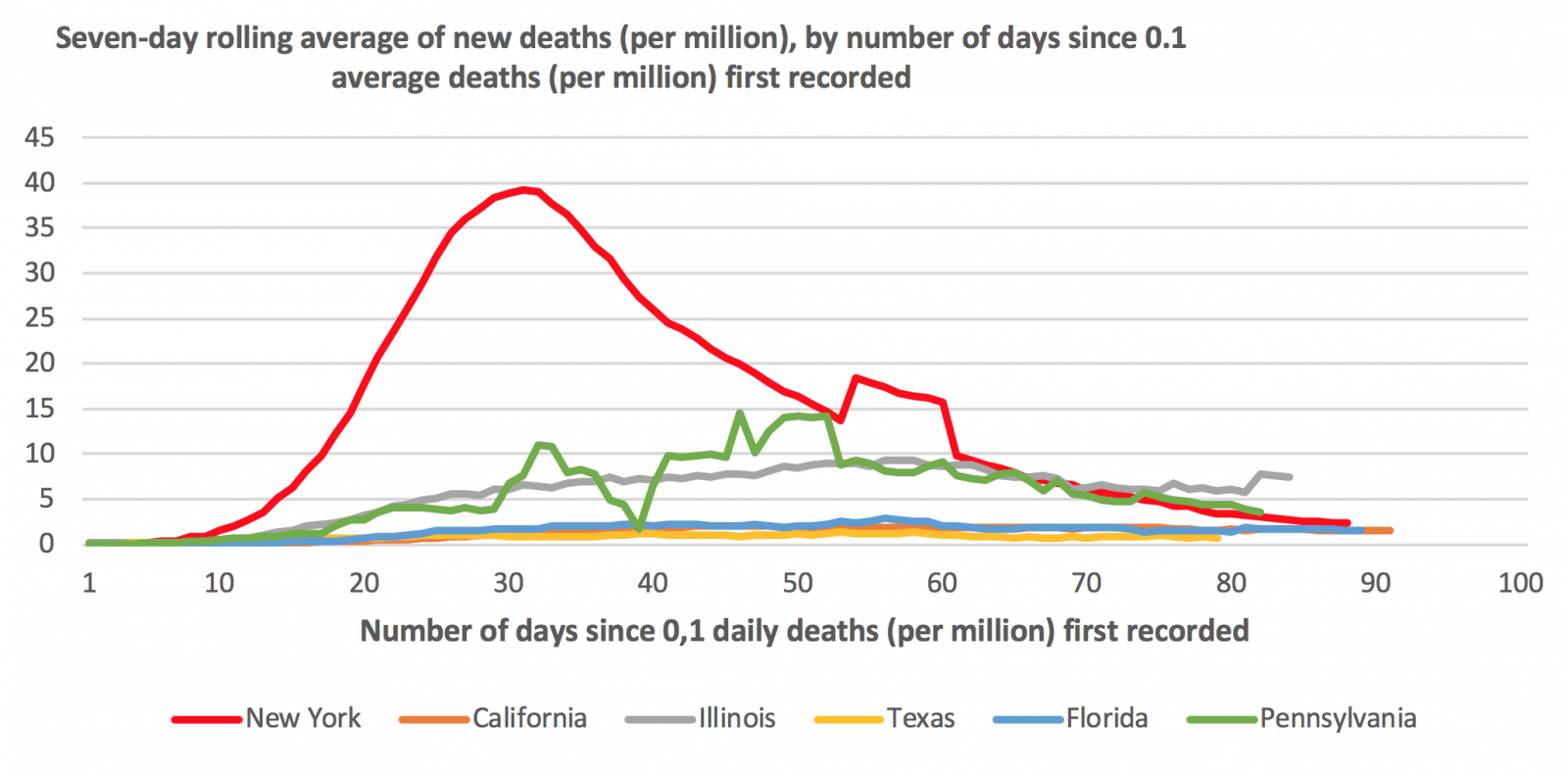

Figure 2: Seven-day rolling average of new deaths (per million), by number of days since 0.1 average deaths (per million) first recorded for states

Source: Covid Tracking Project

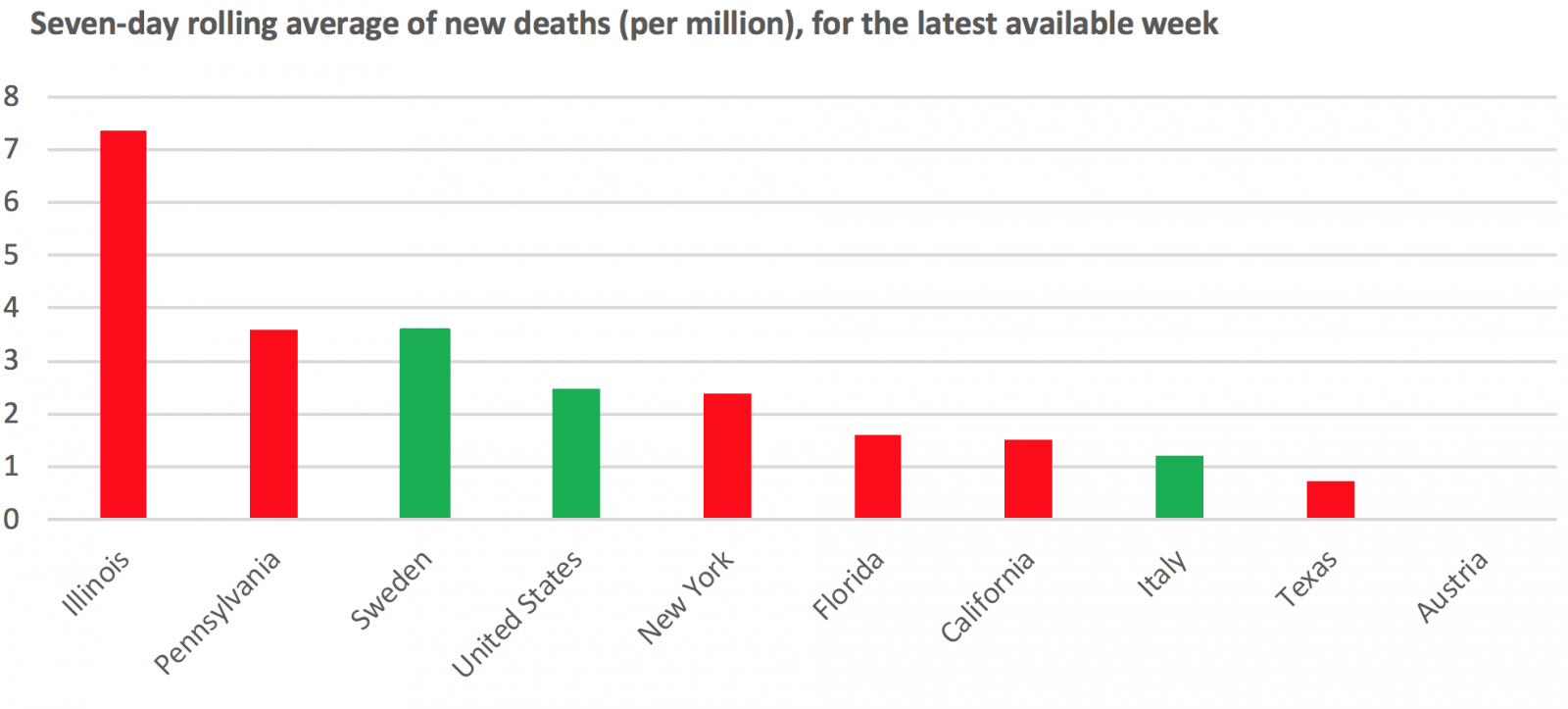

Figure 3: Seven-day rolling average of new deaths (per million), for the latest available week:

Source: Our World in Data, Covid Tracking Project

The comparisons in Figure 2 and 3 above suggest that the large states fall into three groups: New York stands on its own as exhibiting an epidemic pattern very similar to that of Italy, including a high and sharply declining number of new cases (not shown) and deaths. If the Italian experience is a guide, there is little reason to expect a resurgence of the epidemic in New York in the coming months, even as it gradually reopens. Similar patterns to New York can be seen in other smaller states in the north-east U.S. worst hit by the epidemic, such as New Jersey and Connecticut.

The second group of states consists of California, Florida, and Texas, whose epidemic patterns are perhaps closest to that of Austria, characterized by a low number of new cases (not shown) and deaths adjusted for population. However, these states differ in significant respects from Austria and Italy, as they continue to report a rising number of cases, stable numbers of new deaths, and still high shares of positive tests.

The share of positive tests is an important and sometimes overlooked indicator. Since tests are usually only carried out on patients who are suspected of having contracted the disease, the share of positive tests can indicate an upper bound estimate of the prevalence of the disease in the wider population. Test positivity is now minuscule in Austria and Italy, well under 0.5% and low in Sweden, less than 1%, but—except for New York where it is close to 1%—it is far higher in the other large U.S. states. Test positivity is over 5% in California, Florida, and Texas, and over 10% in Pennsylvania and Illinois. Based on this indicator, it is highly likely that the virus remains far more widespread across these states than in Sweden, Austria, and Italy, even if test positivity is measured at the time that the latter two started reopening.

What can be said with some confidence is that, because the number of new cases and deaths in Florida, California, and Texas is low— well below the incidence in Italy at the time of reopening—there will be time for governments to react should the indicators point in the wrong direction. These states also presently have sufficient hospital capacity and, given their relatively low number of cases, probably have the ability to identify clusters of cases, trace contacts and treat patients. However, if there continues to be rise in cases – as has been seen recently in all three – that situation could change quite quickly. Several states in the south and west of the United States have epidemic patterns that resemble those of California, Florida, and Texas, though most are not seeing a rise in cases, including Georgia, the first state to open.

The third group of states, consisting of Illinois and Pennsylvania, is the most problematic in our view. These are states where the number of infections, deaths, and shares of positive cases remain high and there is no clear trend of improvement in death rates. The death rate in Illinois is 7.4 per million per day (seven day moving average). To put that rate in perspective, it is double the rate in Sweden, where the government’s policy of no-lockdown has come under increasingly strong criticism. The number of new cases in Illinois and Pennsylvania is stable or on a gentle downward path but remains at levels where it is difficult to believe that a systematic policy of testing, tracking and treatment can work without disproportionate expenditure of resources. Other large states in the mid-west and north-east, including Ohio and Massachusetts, exhibit similar epidemic patterns to Illinois and Pennsylvania.

We conclude from this short review that the risk of a reversal of reopening policies in one or more large U.S. states, most notably – but not only - in the third group, remains significant.

Still, it is difficult to imagine that a resurgence of COVID-19 in one or more states would prompt a return to a nationwide lockdown in the United States. Control of the disease is being carried out in highly decentralized and localized fashion, led by state governors who often defer to leaders in individual cities or counties where situations differ markedly. A return to a national lockdown would be seen as economically disastrous, and, in 2020, the year of a fateful election, such a reversal would be politically calamitous for incumbents. A more likely scenario is the acceptance of increased death rates and of selective tightening of restrictions in the localities/groups worst affected. Depending on the prevalence of these localized outbreaks the effect on US consumer and investor confidence could be severe, delaying -but probably not aborting – the economic recovery in the United States and across the world.

[1] Mahmoud Arbouch provided helpful research assistance.