Publications /

Opinion

Camila Crescimbeni is a 2023 alumna of Atlantic Dialogues Emerging Leaders program. Learn more about her here.

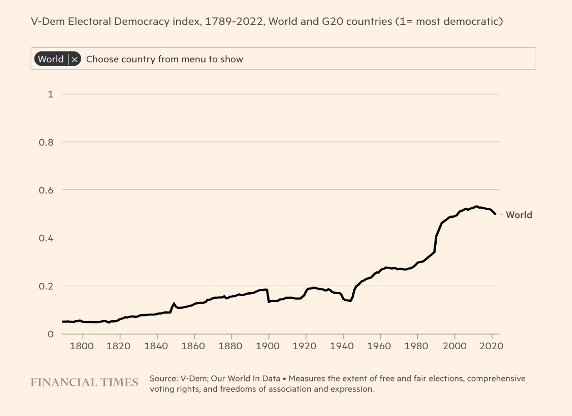

Following a fruitful and broad debate at the 2023 Atlantic Dialogues, Alec Russell, foreign editor of the Financial Times, asked a deep and globally-relevant question: Can democracy survive 2024? With 70 states having elections this year, it is a fundamental question. After some decades of continuous expansion of democracy worldwide, as shown by the V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index, there now seems to be a downturn. Is this a surprising trend or is there an underlying risk in all democratic societies?

V-Dem electoral democracy index as portrayed in Alec Russell’s article ‘Can Democracy survive 2024?’ https://www.ft.com/content/077e28d8-3e3b-4aa7-a155-2205c11e826f

A visionary on the uncertain path of democracy, French philosopher Claude Lefort argued that inherent to democracy’s design is its own antidemocratic demon: uncertainty. After the fall of absolute regimes in the West and, with them, the belief in a transcendent fundament[1] of the political order, societies began looking for a new foundation. With the rise of liberal democracies, the foundation of society became immanent instead of transcendent: God was no longer the reason and end behind everything, it was common people who had to bear the responsibility of everything that went right or wrong. It was the dawn of Illuminism and Modernity, with much hope in anthropocentrism.

But the nature of democracy itself has its Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Lefort reflected, since the lack of an absolute foundation can make people scared of uncertainty and instability, and lure them into cherishing a stronger and more predictable way of things. Lefort called this “the phantom of People-One” (in French, le people-Un), a concept he took from Etienne de la Boétie, whereby he referred to the desire he identified within human beings to have an ultimate and irrefutable foundation on which to blame all wrongs and where to find all rights. Living in a democratic society, for Lefort, entails developing a joy, or at least a tolerance, for uncertainty, dynamism, and instability. No one is the owner of the place of power, no one is the State à la Louis XIV, no one can claim to hold together the fabric of society. We only have temporary occupants of power who always represent part of it, but those occupants are not society. Absolute representation is just an oxymoron.

In this sense, we have to be able to train our people for the kind of system we all chose as the best available. For democracies to work and prosper, open societies are needed rather than closed societies; people should enjoy and celebrate diversity and not resent it; children and young people must be able to believe they can prosper despite, or rather through, dynamism. However, the wave seems to be going the opposite way, and this harms democracies and people’s expectations of how democracy can bring about development, not generally speaking, but for them. We are growing scared of each other, seeing our fellow citizens as potential competitors or rivals, and not finding a significantly happy reason to live together. We are looking for institutions or leaders or devices that promise fast and easy and absolute truths, relieving our fear of constant change. Many don’t find their place in society now, not even as an expectation that after a certain pathway of hard work and effort they will belong, and this has placed an underlying strain on the way we thought democracies would continue to spread.

Hopefully 2024 will bring about discussions in the 70 states holding elections and elsewhere, through which we can focus not so much on being right but on being helpful, to move towards a happier, more tolerant, and fairer world order.

[1] According to Lefort (and many post foundationalists), a transcendent fundament is the opposite of an immanent fundament. A transcendent fundament of society is outside society itself (e.g., God), and no one can challenge it. On the contrary, an immanent fundament refers to the origin and basis of society as coming from within society itself.