Publications /

Opinion

The global reach of COVID-19 is now clear. In a short time, country after country has suffered outbreaks of the new coronavirus, with each facing a three-fold shock: epidemiologic, economic, and financial. In addition to dealing with their own local coronavirus outbreaks, emerging market and developing countries have faced additional shocks from abroad.

Flattening pandemic curves saves lives

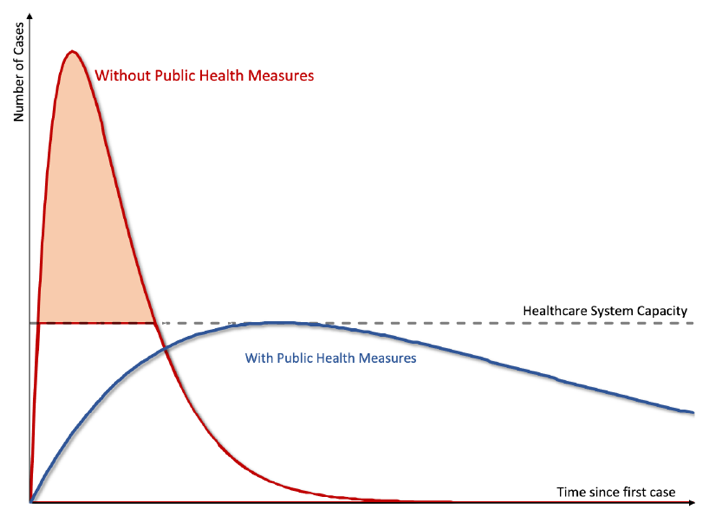

The coronavirus crisis is primarily a public health issue, demanding containment policies that inevitably lead to shocks to economic activity. A major reason for containment is the widespread perception that, given the dynamics of infection—and corresponding numbers of people in need of clinical care—local clinical care capacities risk being swamped, with higher death tolls, in a ‘do-nothing’ scenario. Therefore, policies to flatten the pandemic curve and gain time become vital, regardless of whether or not they reduce the absolute number of infected cases. Figure 1 from Gourrinchas (2020) illustrates the point. Even assuming that the overall number of infections would be the same, with or without public health containment policies, lives are saved if the curve is flattened.

Figure 1: Flattening the Pandemic Curve

Source: Gourrinchas (2020).

Two major types of policy to contain or simply slow the spread of coronavirus have been applied. The first is to identify and quarantine infected people. This approach has been pursued in Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea. There are two prerequisites for such an approach to be successfully implemented: there must be government capability to use technology and information to track and monitor individuals, and the ability to apply widespread coronavirus tests to the population. That is not the case in most countries.

The second type of containment policy is to adopt social distancing, with various degrees of government enforcement, including minimizing person-to-person contact by banning travel, temporary closure of workplaces and schools, and official recommendations or orders for people to stay at home. Such horizontal approaches include some demarcation of essential activities, which are excluded from physical mobility restrictions. Social distancing can be used in combination with the selective focus wherever there is capacity to do the latter.

The pandemic curve generates a recession curve that also needs to be flattened

The coronavirus pandemic has led to both negative demand and supply shocks to the economy. While demand and supply would in any case be negatively impacted in a do-nothing scenario, the impact tends to be exacerbated by social distancing policies.

As Hinh Dinh (2020) aptly remarked: “a COVID-19 crisis is likely to be more disruptive, yet of a shorter duration than a recession.” Notwithstanding its shorter duration, its disruptive nature may leave ‘scars’, impeding a return to the point the economy was at prior to the shock. Solvent but suddenly illiquid firms may go bankrupt, unemployment rises rapidly, demand and revenues for small businesses rapidly vanish…

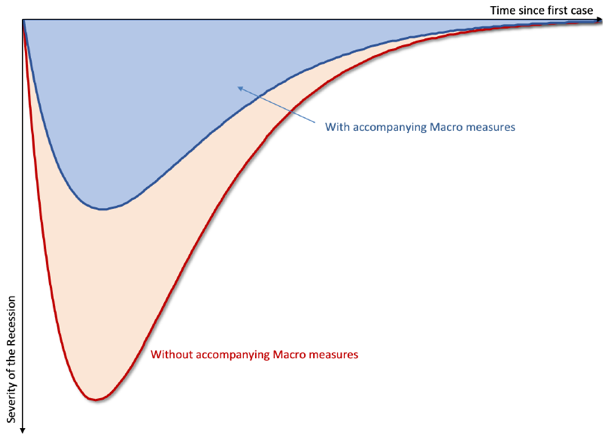

That’s where an extraordinary role of the state as a catastrophe insurer comes to the fore, providing fiscal support—additional resources for healthcare systems, income transfers to crisis-affected people, tax relief—and credit available at favorable conditions to vulnerable firms. These emergency and temporary measures, with rising public debt as the form of finance, are geared to minimize the disruptive consequences of the temporary but deep sudden stop of the economy. Figure 2 illustrates such a flattening of the recession curve, happening in tandem with the flattening of the pandemic curve.

Figure 2: Flattening the Recession Curve

Source: Gourrinchas (2020).

Is there a trade-off between saving lives through containment policies and the output losses that are their consequence? Using the historical experience of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, Correia et al (2020) found that cities where non-pharmaceutical interventions took place earlier and more aggressively did not perform economically worse and, if anything, grew faster after the pandemic was over. Their findings suggest that “non-pharmaceutical interventions not only lower mortality, but also mitigate the adverse economic consequences of a pandemic” (Correia et al, 2020). The economic havoc wreaked by the pandemic dynamics in a ‘“do-nothing”’ scenario cannot be assumed as economicallyto be stronger greater than the onein a scenario with containment policies.

Developing countries face additional shocks from abroad

Dinh (2020) gives several reasons why flattening both the coronavirus infection and the recession curves in non-advanced economies is likely to be harder. Developing economies have faced simultaneous shocks from their external environment, as pandemic and recession curves unfold abroad. In addition to supply shocks derived from unavailable imports that are key to local value chains, in poorer countries, commodity prices, tourism, and remittances have collapsed (Canuto, 2020). Furthermore, the third part of the coronavirus crisis—shocks to finance—have also hit developing countries.

The pandemic and economic aspects of the coronavirus dynamics triggered shocks to financial markets in advanced countries. The prospects of deteriorated earnings and heightened uncertainty have led to a broad portfolio switch from risky assets to the safe haven of U.S. short-term Treasuries. Given the high levels of financial leverage from previous years—including non-banking financial institutions that have become major market makers—successive margin calls have sparked massive asset fire-sales and exacerbated their price falls.

The Federal Reserve has opened an extensive toolbox, establishing new or reinforcing existing channels to make sure that liquidity is conveyed to all corners of the financial system. Rather than lifting again asset prices, the aim seems to be to avoid bankruptcies and short-circuit all the negative feedback loops and channels of contagion that otherwise would hit the real economy.

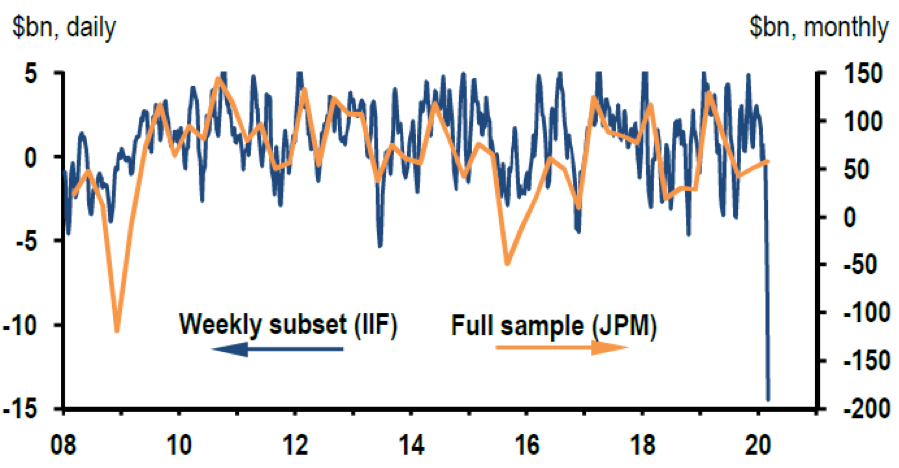

The search for safety sparked by uncertainty and fear has led to a strong wave of capital outflows from emerging markets (Figure 3) and depreciation of their currencies. According to the Institute of International Finance, foreign investors have taken US$83 billion out of emerging markets since the beginning of the crisis, the largest capital outflow ever recorded. Concerns about debt repayment capacity and the dollar liquidity needs of some emerging markets have increased, raising the odds that the coronavirus sudden stop in advanced economies might cause a sudden stop in capital flows to emerging economies.

Poorer developing countries have built up high and unsustainable amounts of foreign debt in the recent past (Kose et al, 2019). Servicing that debt at a time of drought in sources of refinance has become harder as commodity prices and tourism have slumped. All this is happening at the same time as those countries need to face the task of flattening their domestic pandemic and recession curves. The International Monetary Fund and World Bank have called on governments to offer debt relief to help developing countries deal with the coronavirus outbreak.

Figure 3: Emerging Markets: Non-resident Portfolio Flows and Net Capital Flows

Source: IIF and J.P.Morgan estimates

Given current constraints on liquidity and long-term financial provision posed by the balance sheets of multilateral institutions, some ideas about the use of the IMF and the World Bank as vehicles for extending the reach of central bank policies in advanced economies to developing countries have been floated by Hausmann (2020). For instance, US Federal Reserve swap lines recently signed with central banks of other countries could be extended beyond the group that has been recently included (Australia, Brazil, Denmark, Korea, Mexico, Norway, New Zealand, Singapore, and Sweden), either directly or with IMF intermediation. Another mechanism could be the inclusion in the quantitative easing being done by advanced economies’ central banks of the acquisition of less-risky emerging-market bonds, which would create space for international financial institutions to focus on poorer countries.

We need poor and middle-income countries to successfully defeat coronavirus, otherwise it will bounce back to strike all of us.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, and principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil.