Publications /

Opinion

After a strong rising tide starting in the 1990s, financial globalization seems to have reached a plateau since the global financial crisis. However, that apparent stability has taken place along a deep reshaping of cross-border financial flows, featuring de-banking and an increasing weight of non-banking financial cross-border transactions. Sources of potential instability and long-term funding challenges have morphed accordingly.

Financial globalization is morphing after its recent peak

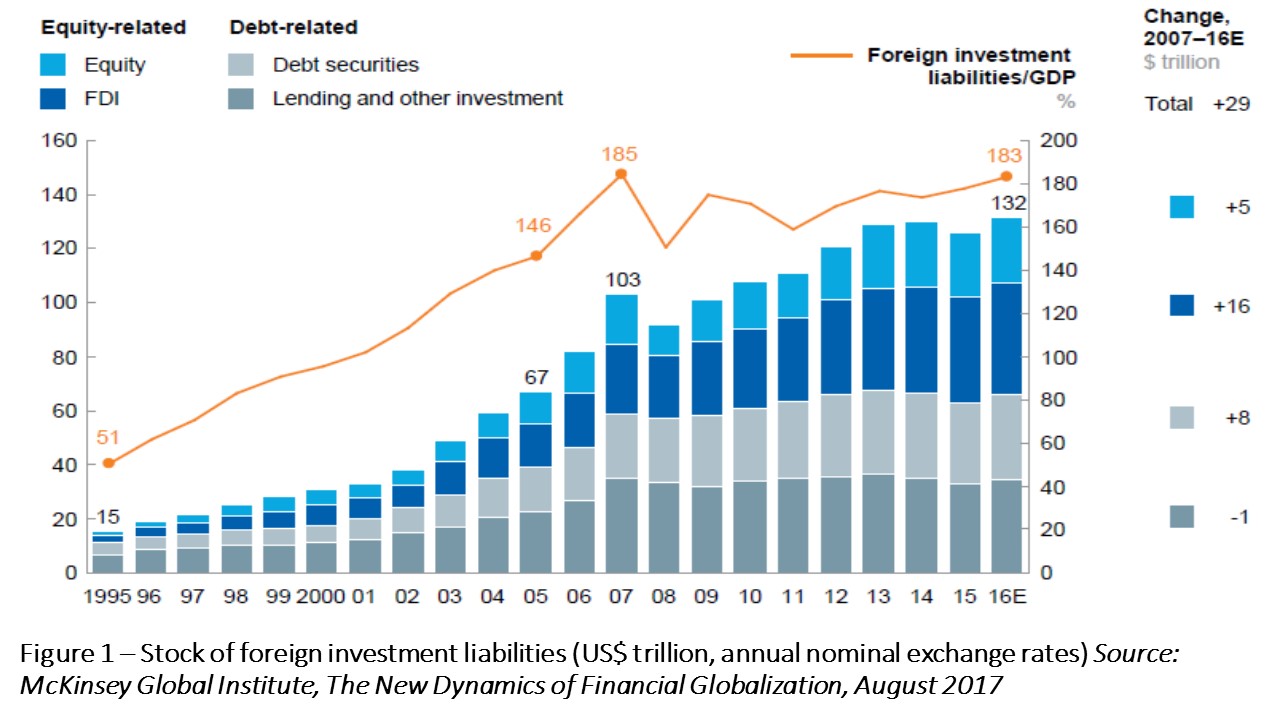

Financial globalization – as measured by the ratio of the stock of foreign assets to world GDP ¬- seems to have reached a plateau since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) (figure 1). Post-2007 ratios seem to have been the apparent “peak” of a high wave of financial globalization rising from the mid-1990s, which likewise saw external financial assets and liabilities soaring and degrees of financial openness reaching levels triple the ones of before World War 2.

Along with the deceleration of the pace of rise of stocks relative to world GDP, a change of composition in flows has taken place, as also depicted in figure 1. While total cross-border lending decreased as a proportion of GDP, the stable level of global ratios of foreign liabilities to GDP occurred because of increased flows of foreign direct investment (FDI), equity portfolio and debt securities. Such aggregate figures, however, gloss over some relevant features in detail.

Financial globalization has mainly happened among advanced economies

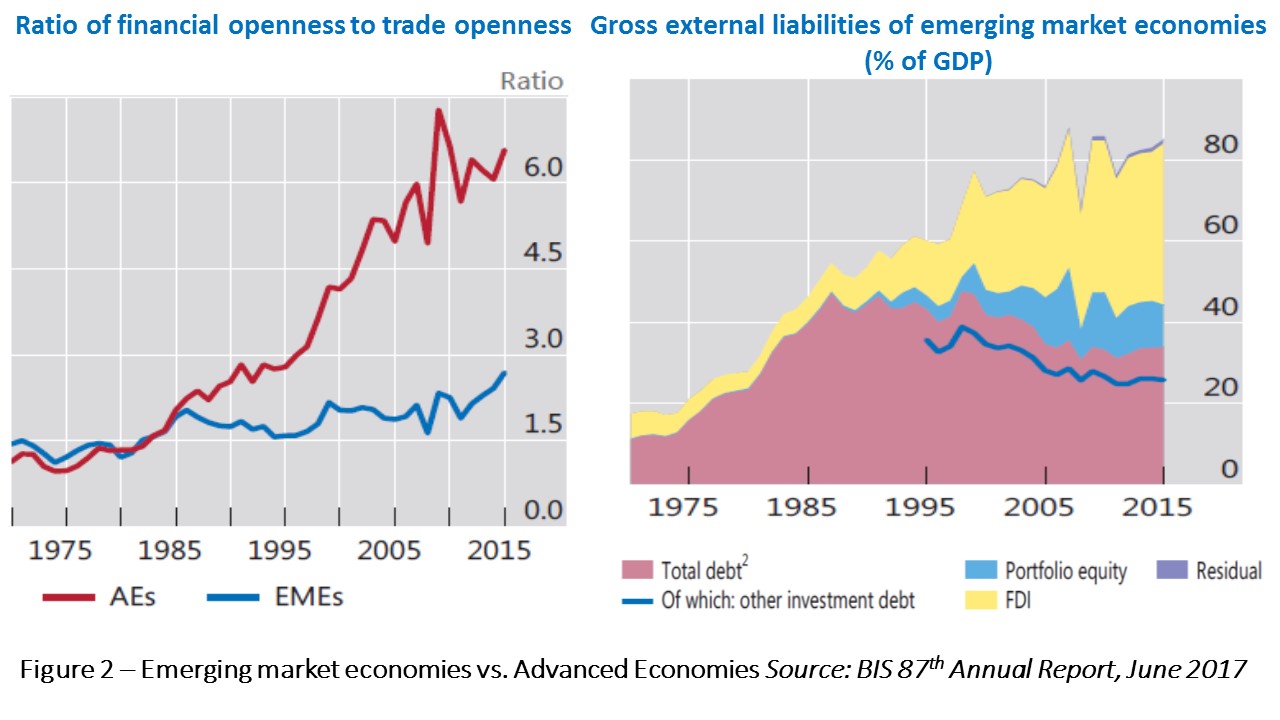

Rising cross-border movements of financial assets from the mid-1990s has been remarkable among advanced economies (AEs). Levels of financial openness (the sum of foreign assets and liabilities as a proportion of GDP) relative to trade openness (the sum of exports and imports as a proportion of GDP) were similar on both groups of advanced and emerging market economies (EMEs) until mid-1980s but shifted upward in the former’s case, rising rapidly particularly since mid-1990s (figure 2, left side). Cross-border financial assets and liabilities went from 135% to above 570% of GDP since mid-1990s for AEs, whereas they moved from approximately 100% to 180% of GDP on the side of EMEs (BIS, 2017).

In general, two major processes lead to rising cross-border financial transactions. First, there is a mutually reinforcing association with increases in foreign trade and production. Even if foreign trade corresponds simply to movements of commodities and finished goods, basic international financial links – e.g. trade finance and cross-border payments - are pulled on. Such a connection only increases with the emergence of cross-border value chains and foreign investment of corporations abroad, which lead to acquisition of assets and liabilities and corresponding management of exposures.

In addition to financial operations derived from trade and production relations, the active management of balance sheet positions may also lead to cross-border financial transactions as part of the processes of allocation and diversification of savings. As remarked by the BIS (2017), such purely financial processes bring some “decoupling between real and financial openness”.

Financial liberalization and sophisticated banking and financial markets in AEs created conditions for a surge of foreign transactions of assets as illustrated in both figures 1 and 2 (left-side). Financial openness also rose faster than trade openness in EMEs, albeit at a much slower pace.

It is worth highlighting the changes in the composition of EMEs gross liabilities, with declines in foreign debt being more than compensated by portfolio equity and foreign direct investments – FDI (right-side, figure 2). The global rising share of non-lending financial transactions exhibited in figure 1 was particularly accentuated in the case of EMEs.

European banks have been at the core of both surge and pause of the wave of financial globalization since the 1990s

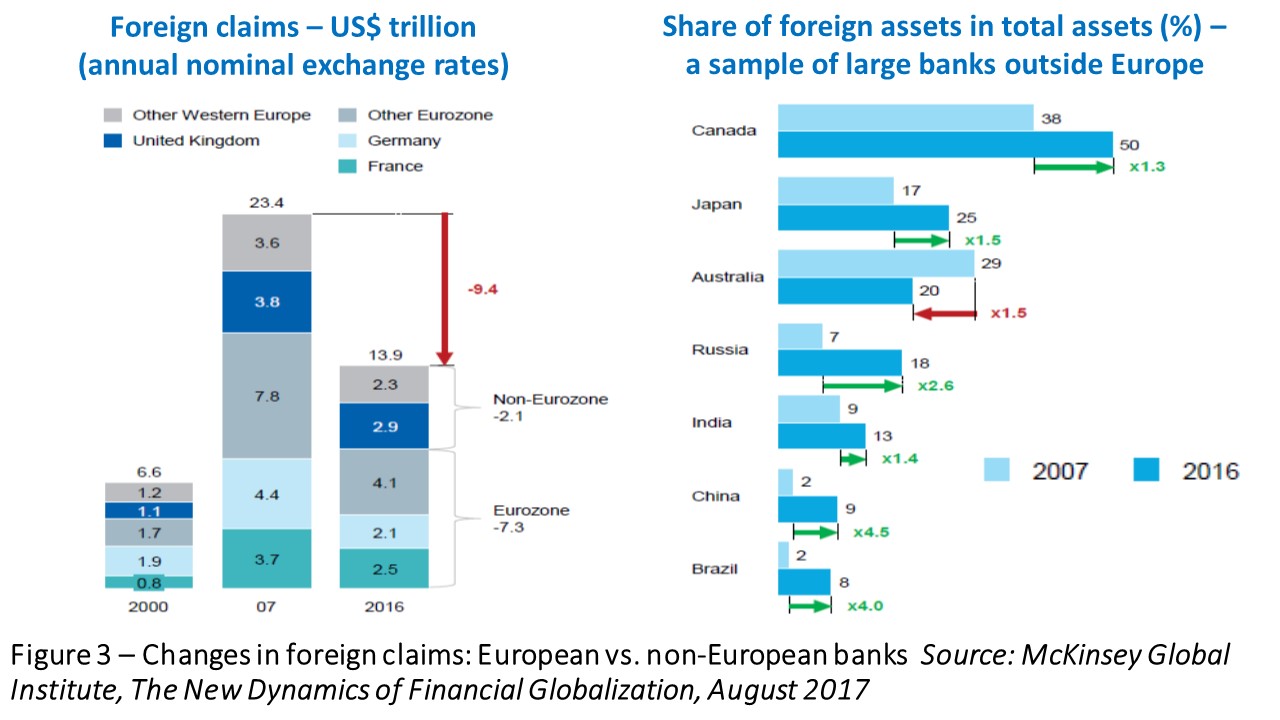

Figure 3 (left-side) shows the substantial piling up of European banks’ foreign claims in the run up to the GFC, followed by an also substantial retrenchment. The right side illustrates how some banks outside Europe have partially occupied the space left by their European counterparts.

Lending by European banks was behind two of the major contributing factors to the rising wave of financial globalization. First, the inauguration of the Euro, followed by markets initially converging their assessments of risk premiums across the zone downward toward German levels, boosted cross-border transactions. According to the BIS annual report released last July:

“Between 2001 and 2007, 23 percentage points of the increase of the ratio of advanced economies’ external liabilities to GDP was due to intra-euro area financial transactions and another 14 percentage points to non-euro area countries’ financial claims on the area (p.102).”

Furthermore, European banks also played an active role in the asset bubble-blowing process in the U.S. financial system. As tackled in studies by Hyun Song Shin, Claudio Borio and others, European banks used U.S. wholesale funding markets to sustain exposures to U.S. borrowers through the shadow banking system. Despite their small presence in the domestic U.S. commercial banking sector, their weight on overall credit conditions was magnified through the shadow banking system in the United States that relies on capital market-based financial intermediaries which intermediate funds through securitization of claims.

From the standpoint of the balance-of-payments between the U.S. and Europe, those transactions netted out. Nonetheless, from an accounting sense they represented short-term borrowing combined with long-term lending by European banks, with a corresponding double counting as cross-border financial transactions.

The retrenchment of European banks’ foreign claims followed both the U.S. asset-bubble burst starting in 2007 and the Euro-zone crisis 2009 onward. Besides business-driven reasons – losses, decisions to deleverage balance sheets – tighter banking regulation and the orientation toward domestic assets assumed by post-crisis unconventional monetary policies also weighed. These factors have also led to deleveraging, balance-sheet shrinking, and domestic reorientation by banks in the other crisis-affected AEs. Although some banks from outside the latter have expanded their foreign lending, levels of global financial openness have been maintained thanks to growing flows of non-lending instruments (debt securities, portfolio equity and FDI).

The apparently higher stability of global finance may conceal other fragilities

As highlighted by a recent report from McKinsey Global Institute (2017), some features of “the new dynamics of financial globalization” may embed in it higher stability. Higher capital buffers and minimum amounts of liquid assets have reduced the weight of bank lending and the intrinsic features of mismatch and volatility of banks’ balance sheets. The higher share of equity and FDI, in turn, may carry longer-term return horizons and closer alignment of risks between asset purchasers and originators. The unwinding of debt-financed huge current-account imbalances characteristic of the global economy in the run-up to the GFC has also contributed to such a view of global finance entering a less unstable phase.

However, flows of FDI partially correspond to disguised debt flows and/or transfers motivated by tax arbitrage or regulatory evasion (Blanchard & Acalin, 2016). Cross-border debt flows – including securities - in turn, are also sensitive to global factors, besides carrying a high sensitivity to and procyclicality with respect to monetary-financial conditions in either source and/or destination countries.

There are also “blind spots” left by de-banking hitherto not preempted by non-banking financial transactions. For instance, cross-border de-risking by global banks has entailed closure of correspondent banking relations in many countries in which the paucity of alternatives has led to negative consequences to the local financial dynamics (Canuto & Ramcharan, 2015). By the same token, the arms-length distance between asset holders and liability issuers intrinsic to debt securities and portfolio equity, in the absence of the project-finance role played in the past by international investment banks, often constrains the cross-border financing of greenfield investment projects to FDI possibilities (Canuto, 2014) (Canuto & Liaplina, 2017).

It is also worth referring to the potential transformative impact – and corresponding need for regulatory adaptation – on cross-border finance brought by digital technologies. We may well be on the brink of an additional metamorphosis of global finance and the instability that may come with it.

Bottom line

The transformation of global finance has not suppressed the need for policies to monitor and cope with risks. On the side of recipients of net capital inflows, domestic agendas of institutional strengthening to reinforce alignment of risks between investors and countries, together with regulatory vigilance against excess financial euphoria or depression remain necessary. The bar in terms of domestic institutional quality – corporate governance standards, business environment – has been raised in the new phase of global finance.