Publications /

Opinion

Last week marked my twenty-third consecutive week attending the World Bank and IMF Spring Meetings in Washington, DC. While I no longer participate in the official sessions, I continue to be invited to the many side conventions and debates that surround them.

A key moment is always the release of the IMF's World Economic Outlook report. This year, it drew particular attention due to curiosity about how the institution would project the impacts of the tariff war initiated by Trump’s second administration.

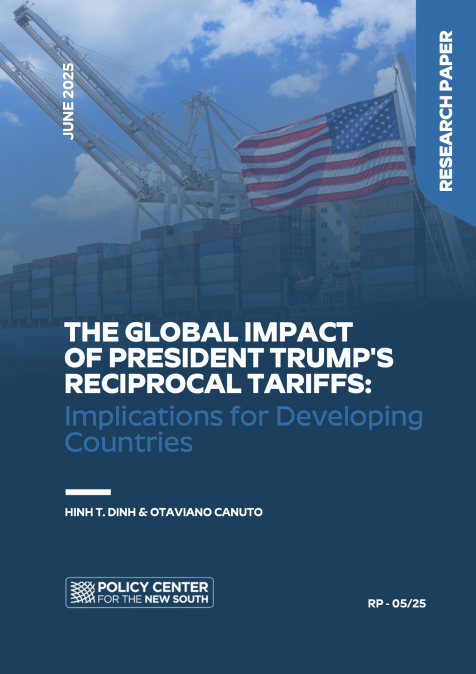

The IMF downgraded its global growth forecast by half a percentage point to 2.8% for this year and lowered its 2026 forecast to 3% (Figure 1). This marks a slowdown from the 3.3% growth rate in 2024, with the Fund warning of a “major negative shock” from rising trade barriers. The forecast factored in only the tariff announcements from the U.S. and retaliatory measures from other countries between February 1 and April 4—prior to Trump’s announcement of a 90-day pause on most of his so-called “reciprocal tariffs,” alongside an increase in tariffs on China.

The Fund cut its U.S. growth forecast for 2025 to 1.8%—down from the previous projection of 2.7%—and to 1.7% for 2026. While this still positions the U.S. as the fastest-growing G7 economy for this year and next, it represents a clear decline from the 2.8% expansion recorded in 2024. The IMF also downgraded growth projections for all other G7 countries, as well as for other major economies, including China, India, Brazil, and South Africa.

China is expected to slow down, with the IMF forecasting 4% growth for both this year and next, down from 5% in 2024. Brazil’s real GDP growth forecast was reduced to 2% for both 2025 and 2026. Among G20 countries, only Turkey, Argentina, and Russia received upgraded growth projections.

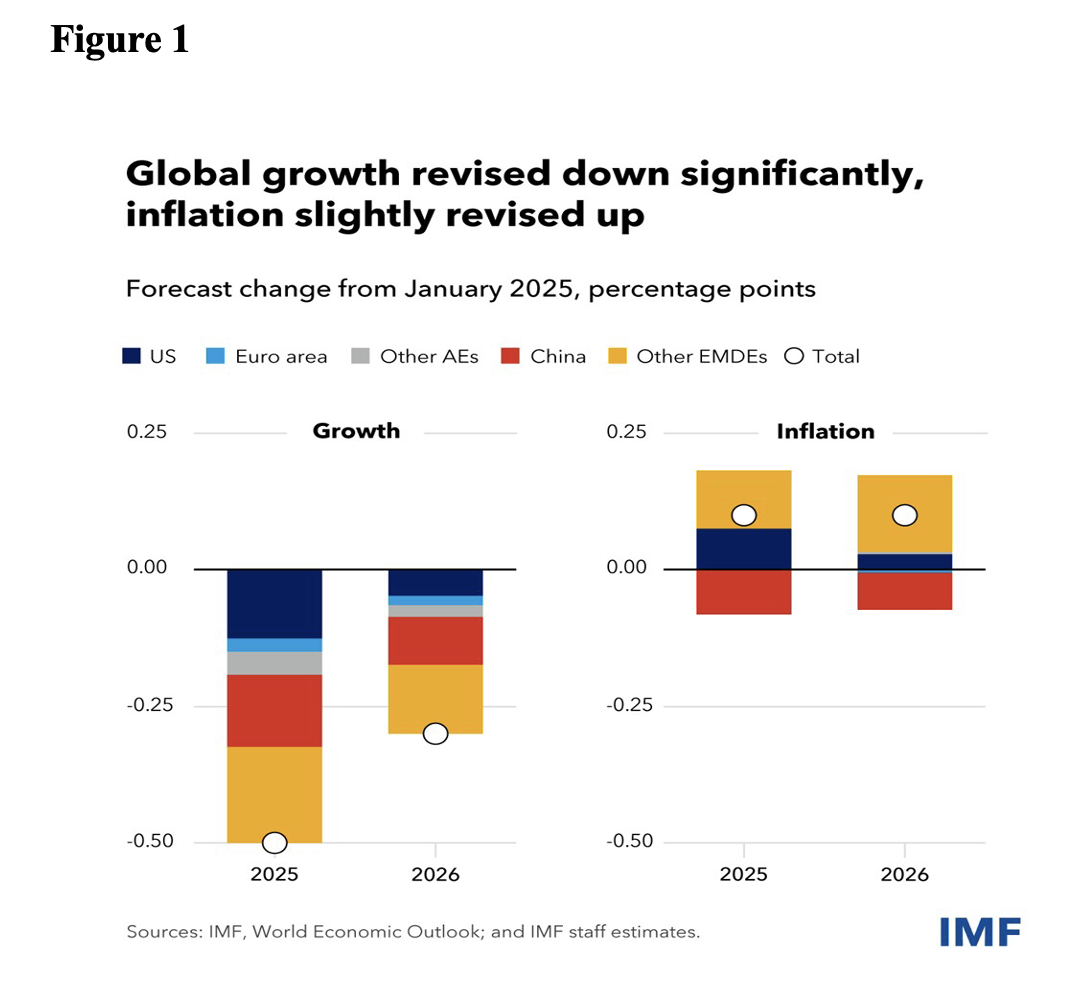

The IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report also attracted significant attention, particularly due to the financial market turbulence since early April. The report concluded that risks to markets have "increased significantly" since the White House’s tariff moves, with a selloff in U.S. equities and government debt contributing to a "tightening of financial conditions” (Figure 2).

The announcement of the “reciprocal tariffs” on April 2 had an immediate negative impact on stock markets. Starting on April 7, similar effects emerged in U.S. government bond markets. We began witnessing phenomena typically associated with emerging markets facing capital flight: yields on 10-year Treasury bonds rose while the dollar depreciated. Global portfolios visibly began shedding U.S. assets.

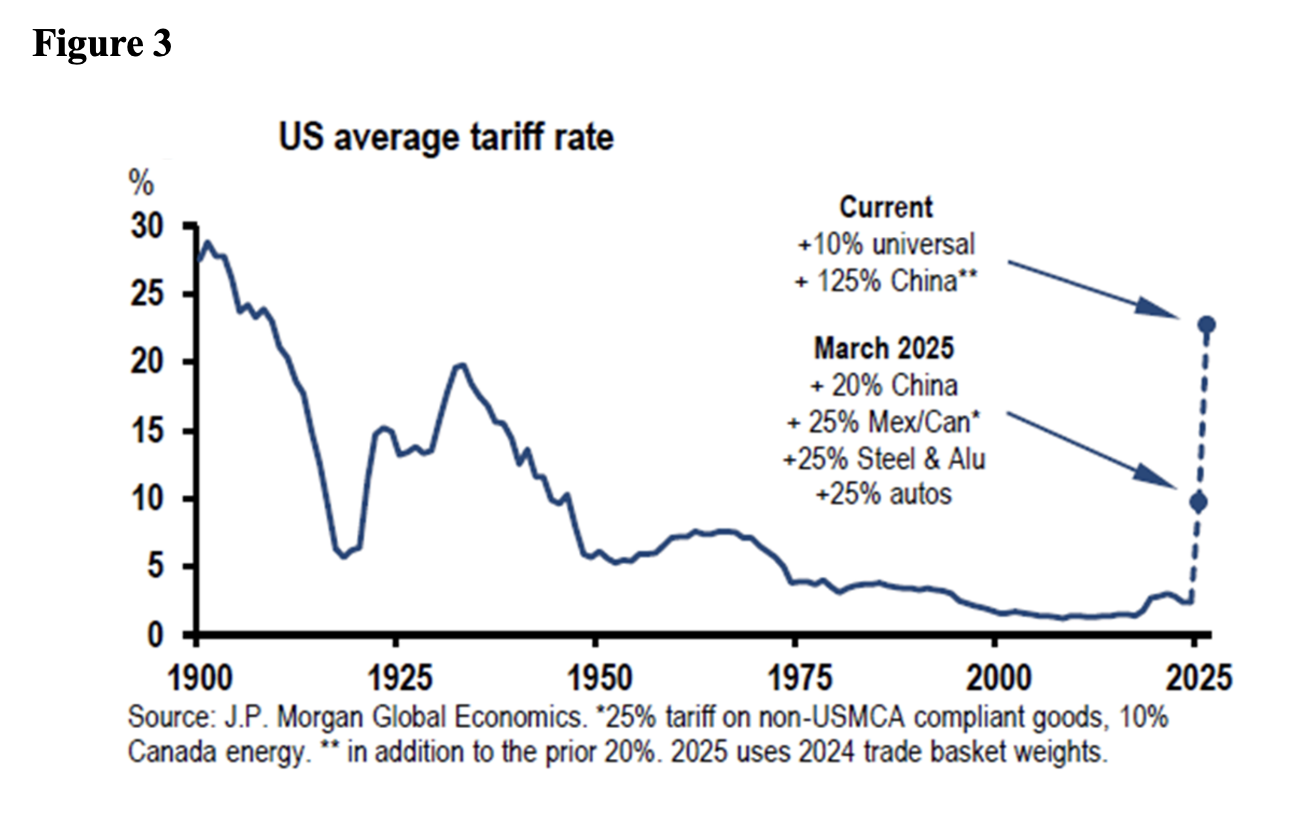

These market moves reflected a shift in perception about who holds influence over Trump’s trade policy. Until the April 2 announcement of the sweeping “reciprocal tariffs” (Figure 3), it was widely believed that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s perspective held sway—that Trump's tariffs were primarily “transactional” tools used for negotiation. This had been the case with Mexico during Trump’s first term and appeared to guide the initial approach toward Canada and Mexico during his second term.

The shock on April 2 marked a turning point, revealing that the dominant logic may now be pure protectionism, driven by the ascendancy of Howard Lutnick (Secretary of Commerce), Peter Navarro (Senior Counselor for Trade and Manufacturing), and Jamieson Greer (U.S. Trade Representative). In response, markets shifted their focus to the damaging real-economy and financial impacts underscored in the two IMF reports released last week.

It was no coincidence that the 90-day postponement of the “reciprocal tariffs”—even with the China-specific increases—occurred during Scott Bessent’s presence at the White House. The brief market relief that followed reflected renewed hope that the “transactional” approach might still prevail. However, turmoil in the bond markets was briefly reinforced by Trump’s threat to fire Federal Reserve Governor Jeremy Powell—a threat that was denied last Monday.

The escalation of tariffs and retaliatory measures from China appeared to catch the Trump administration off guard. Remarkably, the U.S. intensified its tariff war with China with little apparent preparation for the practical consequences—such as China’s current dominance in processing over 90% of critical minerals and magnets essential for digital products.

A high-stakes bluff—a kind of geopolitical poker game—now seems to be unfolding between the U.S. and Chinese governments. Trump and Bessent continue to speak of negotiations, while the Chinese maintain that talks can only begin once the U.S. rolls back specific new measures targeting China.

On Tuesday, April 22, Secretary Bessent stated at a JPMorgan-hosted conference that he hoped the two countries would eventually reach an agreement, adding that a trade war with China was “unsustainable.”

On Friday, April 25, reports emerged that China’s Ministry of Commerce was reviewing sectors impacted by Beijing’s 125% tariffs on U.S. products, according to Michael Hart, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in China. Meanwhile, although Donald Trump claimed Chinese President Xi Jinping had “called” him, Beijing denied that any negotiations to ease trade tensions between the world’s two largest economies had begun.

Another hot topic last week was the Trump administration’s evolving relationship with multilateral institutions. One of Trump’s first executive orders mandated a review of U.S. engagement with these institutions, with a report due in August. Last year, the influential conservative think tank, the Heritage Foundation, even proposed a U.S. withdrawal from the Bretton Woods institutions.

At a side event during this week’s IMF and World Bank Spring Meetings—hosted by the Institute of International Finance—Secretary Scott Bessent stopped short of calling for an exit. However, he emphasized the need to tie U.S. contributions to a shift in institutional priorities. He criticized the IMF and World Bank for “mission drift,” urging them to move away from “extensive and unfocused agendas” such as climate change and gender issues.

Returning to last week’s IMF reports, they also outlined more optimistic scenarios, contingent on successful negotiations between the U.S. and its major trading partners that could lead to tariff reductions. According to Tobias Adrian, director of the IMF’s Monetary and Capital Markets Department, although the negative effects of tariffs have already been “somewhat priced in,” equity and bond prices could “certainly” fall further if negotiations fail. The outlook is clear: either a path towards compromise or the looming prospect of further stress and downgrades.

Let’s hope for the best after such a spring of tariff regret.