Publications /

Opinion

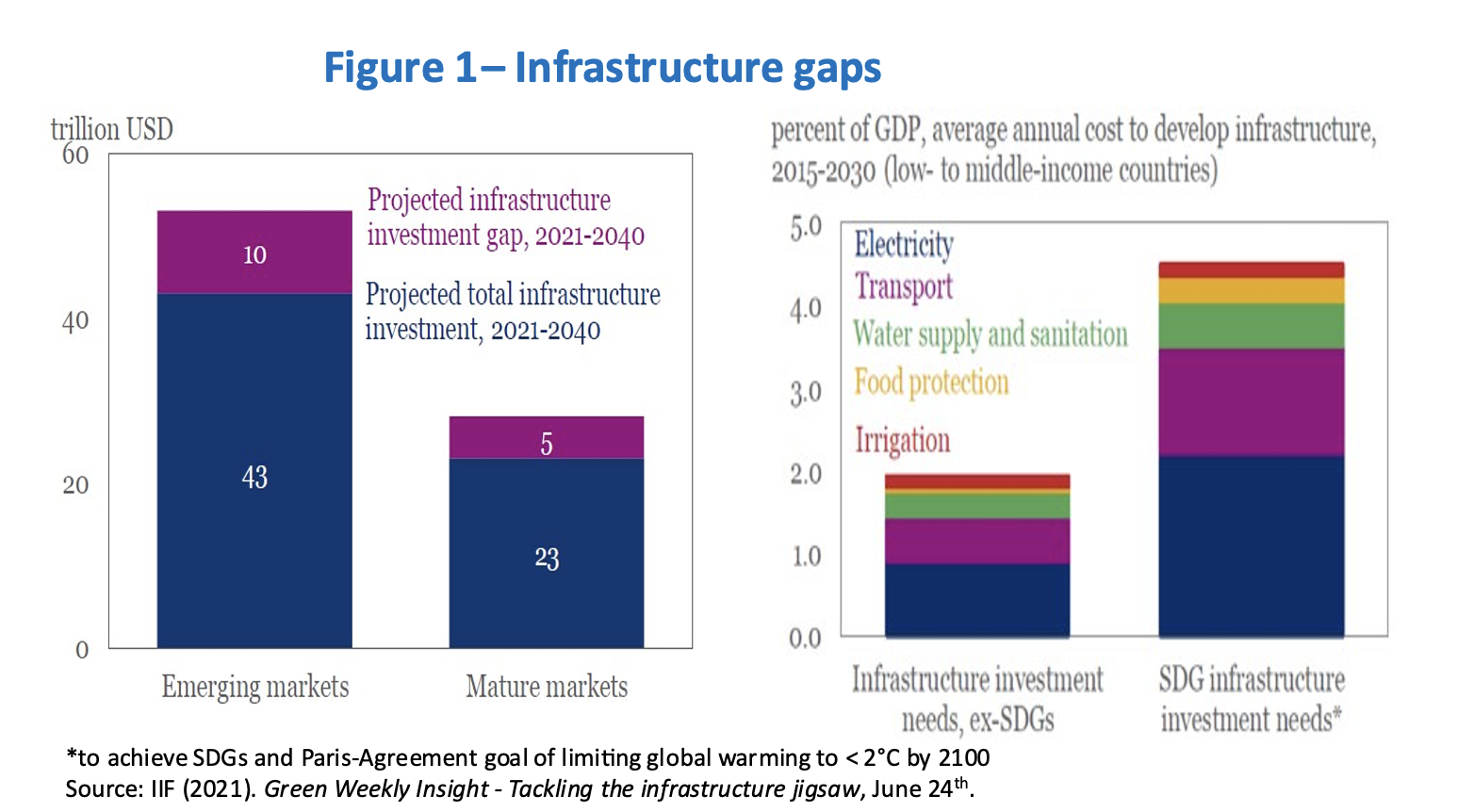

The world faces a huge shortfall of infrastructure investment relative to its needs. With a few exceptions, such as China, this shortfall is greatest in emerging and developing countries.

The G20 Infrastructure Investors Dialogue estimated the volume of global infrastructure investment needed by 2040 to be $81 trillion, $53 trillion of which will be needed in non-advanced countries. The Dialogue projected a gap—in other words, a shortfall in relation to the investment needs foreseen today—of around $15 trillion globally, of which $10 trillion is in emerging economies (Figure 1, left panel). The World Bank has estimated that, for emerging and developing economies to reach the Millennium Development Goals set for 2030, their infrastructure investment would have to correspond to 4.5% of their annual GDPs (Figure 1, right panel).

In addition to the need for infrastructure investment, there is a need for that investment to be ‘greened’ as rapidly and extensively as possible, in order to minimize the negative impact in terms of increased global warming. For example, the energy sector must be decarbonized by expanding the use of renewable sources instead of coal. Increases in use efficiency, and the elimination of subsidies for the use of fossil fuels, would be part of this strategy.

Transport is now responsible for 25% of the world's greenhouse-gas emissions. This must be reduced by shifting transportation to low-carbon options, in addition to investments in energy-efficient equipment, and supporting the transition to electric vehicles and fleets.

A major part of the ‘greening’ will be in cities: improved water supply and sanitation services, changes in energy supply, waste recycling, and greater energy efficiency through better building standards and/or renovation of existing buildings. This transition, as for manufacturing and agricultural activities, will require investment in infrastructure.

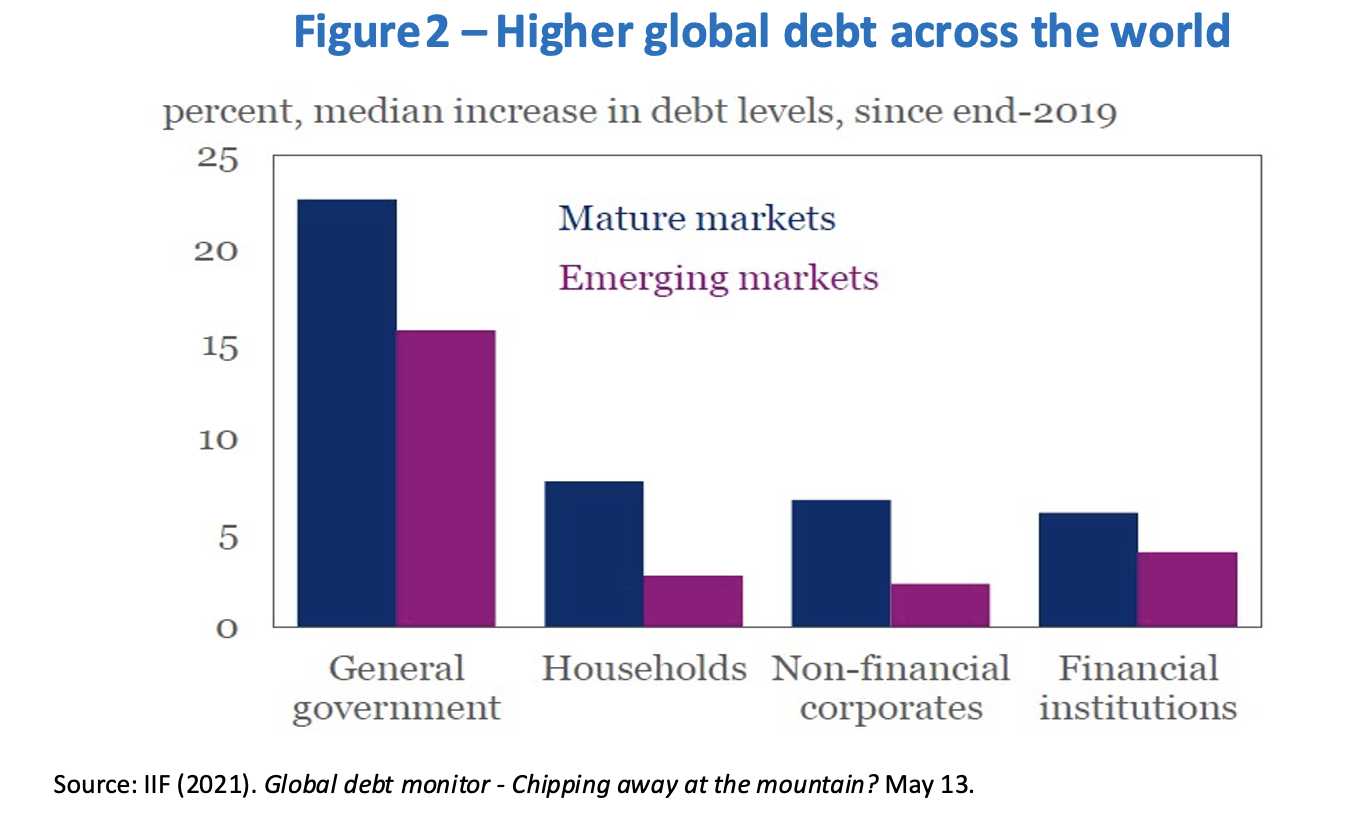

A major obstacle holding back such investment is the lack of fiscal space, which is constraining public spending. This problem has been made worse by the fiscal packages adopted because of the pandemic. While the largest advanced economies can afford to increase their public debt, with a low risk they will face deteriorating financing conditions, this does not apply to most emerging economies, let alone low-income countries grappling with unsustainable debt trajectories (Figure 2).

Consequently, measures need to be taken to expand the options for private financing of infrastructure projects. Indeed, according to data from the Institute of International Finance, over the past 15 years, institutional investors with long time profiles in their assets, such as pension funds, have been gradually increasing their allocations to infrastructure investments and alternatives to fixed income instruments, equity, and other traditional instruments.

Stable and long-term returns from infrastructure projects dovetail well with the long-term commitments of those financial institutions, particularly in the context of declining long-term real interest rates on public and private bonds, as seen in recent decades in advanced countries. Surveys carried out by Preqin show fund managers already pointing to the decarbonization of energy as a factor in attracting private investment to infrastructure.

The biggest challenge is to build bridges between, on the one hand, infrastructure investment needs in non-advanced countries and, on the other, private sources of finance abundant in dollars and other convertible currencies with few opportunities to obtain returns compatible with their requirements on their liability side.

Building such bridges requires the completion of two tasks. First, the development of properly structured projects, with risks and returns in line with the preferences of the different types of financial intermediation, would help close the private financing gap in infrastructure.

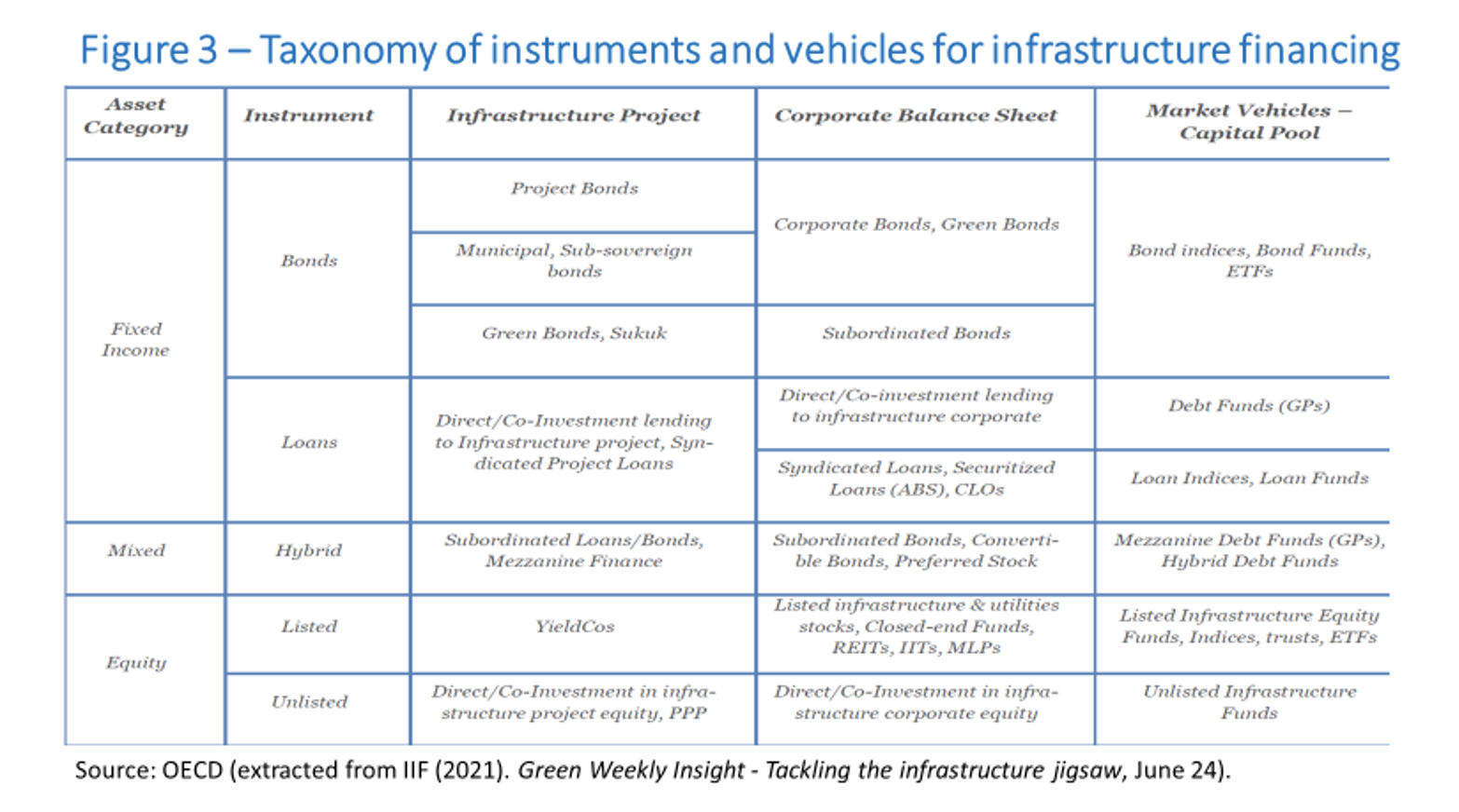

Investors have different mandates and skills regarding the management of risks associated with types of projects, and phases of project investment cycles. They demand coverage of risks whose exposure is not adequate or permitted by regulation. The absence of complementary instruments or investors is one of the most frequently identified causes of failure in the financial completion of projects. Figure 3 provides a snapshot of the diversity of instruments and vehicles through which private finance can participate in infrastructure projects.

The constrained fiscal space in emerging and developing countries can be used to mainly cover such risks and enable the building up of investment, rather than replacing private investment: crowding-in private finance rather than crowding it out. National and multilateral development banks could prioritize this instead of financing total investments.

Identifying attractive investment opportunities for different types of investors and combining these perspectives more systematically around specific projects or asset pools is a promising way to fill the infrastructure financing gap. The planning and integrated issuance—with different time profiles—of fixed-income securities, bank loans, credit insurance, and others, for the different phases from project preparation to operation, make that combination possible.

The second task to boost private infrastructure investment in emerging and developing economies is the reduction of legal, regulatory, and political risks. Transparency and harmonization of rules and standards can increase the scale of comparable projects and make it possible to build project portfolios. Non-banking financial institutions often highlight the absence of large enough project portfolios as a disincentive deterring the setting up of business lines focused on the area. This is a particular weakness in the case of smaller countries.

The contrast between the scarcity of investments in infrastructure—particularly in non-advanced economies—and the excess of savings invested in liquid and low-yield assets in the global economy deserves to be confronted. Greening infrastructure in non-advanced economies would benefit from being able to attract greenbacks into the business.

Watch Bridging Private Finance and Green Infrastructure

The contrast between the scarcity of investments in infrastructure – particularly in non-advanced economies – and the excess of savings invested in liquid and low-return assets in the global economy deserves to be confronted. Greening infrastructure in non-advanced economies would benefit from being able to attract greenbacks into the business. Building a bridge between private finance and (green) infrastructure would need the development of pipeline of projects with homogeneous regulations and standards, as well as with minimum mismatch between risks and comfort of private investors to manage them along project stages.