Publications /

Opinion

An Executive Order issued on July 30 by President Donald Trump hiked United States tariffs on imports from Brazil by 40%, in addition to the 10% established on April 2—the so-called ‘Liberation Day’ when Trump set out ‘reciprocal tariffs’ on countries around the world.

The decree came with a long list of exemptions for Brazilian exports. For a number of product lines, the 10% April 2 tariff will continue to apply. These include air transport equipment, orange juice, furniture, fuel, and iron ore. For other items—coffee, meat, fruit, etc.—the 50% tariff will start to apply from August 6. Somewhat less than 40% of Brazilian exports remained exempt from the 40% additional tariff.

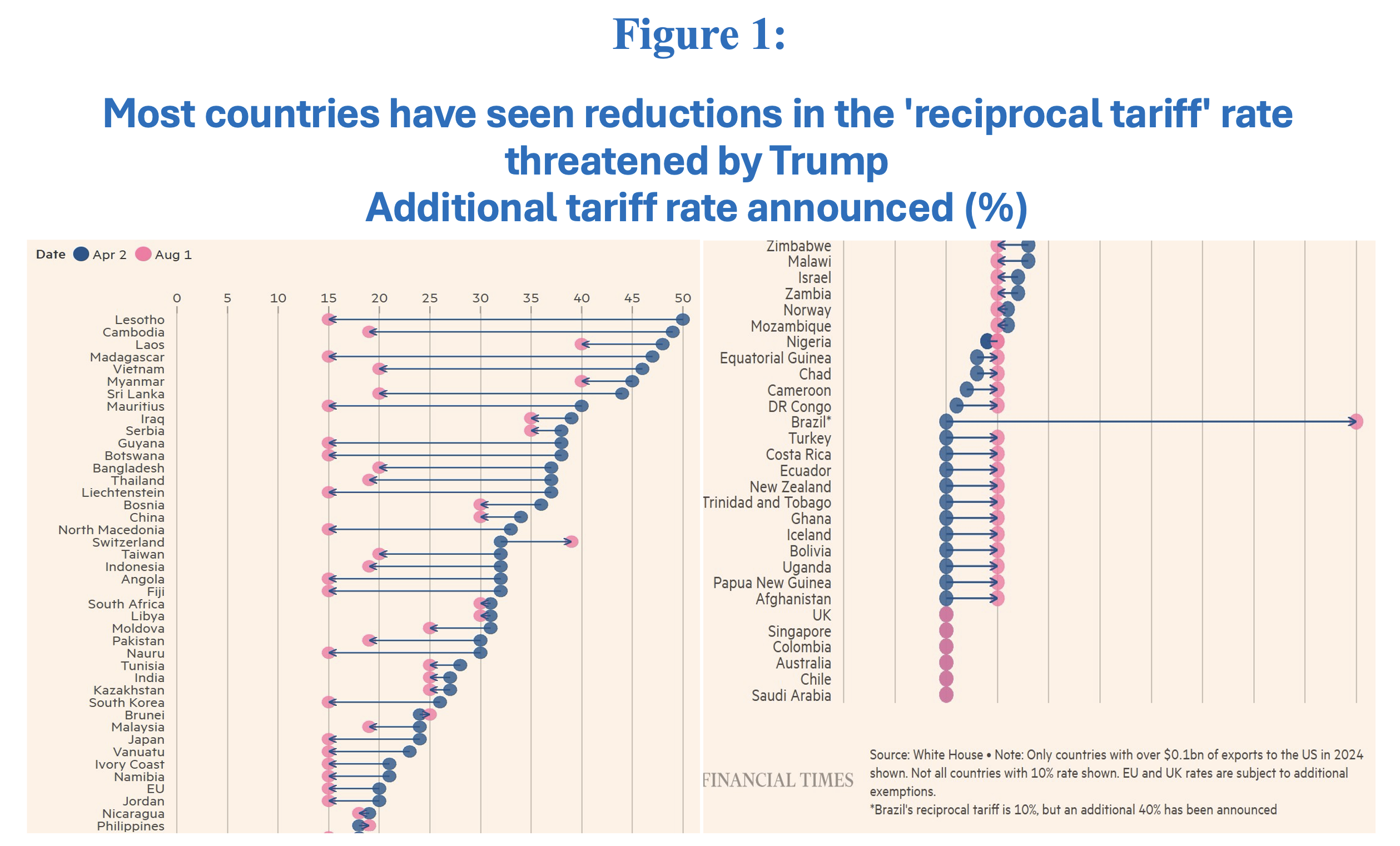

Still, the effective average tariff, calculated by J.P. Morgan based on the weights of the sectors in last year’s Brazilian export bill to the U.S., will reach 32.7%—slightly below the 37.8% expected with Trump’s letter to Lula on July 9, when the former communicated that tariffs would move up to 50%. In any case, the effective average tariff will be well above the 11.7% established on April 2, and 1.3% before the “reciprocal tariffs”. In any case, the level of tariffs on Brazil is unique case among the countries affected by Trump's tariff war (Figure 1).

What is the expected impact on the Brazilian GDP? A rule of thumb often used in recent calculations is that Brazilian GDP tends to shrink by 0.2% to 0.3% for every 10-percentage point increase in U.S. tariffs on the country. Therefore, the increase compared to the Liberation Day tariffs could have a potential negative impact of between 0.4% and 0.6% of GDP. This estimate should be seen as a ceiling, since diversification to other trading partners—especially considering that commodities constitute almost half of Brazilian exports to the U.S.—can mitigate the ultimate effect of U.S. tariffs. On the other hand, this negative shock to demand for Brazilian products clearly reinforces the likely economic slowdown currently underway in the country.

The expected GDP growth rate shown in the Central Bank of Brazil’s weekly FOCUS projections report—currently 2.23%—should be discounted by something close to 0.15 percentage points, likely in the second half of the year. So, nothing dramatic. Of course, the damage is likely to be greater if it is also projected for all of 2026, when it would reach about 0.3%.

There are, however, some uncertainties. Trump’s Executive Order indicates that if Brazil retaliates, the U.S. administration may increase the ad-valorem tax rate. At the same time, the suggestion by U.S. Secretary of Commerce, Howard Lutnick, that tariffs for natural resources that are not grown in the United States, including coffee and cocoa, could be exempt from import tariffs when trade deals with producing countries are reached.

Will there be any effect on Brazilian inflation? If some foods that receive the 50% tariff—such as coffee and meat—don’t find alternative markets abroad, their domestic prices will tend to fall. It should be borne in mind, however, that they may reach the U.S. market indirectly, or even continue to be absorbed at higher prices. In any case, it’s safe to say that the effect on Brazil’s inflation index (IPCA) is likely to be small and temporary.

How can the peculiarity of Trump’s treatment of Brazil in his tariff war be understood? More generally, Trump has been claiming victory because other economies haven’t retaliated against his tariffs. China is a unique case, because it has been able to use its global dominance in the processing of critical mineral resources and rare earths as an effective threat.

Trump has long portrayed the United States as a victim of unfair trade. His tariffs target trade in goods, where the country has long run huge and growing deficits, while achieving positive balances in services transactions. Remember that, when announcing his Liberation Day tariffs, he declared that America had been “raped, pillaged, and plundered” by foreign “scavengers”.

Trump’s electoral victories in 2016 and 2024 were aided by his successful marketing of a return-to-the-past project, reviving the manufacturing industries of past decades: Make America Great Again. While the hardships of the country’s middle class also had to do with technological change without adequate educational adaptation for workers in lost industrial sectors, it was easier to point the finger at globalization and trade deficits—and China in particular.

This return-to-the-past project is unrealistic, especially because technology has changed. Furthermore, tariffs will have a particularly negative impact on the cost of living for the lower income brackets in the U.S. At the same time, as Richard Baldwin has pointed out, only one in ten middle-class workers in the U.S. have jobs in economic sectors protected by tariffs. But that doesn't matter: these negative effects will take some time to be felt, and in the meantime, President Trump can declare victory via tariffs.

But Trump's tariffs also have a ‘transactional’ dimension, to use the characterization of his Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, meaning that the intention is to coerce the other side into concessions in areas other than trade. Judging by the letter to President Lula sent by President Trump on July 9, the ongoing legal process in Brazil where former President Bolsonaro has been indicted for an attempted coup d’état, and the Brazilian Supreme Court’s actions on Elon Musk’s firm for non-compliance with Brazilian law, are ‘reasons’ for the punitive nature of the higher tariffs.. Notice that no reference was made to BRICS countries or to a US-dollar replacement in foreign transactions among its members, while Trump had previously referred to these as motivations for special tariffs.

The costs of Brazilian tariff retaliation would likely be high for its economy, because of risks of even higher U.S. tariffs and because of Brazil’s domestic use of current imports from the U.S. At the same time, it is unimaginable that Brazil will fall into the trap of accepting a ‘political’ negotiation plan. Brazil will have to count on some eventual support from U.S. domestic opponents of the tariffs, in addition to any other trade matters that may come up in bilateral conversations between Lula and Trump that may take place in the near future. Beyond that, Brazil will just have to bite the bullet.