Publications /

Opinion

The world woke on Monday August 23 to higher international reserves for all countries. A new allocation of US$650 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to its member countries had entered into force (SDR450 billion).

SDRs are an international reserve asset created by the IMF and added to countries' other foreign reserves. It is not a currency that can be used by private agents. Governments, on the other hand, can unconditionality exchange SDRs for currency from other countries and can thus make payments with the latter. It is, therefore, a supplement to countries' foreign reserves, without depending on the issuance of external or domestic debt for its acquisition.

SDR allocations don’t happen often. SDRs were created in 1969 and their general allocations are made to IMF member countries according to their quotas in the Fund. The IMF has the right to ask for SDR cancellation, but that has never happened. Previous general allocations happened in 1970-72, 1979-81 and 2009, accompanied by a special allocation in the latter case. The extraordinary character of the allocation this time is seen in the fact that its amount corresponds to more than double the sum of all allocations made to date.

The exceptional circumstances of the pandemic crisis, putting the external accounts of many economies in a precarious situation, were the motivation. But as allocations follow country IMF quotas, relief for those in need of reserves will come as an excess in other cases.

The SDR value is calculated daily by the IMF based on a basket of international currencies which, in fixed proportions, currently includes the US dollar, Japanese yen, euro, pound sterling and Chinese renminbi. The composition of the basket is reassessed every five years.

SDRs are an asset that simultaneously pays and charges interest. It all depends on the balance between the allocations received by the country and their use. If a country does not use its SDRs, interest income and payments outweigh each other, and the cost is zero.

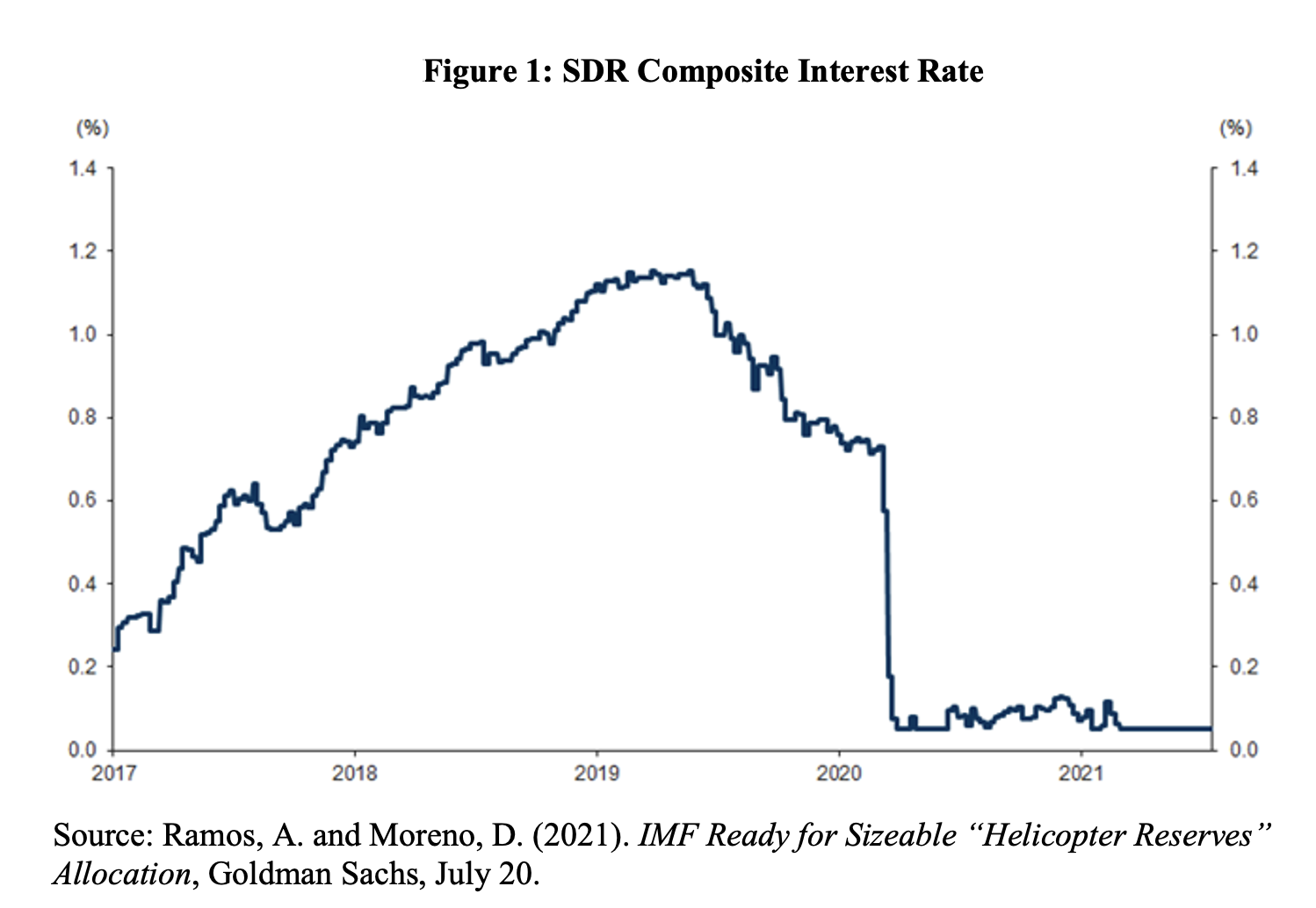

The SDR interest rate is set weekly as a weighted average of interest rates on short-term government bonds in the money markets of the countries of the basket. It is currently at its floor: 0.05% (Figure 1). At least in the case of non-advanced economies, it is still below the rates charged by the markets.

There is, therefore, even a potential pecuniary advantage to using SDR to redeem other external debts. Everything depends, however, on institutional arrangements within countries, particularly regarding who holds foreign reserves and manages foreign exchange flows, and the transfer of resources from central banks to the Treasury. In about 70% of countries, central banks are the SDR recipients, while in the U.S., for example, SDR assets and liabilities are recorded on the government balance sheet.

President Lopez Obrador of Mexico, for example, has already referred to using the opportunity to prepay external public debt. Although local law does not allow transfers from the central bank to the executive, the government can acquire reserves other than SDR if it holds balances in Mexican pesos with the central bank, as part of public debt management. Basically, this would result in an exchange of hard currency reserves for the added SDRs.

China has added another $41.6 billion to its already high reserves, Brazil another $15.1 billion and 35 advanced economies another $399 billion. On the other hand, the arrival of reserves in the form of SDRs will be extremely welcome and will give some breathing space to countries including Argentina, Ecuador, and El Salvador in Latin America, and several countries in other regions (Sri Lanka, Zambia, Liberia, etc.). Venezuela will receive its allocation, but without unconditional access, given that the Maduro government is not recognized as legitimate by more than 50 member countries, including the largest shareholder, the U.S.

The increase in reserves globally will not have a great impact, being equivalent to something around 0.7% of the world GDP. However, it will provide a lifeline, temporary or not, for countries facing low reserves and high external financing requirements.

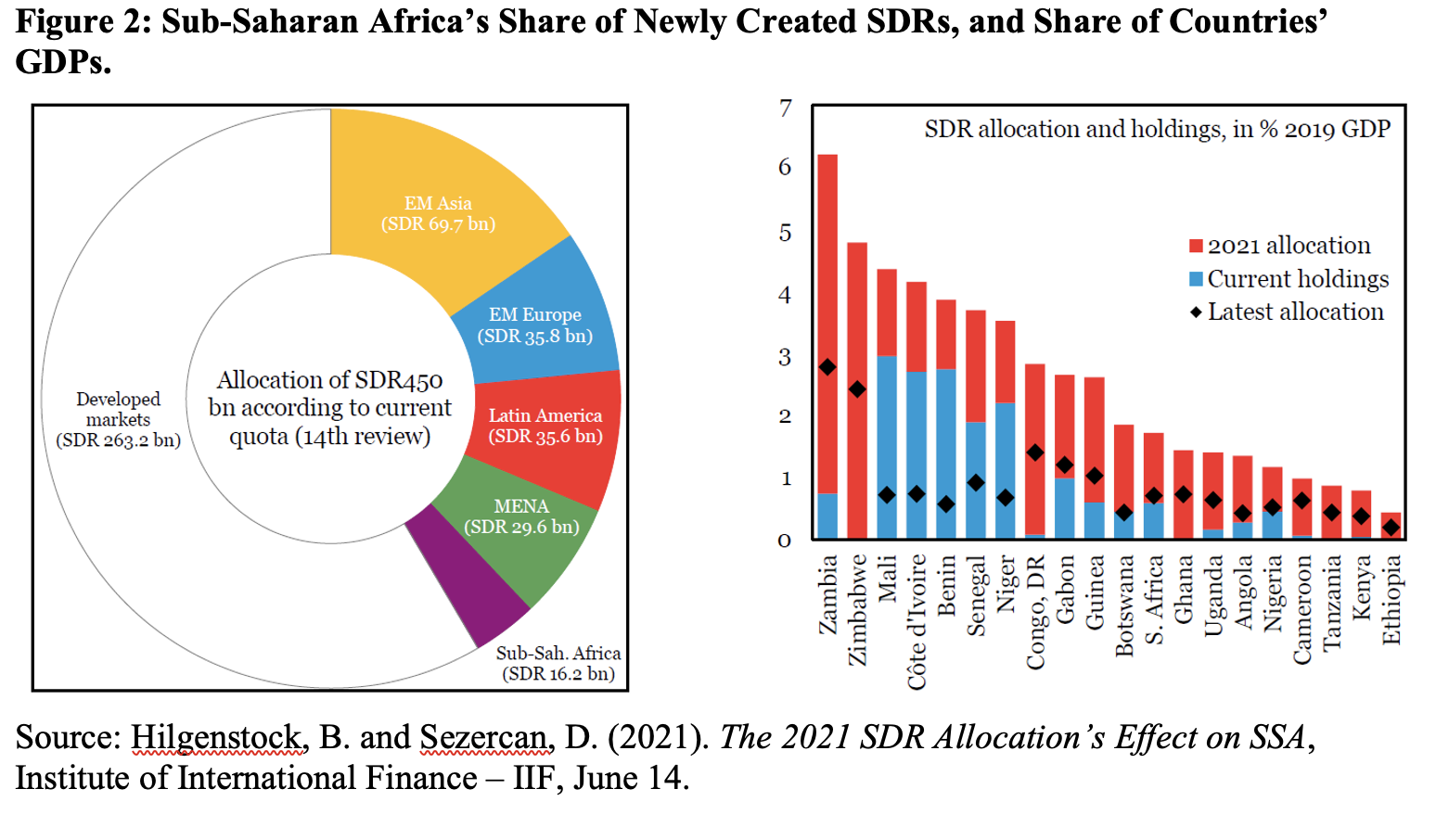

Sub-Saharan Africa received a small share of the newly created SDRs (Figure 2, left side). However, these amounts will be substantial as a share of GDP in some cases (Figure 2, right side).

As a next step, the IMF has set out to find ways in which countries with SDR surpluses can voluntarily channel them to those in need. For example, they can be lent to the fund that the IMF uses to make concessional loans to low-income countries (Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, PRGT), or to another fund to be created to help more vulnerable countries undertake structural transformations, including adaptation to climate change (Resilience and Sustainability Trust, RST).

Surplus SDR could also be channeled to support lending by multilateral development banks and even given as donations to the concessional arm of the World Bank: The International Development Agency (IDA). The development impact of the SDR allocation can be magnified. The fact is that creation of SDR following IMF quotas provided a very small share for low-income countries (69 economies that will receive US$21.2 billion), while they are precisely the most negatively affected by the crisis, with slower vaccination rates and the worst debt problems.

As noted in a report by Alberto Ramos and Daniel Moreno (Goldman Sachs, July 20), the increase in SDR stocks does not automatically correspond to an increase in the money supply in the global economy. The use of SDR only transfers hard currency from one country to another, with corresponding changes in the composition of reserves. There will only be such an increase in the money supply if the central bank that issues the hard and convertible currency granted in exchange for the SDR does not sterilize its monetary impact.

SDRs, therefore, do not constitute money thrown from a helicopter, as in the famous image used by Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman in 1969, and cited in Ramos and Moreno's Helicopter Reserves report. But one cannot deny that this allocation fell from the sky at a good time for economies struggling with a shortage of reserves and with immediate needs for external financing.

The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author.