Publications /

Opinion

On January 28, both Argentina’s government and the International Monetary Fund staff made announcements about an understanding on new support program. Meanwhile, in addition to the payment of an amortization due on January 28, another payment is also expected in the first week of February. Both payments relate to the previous package, approved in 2018 and substantially disbursed thereafter. Non-payment could sour relations at a critical moment for a new program to be approved by the IMF's board of executive directors in time for disbursements to cover larger obligations due in March.

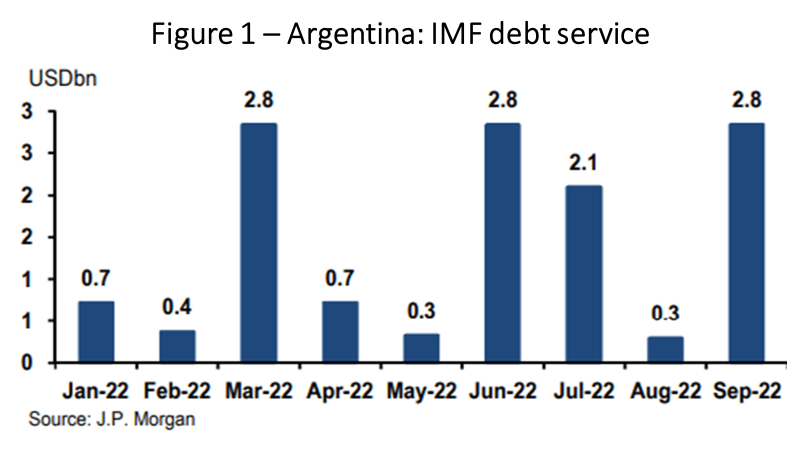

The current squeeze on Argentine foreign reserves is tight. If a new agreement is not approved, Argentina will hardly be able to meet forthcoming payments to the IMF, as the amounts owed will increase sharply from March (Figure 1). A default with the IMF would also have consequences in the near future for Argentina’s other external financing needs, since falling into arrears with the IMF would imply a halt in disbursements from other multilaterals, as well as interruption of trade credit lines.

It would also be bad news for the IMF, given that the package passed in 2018 was the biggest in its history. As Argentina and the IMF need each other to avoid catastrophic results, it would not be surprising if they end up finding a compromise.

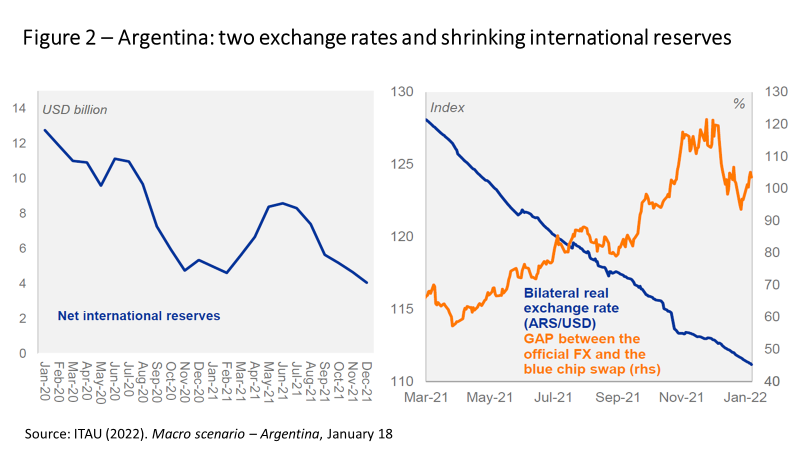

Management of official and parallel exchange rates in Argentina has been draining the country’s reserves, despite trade surpluses, and the allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) in the middle of last year. Central bank interventions in the exchange rate market have led to a depletion of reserves (Figure 2, left panel).

An important issue will be the type and size of a new IMF program. Will the package under negotiation bring new features, or will it simply allow commitments to rollover the IMF debt service, kicking the can down the road?

There is a difference in context between now and 2018, when the previous package was approved. Then, the justification was boosting confidence and the entry of private investors. In practice, the resources ended up being used to pay for capital outflows. Now it is time to reimburse the IMF.

The type of program to be approved matters, in terms of content, size, and deadlines. The IMF has the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) to be used when a country faces heavy medium-term balance-of-payments problems because of structural deficiencies that require time to resolve. Compared to Stand-by Arrangements (SBA), the EFF typically involves a longer program—to help countries implement medium-term structural reforms—and a correspondingly longer payback period.

In principle, if the program is to be an EFF or an SBA depends on the content of the agreed policies. An EFF requires more structural adjustment in exchange for longer repayment deadlines. The 2018 agreement was an SBA, while in a January 28 press conference, Argentine Finance Minister Martin Guzmán referred to an EFF.

The IMF’s next program is expected to include commitments to tackle the current disconnect between official exchange rates and inflation. The Argentine peso increased in value by 12% in real terms against the dollar last year, while the gap between official rates and the blue-chip swap rates has risen (Figure 2, right panel). A fiscal adjustment to reduce deficit monetization—4.8% of GDP last year—will also have to be contemplated.

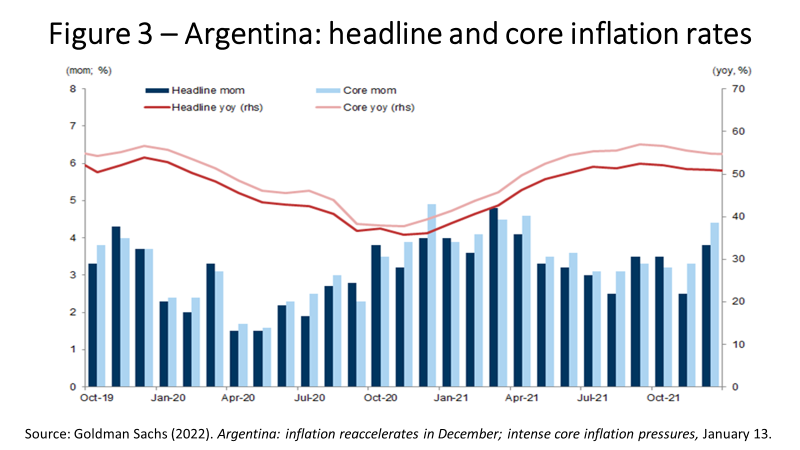

Progress will not be easy on either front, as tackling high inflation (Figure 3) will mean resisting the monetization of public deficits, in addition to no longer resorting to the shortcut of letting the official real exchange rate appreciate as a way of trying to contain inflation.

In January 28 press conference, the Argentine minister provided some details of what, in his words, has already been agreed. Under the new program, the primary fiscal deficit would be gradually reduced from 2.5% of GDP in 2022 to 1.9% of GDP in 2023 and 0.9% of GDP in 2024. Under the program, Argentina would commit to gradually reduce the central bank’s monetization of fiscal deficits: from 1% of GDP in 2022 to 0.6% in 2023, reaching something close to zero in 2024. But “price control agreements” with sellers/retailers would continue as part of the inflation control strategy.

Minister Guzmán stated that the new EFF program would be worth $44.5 billion and would last two and a half years, while authorities would intend to increase reserves by $5 billion in 2022. Thus, the package would cover both the volume of future amortizations with the IMF, as well as what has been paid since September.

Authorities would expect to close the deal by March, before the large principal payment is due. It should be noted, however, that the IMF staff communiqué says that “IMF staff and Argentine authorities reached an understanding on key policies as part of their ongoing discussions on an IMF-supported program.” Anyone who knows the language knows that this means that there are still details to be finalized...

From the point of view of evaluating the package, the details will be important: in the policy conditionality matrix that will underpin the program and the path of fiscal consolidation. Just as challenging as providing a credible commitment to reasonable fiscal consolidation, will be addressing large monetary-financial imbalances (e.g., a very misaligned exchange rate, high inflation above 50% a year, and financial repression mechanisms that are not only widespread, but increasingly more distorted). Everything indicates that the monetary/financial strategy will not be particularly tough.

It will be critical to look at the trajectory of disbursements under the new program in relation to Argentina's scheduled debt service payments to the IMF. A disbursement path ahead of the debt service schedule would give Argentina new net financing in the short term, but the IMF would risk seeing its already very high exposure to Argentina increase further if the program goes off the rails.

Argentina's gross external financing needs over the next three years are expected to be higher than the amortizations of the previous IMF package, while other sources will remain scarce. The current account is currently in surplus, relieving funding pressure. However, maintaining strict restrictions on imports indefinitely does not seem feasible. It is likely that even moderate current account deficits of 1.5%-2% of GDP in 2023 will create financing gaps if, as is likely, resources under the new program are used especially for the rollover of the current debt with the IMF itself, without large additional new liquid amounts.

For now, at least Argentina’s default with the IMF has been avoided. But the course ahead will be difficult, as IMF disbursements will depend on targets being reached.