Publications /

Policy Brief

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the sixteenth largest bank in the United States, experienced a bank run in early March 2023, and was closed by the U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC) on March 10. This bank failure, followed by others, creates fear of contagion throughout the U.S. and global banking systems. This Brief identifies four factors leading to the SVB crisis: i) Sharp interest rate increases by the Federal Reserve, which adversely affected SVB’s income and balance sheet; ii) The failure of SVB’s management to manage maturity mismatches; iii) The failure of the regulatory and supervisory agencies in discovering the problems and fixing them; and iv) The failure of the 2018 revised Dodd-Frank regulations to subject mid-size banks such as SVB to the same rigorous requirements that large banks have to meet, such as stress tests. The Brief also discusses lessons from the crisis.

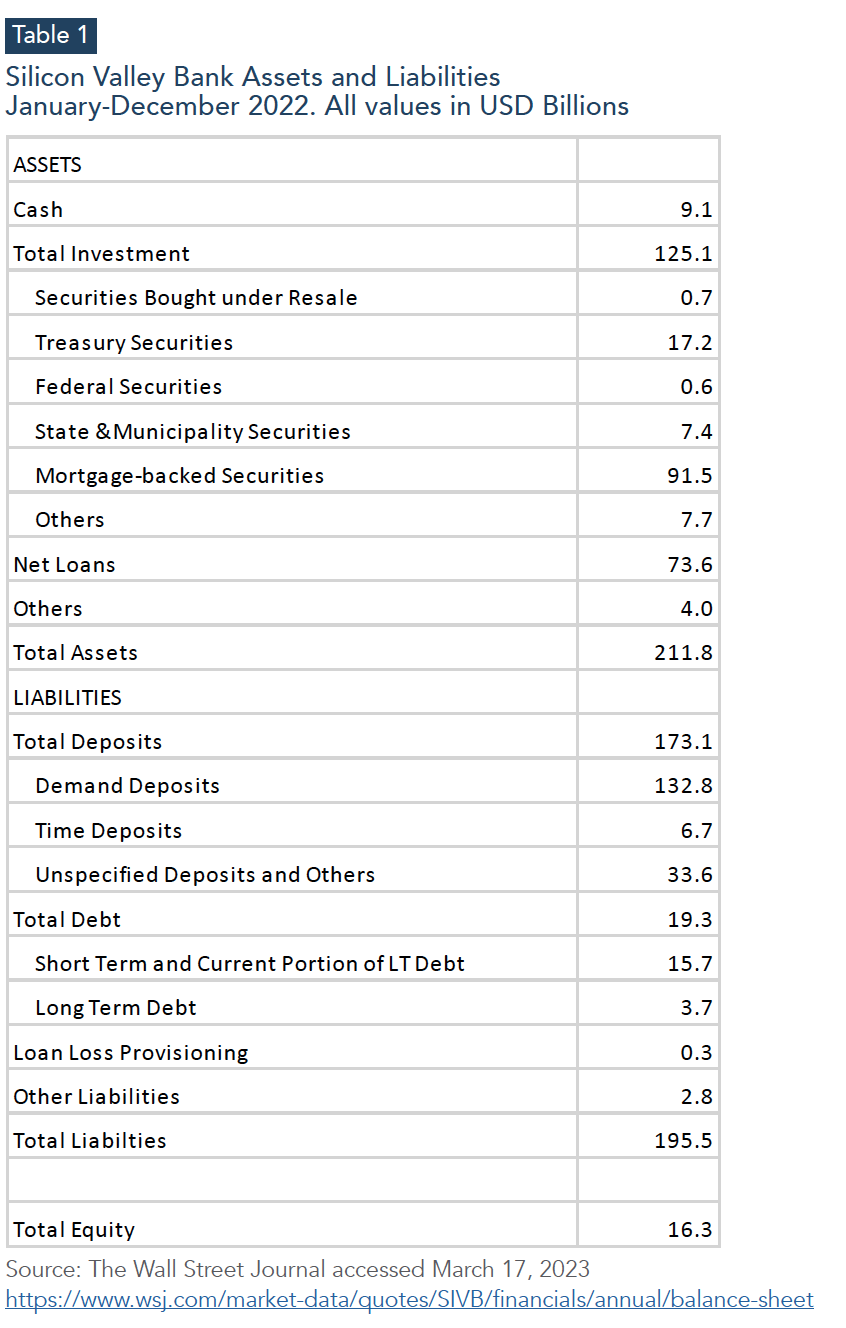

On March 10, 2023, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) seized the assets of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the sixteenth largest bank in the U.S., after it experienced a run. This marked the second largest bank failure in U.S. history after Washington Mutual in 2008. A few days later, Signature Bank of New York also failed. A third major U.S. bank, Third Republic Bank of San Francisco, is at time of writing experiencing liquidity problems. The impact of these bank failures on the U.S. and global financial systems is significant and far-reaching. This Policy Brief reviews what happened to SVB to see if there are any lessons to learn. Table 1 shows the assets and liabilities of SVB as of December 2022, prior to the crisis.

The run on SVB appears to have been a classic bank run, which is well documented in the literature, and for the modeling of which Douglas Diamond, Philip Dybvig, and Ben Bernanke won the 2022 Nobel Prize for economics.

What happened? First, since March 2022, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates in the U.S. by 4.5 percentage points. The yield on one-year U.S. government Treasury notes was 5.25% in March 2023, up from less than 0.5% at the beginning of 2022, while yields on 30-year Treasuries climbed by almost 2 percentage points. This caused the market value of previously issued debt—like government Treasury Bills and Bonds—to plunge, especially for longer-dated debt. For example, it is estimated that a 2-percentage point rise in a 30- year bond’s yield can cause its market value to drop by around 32%. SVB had a massive share of its assets—$117 billion or 55%—invested in fixed-income securities, such as U.S. government bonds and mortgage-backed securities (Table 1). In this regard, SVB was not alone: in the last decade, with near-zero interest rates, banks and financial institutions have held large volumes of Treasury bonds. Normally, if interest rates had not risen, a bank could hold onto these T Bills or Bonds or securities until maturity, so that it could collect their original face value, and would then remain both solvent and liquid. But when interest rates rose by so much and so quickly within such a short time, the bank faced a mismatch of its income and expenditure.

A close look at SVB’s balance sheet illustrates this point. At the end of 2022, SVB’s $117 billion investment assets consisted of Treasury Bills and Bonds and Government agency mortgage-backed securities (Table 1). These securities could be classified into two types: ‘Available for Sale’ (AFS) and ‘Held to Maturity’ (HTM). The former (about $26 billion) are securities the bank is free to sell at any time, marked at market value (and hence implying realized losses in the current high interest rate environment when the transaction is carried out). The latter (about $91 billion) consists of fixed-income securities to be kept until maturity—hence valued at par. Every quarter, SVB could shift securities between AFS and HTM. In the current environment of high interest rates, this transfer between AFT and HTM would carry a hit on equity.

According to Nobel laureate Douglas Diamond1, the bonds in AFS generated only about a 1.8% yield with an average maturity of 3.6 years as of mid-March 2023, while the return on HTM bonds was about 1.6% with 10-year maturities. SVB’s net loan portfolio of $74 billion (Table 1) generated a return of under 4% after loan loss provisioning. At these rates, SVB could afford to pay 0% interest on checking accounts and 1% interest on money market funds, and if interest rates had not changed, it would still be solvent and liquid. But when interest rates rose, the bank had to compete with other sources, and SVB was forced to pay 4.5% on its savings deposits. Meanwhile it was getting less than 2% in income from its assets. This clearly could not last for long.

One particular feature of SVB was the dominant share of demand deposits in total (over two-thirds), indicating the need for the bank to be ready for large withdrawals at short notice. This need was clearly not matched by the long term fixed-income securities held by the bank. With surging interest rates, SVB depositors, who are mostly Silicon Valley high- tech startups and/or in venture capital—the business of which has been in decline since last year—began to withdraw their money to search for higher returns elsewhere. When SVB could not meet this demand from its cash reserves (4.3% of assets compared the industry’s average of 13%), the bank decided to sell $21 billion of its securities portfolio at a loss of $1.8 billion. It then tried to raise over $2 billion in new capital. The call to raise equity led its customers to lose confidence in the bank and rush to withdraw cash. Because about 90% of deposits at SVB exceeded the $250,000 insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., these customers knew their money might not be safe were the bank to fail. Of course, if and when all customers of a bank want to withdraw money, even the best bank in the world will have a bank run: a self-fulfilling prophecy, which is exactly what happened at SVB. In a single day, $42 billion in deposits was withdrawn.

Why can’t a bank pay all its depositors if they ask for their money all at once? By definition, a bank is a company that borrows short and lends long. This is how banks can play their (critical) financial intermediation role in an economy, by channeling funds between savers and investors. Demand deposits, for example, represent money that a bank borrows from depositors and must repay whenever depositors want. Banks pay very little interest on these demand deposits or other short-term liabilities, but invest in long-term assets (T Bills or Bonds, mortgages, or corporate loans, for example). These assets earn a high return, but can’t be quickly liquidated (or at least, in the case of T Bills or Bonds, not at face value in current market conditions). The difference between the high return on banks’ long-term assets and the low cost of their short-term liabilities is the interest rate spread, and that is how banks make profits. But this is a risky business that relies entirely on the trust factor. So, if all the people who deposited money into the bank no longer trust the bank and want their money back all at once, the bank simply won’t be able to pay them all.

Lessons from the crisis. Viewed this way, bank runs such as those experienced by SVB and Signature Bank are bound to happen. Who is then responsible for this bank run? The first culprit is the Federal Reserve. The pace of its interest rate increases was too fast and abrupt, and did not leave enough time for banks to adjust the duration of their portfolios. Second was the SVB management itself, for making the mistakes mentioned above. The maturity mismatch between its demand deposits and its securities was impossible to ignore. Third is the regulatory agency responsible for supervising and regulating SVB, in this case, the bank supervisor in the San Francisco District of the Federal Reserve. Finally, except for the largest banks, most U.S. banks, including SVB, are not required to follow the Dodd-Frank Act’s rigorous rules (such as application of prudential standards, stress test requirements, and mandatory risk committees), because their assets are below the $250 billion threshold (which used to be $50 billion until 2018, when the regulations were revised). In this situation, many banks will have weak risk-management structures.

Under current policy, banks with over $100 billion in assets are directly supervised by the Fed, with Fed staff and governors in Washington D.C. setting the direction for oversight only, and the actual day-to-day monitoring managed by supervisors from various Fed regional banks. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco was responsible for Silicon Valley Bank’s supervision. This agency bears some responsibility for allowing SVB to grow so fast and end up with 90% uninsured deposits, which made it susceptible to a run.

One of the lessons to learn from the SVB crisis is that the central bank should take the time to warn the banking system in advance of its monetary policy. The pace of the central bank’s interest rate increases has a critical impact on the solvency and liquidity of the banking sector. Another lesson is that the regulatory and supervisory role of the central bank needs to be reviewed thoroughly and frequently. Finally, in terms of bank risk management, diversification of assets and liabilities, and paying close attention to their maturity structures, would go a long way toward securing customers’ trust and preventing bank runs. According to Douglas Diamond, a good bank should create safe assets out of risky ones by diversifying. Because not all depositors need their money at the same time,

that diversification allows the bank to economize on what it holds in cash and liquid assets. This diversification principle also applies to the liability side of the balance sheet, and a good bank should have a wide, varied range of depositors.

What the authorities have to worry about now is the contagion effects. While the largest U.S. banks remain sound, some regional banks may not fare so well. The Fed’s recent policy of a blanket guarantee for all depositors (over and above the $250,000 ceiling provided by FDIC) is not wise because it creates moral hazard that could lead banks to make risky investments.