Publications /

Opinion

We have previously discussed how, between March 2020, when the financial shock caused by COVID-19 occurred, and the end of August, the stock and corporate debt markets in the United States performed extraordinarily, despite gloomy prospects on the real side of the economy. The decline in technology stock prices in September ended up taking the equivalent of a month from gains starting in April, but prices remain high.

On the basis of such a ‘disconnect from reality’ in financial markets, we pointed to the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) interest rate cuts and liquidity flooding, which were done to avoid a dramatic credit crunch, massive bankruptcy waves, and even greater unemployment than what happened. Other central banks of advanced economies—the Eurozone, Japan, the United Kingdom—acted similarly. According to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the central banks in these countries have, since January, collectively created something around $3.8 trillion in new money, most of which ended up in government bonds yielding almost zero. Admittedly, such an attitude on the part of central banks was one of the factors that prevented an economic catastrophe even greater than that which has occurred.

In fact, the response of those central banks to the COVID-19 shock was the continuation of something already underway in the previous decade. It is true that, particularly in the case of the Fed, this time there was an extension of the set of tools, through the creation of credit lines and liquidity support in addition to banks, the basic vehicle for the operation of monetary policy.

But it is also a fact that, since the global financial crisis in 2008-2009, those central banks have resorted to quantitative easing (QE) policies, meaning direct acquisition of assets by central banks to reinforce reductions in interest rates. In the beginning, the objective was to prevent the global financial crisis from unfolding into a repeat of the Great Depression of the 1930s; however, the temporary appeal became more prolonged, in part because of the difficulties of getting out of it and returning to the ‘old normal’. The “unconventional has become conventional”, as Claudio Borio, from BIS, has said.

The abundance of liquidity has not been followed by inflation acceleration. However, concerns have been raised about the possibility of unviable companies and projects escaping closure—becoming ‘zombies’—or asset prices being overvalued, with the emergence of new bubbles, reflecting low interest rates and extremely favorable financial conditions. The policy of central banks came also to be seen by some as favoring asset holders, that is, the upper part of the income pyramid.

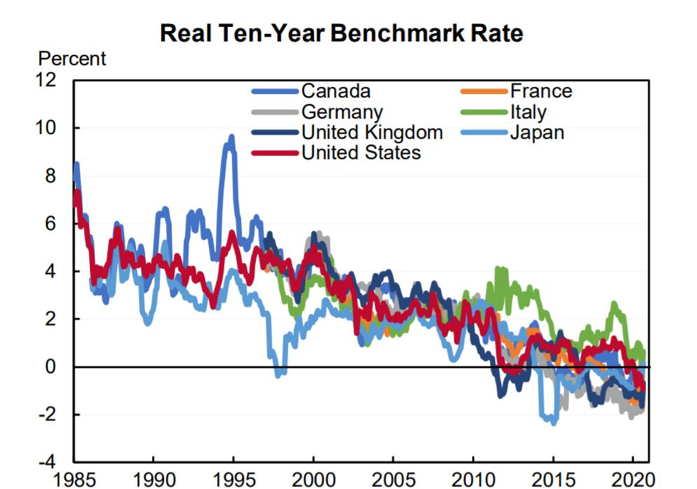

However, it is worth noting that the action of these central banks has been more reactive than proactive, more reflex than cause, and in their absence, macroeconomic performance would have been even more mediocre than it has been. The fact is that real interest rates—short and long term—have been declining for decades (see real 10-year benchmark rates in Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Peterson Institute of International Economics, 8 October 2020.

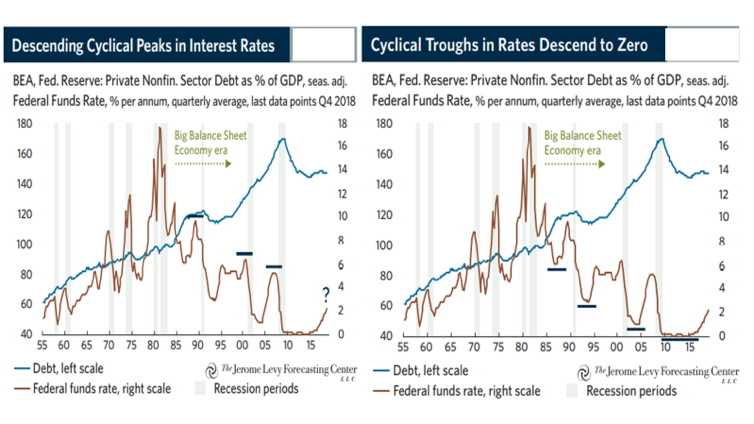

The counter-cyclical role of central banks has led them to take corresponding measures, with descending peaks and troughs over time (see the U.S. case in Figure 2). Since there has been no inflation acceleration, it can be assumed that ‘natural’ interest rates—those in which savings and investment flows are close enough to prevent excess demand or supply from causing inflation or recession—have been falling.

Figure 2: Declining U.S. interest rate peaks and thoughs

Source: Levy, D.A. (2019). Bubble or nothing. The Jerome Levy Forecasting Center LLC, September 2019.

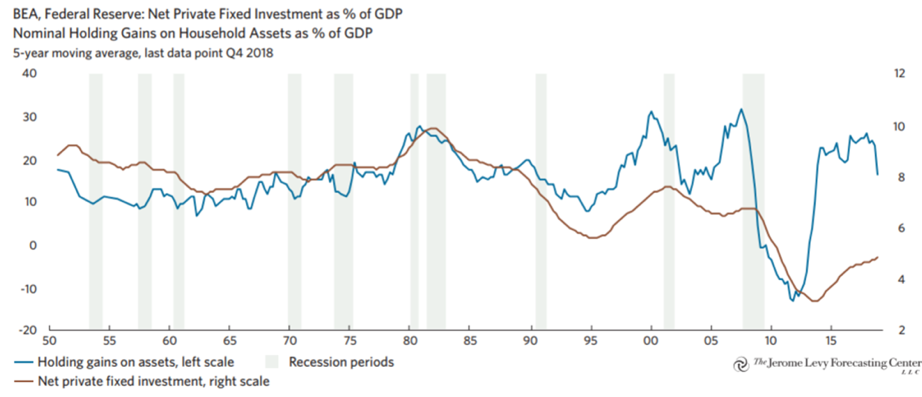

Strictly speaking, there seems to be a mismatch between the trend of increasing stocks of financial wealth, occasionally cut by shocks and crises, and the creation and incorporation of new assets accompanying real economic expansion. This underlies what Levy (2019) called the U.S. “Big Balance Sheet era” depicted in Figure 2. This is also illustrated in Figure 3 in the case of the U.S., where one may notice the mismatch between nominal holding gains on household assets as a share of GDP, and net private fixed investment, also as a share of GDP (with a brief convergence during the global financial crisis). Over time, the excess of savings over investments ends up leading to lower average real interest rates.

Figure 3: U.S. household assets vs. private investments

Source: Levy, D.A. (2019). Bubble or nothing. The Jerome Levy Forecasting Center LLC, September 2019.

COVID-19 is helping reinforce such trends. As in other historical pandemic experiences, those who can, raise their individual savings for precautionary reasons. The uneven nature of the impacts of the pandemic, affecting mainly the bottom of the income pyramid, should increase the savings ratio as a proportion of GDP.

In addition, the preference for safer assets—such as bank deposits and government bonds, which are considered low risk—has increased, pushing down returns on such assets. The public deficits incurred by advanced countries, reflecting their responses to COVID-19, and the consequent increases in public debt are mitigating the mismatch between demand and availability of the assets that are considered safe.

In our previous article, on “real and financial disconnect”, we observed that the “role of superhero fulfilled by the Fed's monetary policy”—and that of other central banks—seems to be exhausted. It is not by chance that banks have demanded the strengthening of expansionary fiscal policies.

During its annual meeting (Oct. 12-18, 2020), the International Monetary Fund called on countries not to act too early in demobilizing their fiscal policies against the impacts of COVID-19. Low interest rates—and with the tendency to continue as such—would allow for the expansion of public debt without going into explosive trajectories. In the Financial Times, there was talk of “death of austerity” (October 16), contrasting the tone of the IMF now with a stronger reference post the 2008-2009 global financial crisis to the need for eventual fiscal correction programs in the medium term.

Before concluding, it is worth remembering that the ‘death of austerity’ can be decreed where and while issuers of public debt do not need to worry about returns demanded by buyers as compensation for risks, as is the case today with the advanced economies, whose sovereign bonds can be absorbed without major difficulties. The transplantation of the idea to contexts where this is not the case can have opposite and catastrophic effects.

The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author.