Publications /

Opinion

In previous pieces, we have analyzed the run up to the still-ongoing Brazilian recession as a combination of factors. Given an “anemia” of productivity increases, an appetite for public spending without prioritization led to a condition of fiscal “obesity”. The external factors that provided for a boom in the new millennium, notwithstanding underlying vulnerabilities, have dissipated. The economic policy adopted as a response to the growth decline aggravated those vulnerabilities. On top of those, a disruption of existing large domestic corporate structures followed broad corruption investigations (Canuto, 2016a) (Canuto, 2016b) (Canuto, 2016c).

Here, with the help of five charts, we touch on another dimension of Brazil’s economic boom and bust, namely, a credit cycle, the downward phase of which helps understand why the post-crisis recovery has been so hard to obtain. In our view, the profile of such a credit cycle in effect points to it as a special chapter of our previously approached determinants of the Brazilian economic crisis.

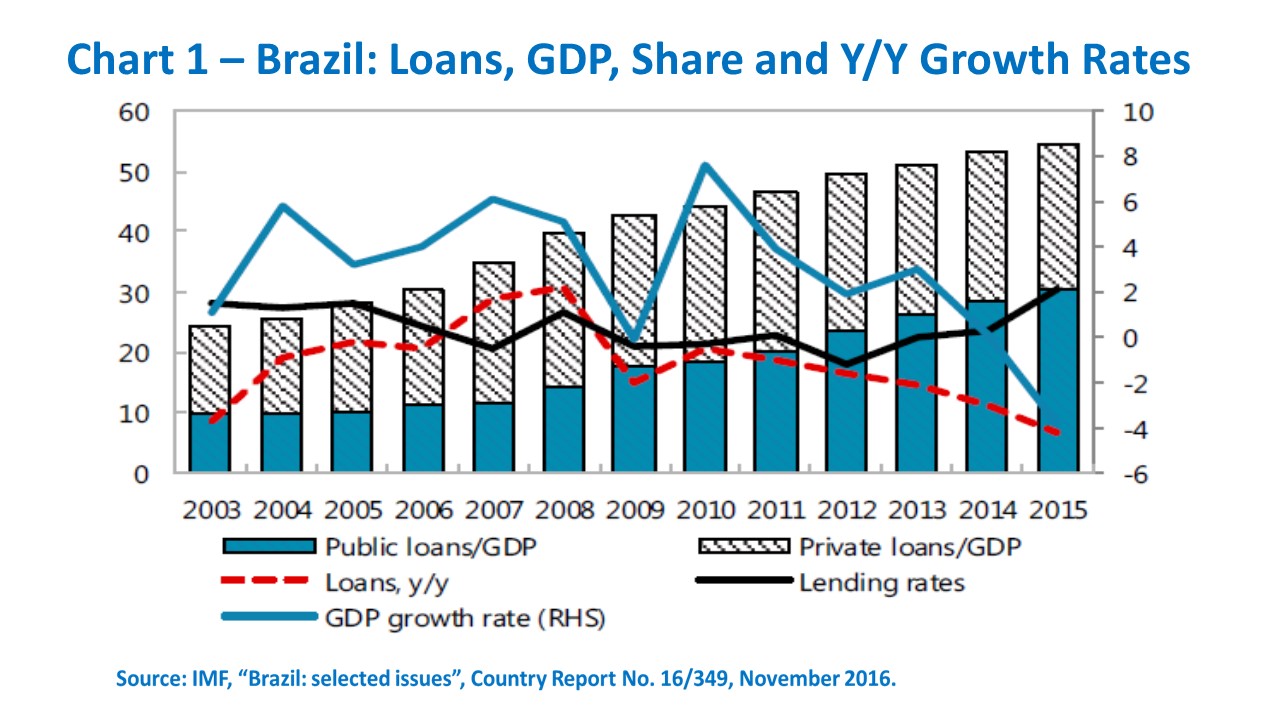

Brazil’s economic boom of 2004-2013, during which only a short and shallow recession occurred in 2009 and annual GDP growth averaged 4.5%, benefitted from a positive feedback loop with a credit surge (Chart 1). Total credit to the private sector more than doubled as a share of GDP from 2003 to 2015, rising roughly 30 percentage points.

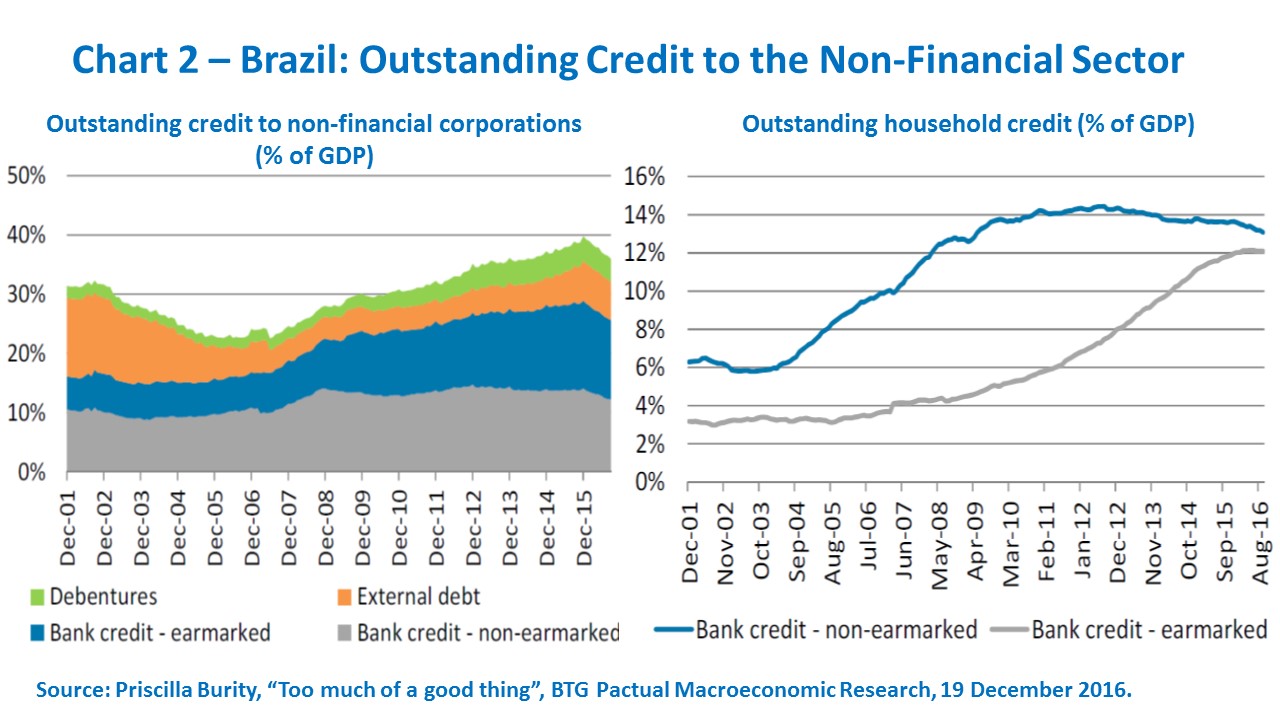

We see Peculiar features of the credit surge in Chart 2. Notice the rising weight of earmarked bank credit to both non-financial corporations and households from 2008 onwards, including keeping the overall stability of the latter after 2010. In passing, observe that the non-financial corporation relative exposure to external indebtedness and debenture issues seems to be lower than in other comparable emerging markets (Canuto, 2015).

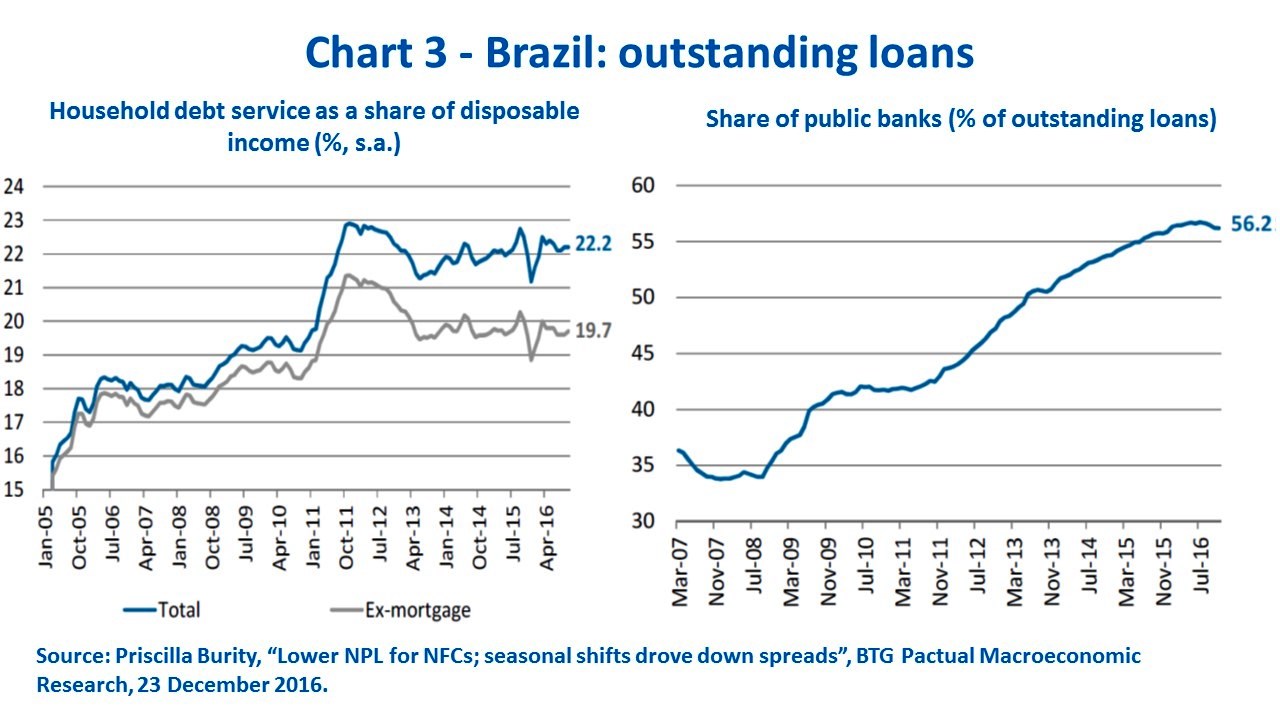

The relative stability of overall household debt levels since 2011 has a counterpart on its service as a share of disposable income, as displayed on the left side of Chart 3, with mortgage payments partially occupying the space of other types of debt service. Furthermore, the rising role played by public banks – including the official major development bank (BNDES) - in sustaining the earmarked-credit pillar of loan expansion, especially 2012 onwards, can be visualized on the right side of the same chart.

Prior to 2008, rising shares of credit to GDP to a large extent reflected its elasticity to growth as well as structural reforms and innovations leading to financial deepening (e.g., payroll bill loans, legal enhancement of collaterals). From 2011 onwards, in turn, they primarily reflected the government policy of responding to the loss of GDP dynamism by stepping up earmarked credit through public debt-funded transfers to public banks: BNDES lending directly and through on-lending via other banks to non-financial corporations; the two largest government-owned commercial banks providing higher amounts of rural credit and residential housing finance.

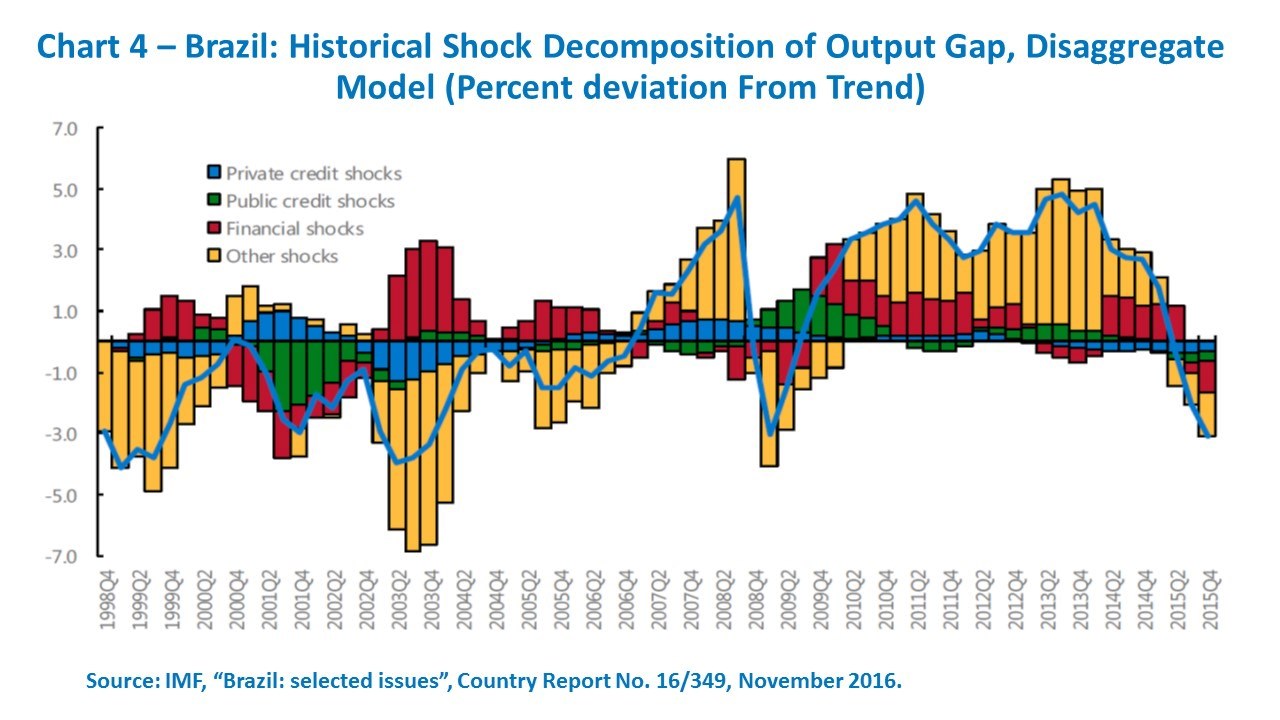

That also comes out in the IMF study of financial and business cycles in Brazil released last November – see IMF (2016). When examining macro-financial linkages, they decompose Brazil’s output gap evolution between 1999 and 2015, as depicted in Chart 4. The study remarks (p.12-13):

“Private credit boosted output in the lead up to the global financial crisis and public credit boosted output following the crisis. Strong growth in private credit in over 2005 to 2008 acted to support output. When the crisis hit in late 2008, private credit growth began to slow as private banks acted to bolster their balance sheets. At the same time, public credit was expanded in an effort to support demand after the crisis, providing a boost to output over 2009‒10. The impact of the slowdown in private credit growth can be seen in the drop in importance of private credit shocks towards the end of 2008. Likewise, public credit went from being broadly neutral for growth in the lead up the crisis to being strongly expansionary.”

Financial shocks in the chart are measured using an indicator of financial conditions combining money market spreads, collateral values (stock prices, house prices), total credit, interest rates, and external financial conditions (EMBI, real exchange rate). It captures and partially reflects changing external financial conditions, positive from 2009 to 2013, while turning negative following the taper tantrum and a hike in foreign funding costs.

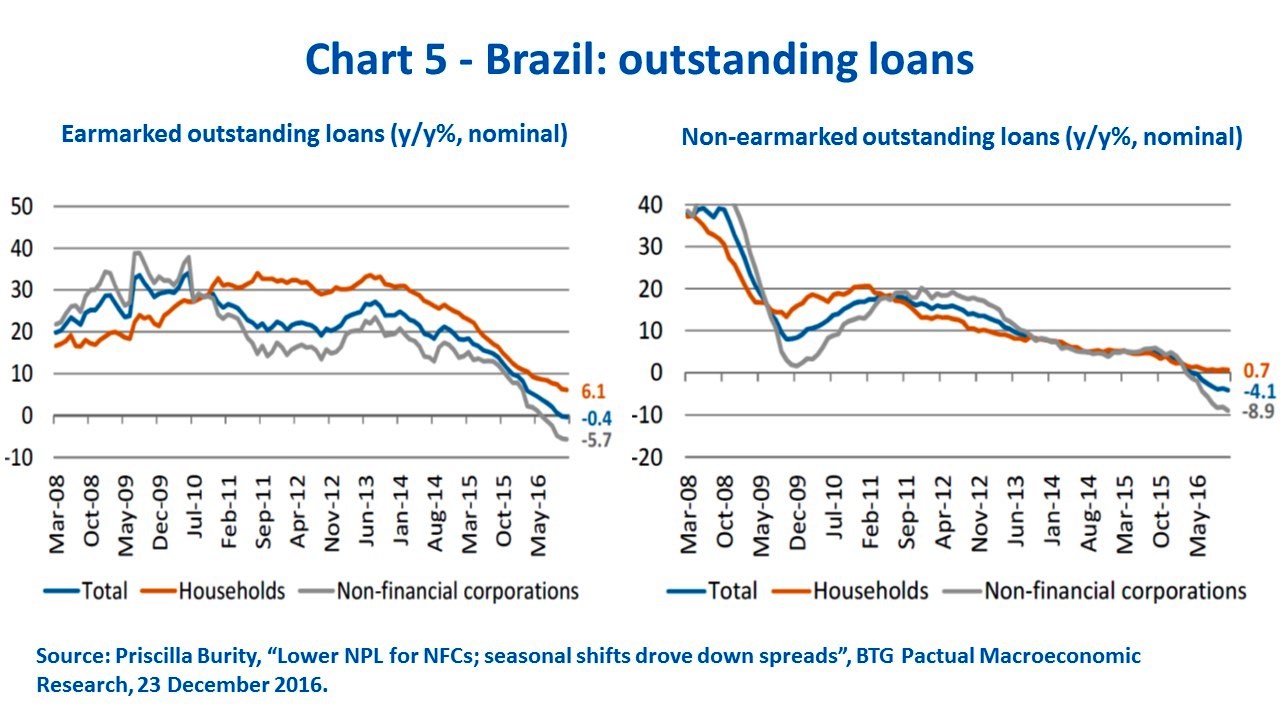

The decomposition in Chart 4 also shows how, more recently, public and private credit and financial conditions all converged pulling output downward. While private credit started contracting first, public credit moved south since early 2015, when fiscal considerations led to curbs on the expansion of public debt-funded lending by public banks. Chart 5 exhibits the beginning of debt deleveraging from the standpoint of annual rates of increase of earmarked versus non-earmarked outstanding loans. Non-earmarked credit never fully recovered its pace of before 2008, and kept a downward trend until starting to unwind more recently. Earmarked outstanding loans, in turn, held a high speed until 2014 but began reversing until beginning to shrink in the case of non-financial corporations.

Let me suggest the following takeaways:

1. The Brazilian economy has indeed gone through a full credit cycle, and it is currently on its downward phase. Positive feedback loops between finance and macroeconomic activity turned negative in this stage, as deleveraging of balance sheets is imposed or pursued on both supply and demand sides of finance.

2. However, this is no macro-financial-cycle business as usual. Instead of pure “animal spirits” or any type of Hyman Minsky’s “endogenous financial instability” created by private agents jointly willing to skyrocket leverage, it acquired a “fiscal” nature after 2011. Its extension and depth cannot be understood without taking into account the issuance and transfer of public debt from the Treasury to public banks, as a component of pro-active fiscal and industrial policies (Canuto, 2013). Ultimately its halt was dictated by fiscal policy considerations.

3. As a strongly policy-driven cycle, embedding subsidies, it led to private sector indebtedness likely above those levels that would stem from the elasticity of credit to GDP and structural determinants of financial deepening. In a recent note, Priscilla Burity, from BTG Pactual, estimates a peak of private sector credit close to 40% of GDP as a reference for that matter (“Too much of a good thing”, BTG Pactual Macroeconomic Research, 19 December 2016).

4. Given structural determinants unfavorable to higher overall levels of private investment – which we have approached in Canuto (2013) and Canuto (2016c) - , it became one of those “investment-less credit booms” mentioned by the World Bank in chapter 3 of its newly released Global Economic Prospects, January 2017. Subsidies associated with earmarked credit seem to have induced more of a debt substitution than an overall increase of investment.

5. Monetary policy effectiveness was negatively affected by the fact that the credit channel of transmission received contradictory impulses. Furthermore, given that banks tend to compensate costs derived from earmarked credit via higher spreads in non-earmarked lending, the relationship between basic interest rates and financial costs became increasingly distorted. On the other hand, given the absence of any fiscal space for government-sponsored balance sheet fixing, hopes for a smoother deleveraging process are now relying mostly on loosening of monetary policy – which has started after finally inflation converged toward its target.

All in all, when looking closer to the Brazilian recent financial cycle and the so-called “balance-sheet recession”, we find those same diseases that we approached in previous pieces.