Publications /

Opinion

Emerging market economies (EM) as a special class of financial assets have recently been subject to two competing tales. On the one hand, there is evidence of continued financial deepening and further integration within the global financial system, while the offer of higher yields remains hard to find elsewhere. On the other hand, there are frequent bouts of fear of systemic unwinding of positions triggered by investors “exiting” EM that exhibit signs of weak or unclear macroeconomic foundations.

The upbeat tale finds support, e.g. in the fact that, taking advantage of the relatively benign environment of low interest rates and available global liquidity, many developing economies heretofore perceived as weak candidates have debuted in the sovereign debt markets attracting large volumes of foreign exchange (Gevorkyan and Kvangraven, 2016). More recently, what seemed at times to be a peak in sovereign borrowing has continuously been topped off as investors keep reaching for the yield and flows keep moving to EM. Last month, e.g. the IIF EM Portfolio Flows Tracker and Flows Alert reported a further strengthening of portfolio flows to emerging markets after the Brexit vote. Some geographical disparity has been showed – inflows to EM Asia and Latin America, modest outflows from EM Europe and Africa/Middle East – but non-resident portfolio flows to EM as a group climbed from $13.3 billion in June to $24.8 in July.

The downbeat story, in turn, has occasionally assumed the lead, combining episodes of overall rising risk aversion and groups of EM deemed to be in correspondingly more vulnerable positions. Like the “taper tantrum” in the summer of 2013 when the early references by the Fed to a future end of quantitative easing led to unwinding of positions on the then “fragile 5” EM (Canuto, 2013a), or when fears of a hard landing in China’s growth transition generated portfolio adjustments in other EM (Canuto, 2014a) (Canuto and Gevorkyan, 2016). While concerns about high levels of EM corporate debt leverage have remained at the forefront, easing of fears about China’s landing has more recently improved the risk-adjusted return prospects of EM as illustrated by flow figures of last month.

Changes in narrative have underlined financial ebb-and-flows

As the authors of this piece have highlighted in a recently released book - Gevorkyan and Canuto (2016) - those ebb-and-flows in EM financing have been accentuated by a change of narrative regarding EM structural strengths in the last few years. Not long ago, some analysts - including one of us (Canuto, 2010) - were anticipating a switchover in the growth engines of the global economy, with autonomous sources of growth in emerging and developing economies compensating for the drag of struggling advanced economies.

To be sure, the baseline scenario for the post-crisis “new normal” then outlined entailed slower global economic growth than during the pre-2008 boom. For major advanced economies, the financial crisis marked the end of a prolonged period of debt-financed domestic consumption, based on wealth effects derived from unsustainable asset-price overvaluation. Later on, attention came to be increasingly given to several hypotheses of “secular stagnation” in those economies (Canuto, 2014b).

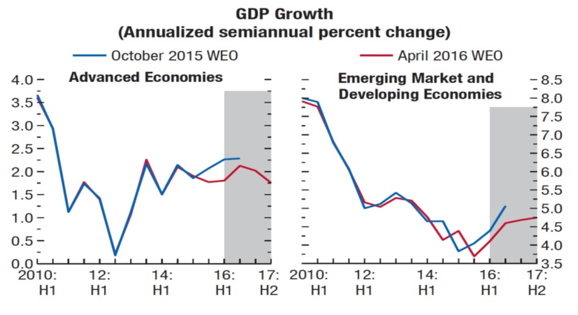

However, 5 years of decreasing growth rates in the emerging market world – see Figure 1 – have thrown some cold shower on the enthusiasm about a switchover of locomotives. Even if there remains a growth differential – with some revival forecast by the IMF for next year – the fact is that the growth downward transition in China’s rebalancing, lower commodity prices, the exhaustion of domestic stimulus policies and the permanence of some structural flaws in most EM have led to a retrenchment of the expectation of a decoupling and even partial rescue of advanced economies by them.

Figure 1 - Growth differential: decreasing but positive

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, April 2016

It has become apparent that emerging-market enthusiasts underestimated at least two critical factors (Canuto, 2011; 2013b). First, emerging economies’ motivation to transform their growth models was weaker than expected. The global economic environment – characterized by massive amounts of liquidity and low interest rates stemming from unconventional monetary policy in advanced economies – led most emerging economies to use their policy space to build up existing drivers of growth, rather than develop new ones.

The second problem with the above mentioned emerging-economy forecasts was their failure to account for the vigor with which vested interests and other political forces would resist reform – a major oversight, given how uneven these countries’ reform efforts had been prior to 2008. The inevitable time lag between reforms and results has not helped matters.

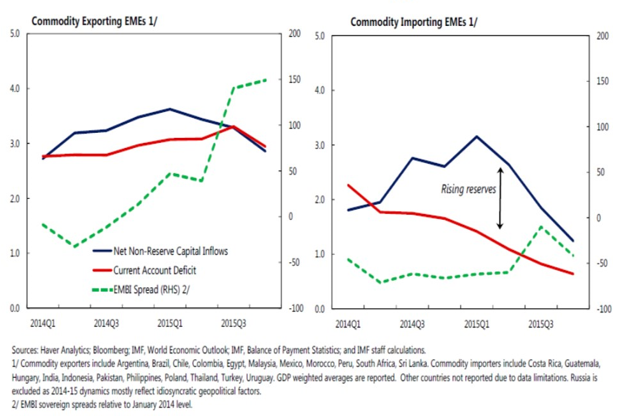

The most recent cycle of global financial flows often looks like to be running out of steam, in the wake of the phasing out of the US accommodative monetary policy stance, while concerns over the advanced economies’ recovery remain. The period of large-scale speculative financial flows and broad access to credit in emerging markets does not seem likely to return, despite ebbs and flows already mentioned. Even with occasional reversals of the downfall in foreign capital flows, emerging markets have already been coping with less benign external finance conditions (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Selected EMs: Capital Inflows, Current Account and Cost of External Financing, 2014-15

Source: IMF, 2016 External Sector Report, July 2016

Differentiation among emerging markets is coming to the fore

As approached in Gevorkyan and Canuto (2016), emerging markets as a class of economies exhibit a lot of heterogeneity in many regards. As highlighted by IIF (2015), notwithstanding a relatively clear dividing line between EMs and advanced economies, EMs are quite heterogeneous across various metrics. Their responses to shocks differ substantially according to their economic structures, such as dependence on external financing and on commodity exports.

Take for example the case of smaller, net importer, economies in transition in Eastern Europe and Former Soviet Union. There the institutional basis and economic structure are yet to evolve in a solid, established, form able to withstand unexpected and severe external pressures (see e.g. Gevorkyan, 2015 and Gevorkyan, 2011).

Taking all of the above together three critical points emerge as core features of medium term developments in the broader group of emerging markets, small countries included.

First, growth rates will remain sub-par across those heavy-weight EM dragged down by recent underperformance (e.g. Brazil, Russia), while China is expected to settle to growth rates much lower than in the period up to 2011 and India still needs structural reforms as a precondition to lift its growth pace to its potential.

Second, EM will continue to capitalize on global low interest environment and abundant liquidity even as they implement structural adjustment policies and reforms, as well as while part of their non-financial corporates deal with the legacy of the excess debt leverage built until recently.

Third, as a result, a propensity to undergo periodic episodes of instability and volatility in global financial markets will persist. Get ready for a continuous dispute between the two financial tales about EM, as well as to increasing efforts of differentiation among their assets.

This article has been originally published on the Huffington Post