Publications /

Opinion

All economies affected by the pandemic have something in common. The rate of vaccination of the population—quite different in different countries—has been the main factor determining the prospects for the resumption of economic activity, as it is a race against local waves of transmission of the virus.

Personal contact-intensive services have borne the economic brunt of the pandemic. To the extent that vaccination enables them to restart, one may even be able to witness some temporary dynamism in the sector because of pent-up demand. However, international tourism will not be included at the outset, since vaccination will have to reach an advanced level both at the origin and destination of travelers.

But let us not be deceived: the pandemic will leave scars and countries will not return to where they were. There will be a need for retraining and job reallocation for part of the populations of all countries.

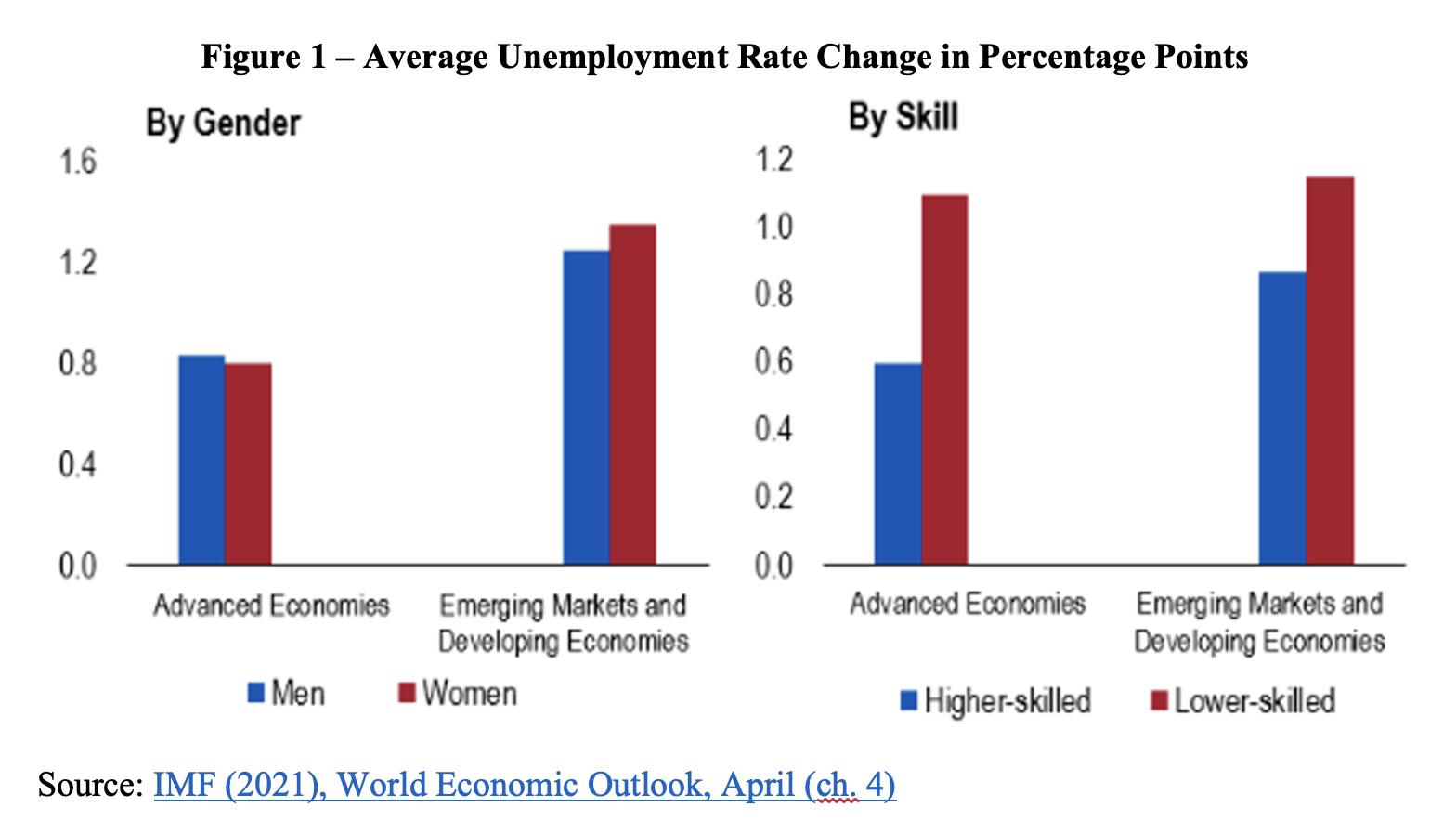

The pandemic is leaving a trail of unemployment, particularly affecting minorities, low-skilled workers and, in Emerging Market and Developing Economies, women, who predominantly occupy jobs in contact-intensive services. Figure 1 displays estimates presented in chapter 4 of the IMF April World Economic Outlook released on March 31.

Before the pandemic, it was already known that ongoing technological changes—automation and digitalization—were posing challenges in terms of the need for training or retraining for part of the workforce. Well then! The response of companies and consumers to the pandemic has deepened these trends and is not expected to be entirely reversed.

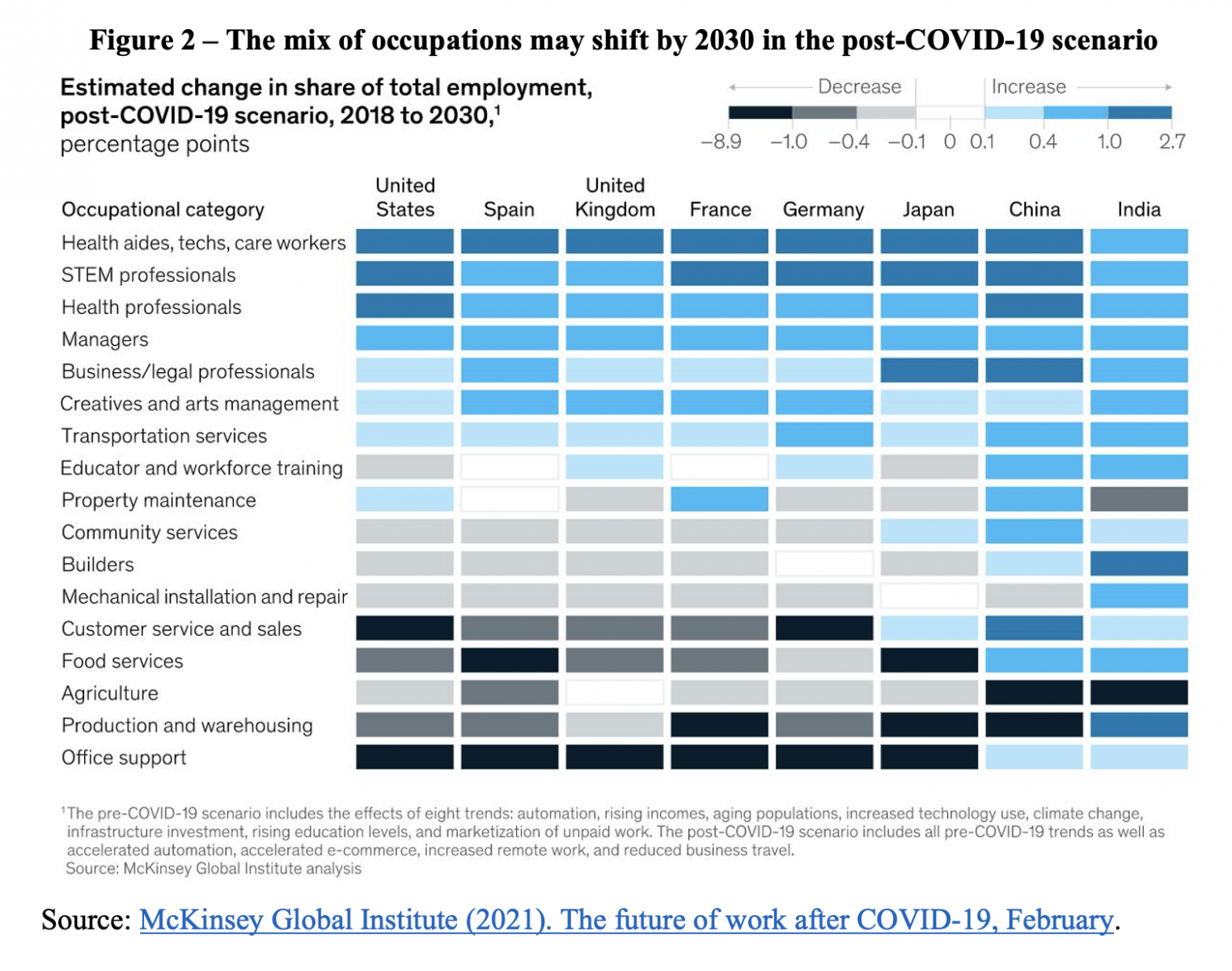

A February 2021 report by the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that in eight countries (China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States), more than 100 million workers will have to find new, more qualified jobs by 2030. This is 25% more than they had previously projected for developed countries. Figure 2 shows their estimates of shifts in occupations by 2030, with a relative rise in healthcare and science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), while jobs in food service and customer sales and service roles decline. Less-skilled office support roles would also tend to shrink.

Why? Many of the practices adopted during the pandemic are likely to persist. Where done, consumer surveys indicate that sales via e-commerce, which have grown substantially during the crisis, are not expected to shrink too much. Also, remote work will not be fully reversed, with the hybrid organization of work processes becoming more common. The fact that employees in remote occupations have worked more hours and with greater productivity during the pandemic will encourage continued telework.

McKinsey suggests that changes in “work geography” will have consequences for urban centers and workers employed in services, including restaurants, hotels, shops, and building services—25% of jobs in the United States before the pandemic, according to David Autor and Elisabeth Reynolds (The Nature of Work after the COVID Crisis: Too Few Low-Wage Jobs; July 2020). Indeed, demand for local services in cities has dropped dramatically as remote work has increased, regardless of confinement.

Autor and Reynolds indicated four trends for the world of work after the pandemic. In addition to automation, they highlighted the increase in remote work, the reduction of density of workplaces in urban centers, and business consolidation. The latter is due to the growing dominance of large firms in many sectors, something exacerbated by the bankruptcies of smaller and more vulnerable companies.

All these trends have negative impacts on low-income earners and the distribution of income. They tend to increase the efficiency of processes in the long run, however, leading to harsh consequences in the short and medium terms for workers in personal services, who are generally not present among the highest paid. Workers at the top of the wage pyramid, including professionals in STEM, will see their opportunities grow.

Technological progress is one of the main causes of the increase in income inequality in advanced countries since the 1990s. The acceleration of inequality with the pandemic therefore tends to intensify the challenges. In a way, it can be said that the pandemic is accelerating history, rather than changing it.

The role of public policies will be central in the post-COVID-19 world, both in strengthening social protection—including through unemployment insurance and income transfer programs—and in the requalification of workers. Instead of denying technological advancement, it is better that public authorities help people to adapt, minimizing the resulting scarring.

The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author.