Publications /

Opinion

Sudan’s Heritage: Looting as a Weapon of War

Sudan, in addition to the political and humanitarian crisis that has shaken the country for years, is now facing a worrying degradation of its cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible, particularly in areas where the fighting is most intense. Cultural heritage has become another victim of this war: the destruction of archaeological sites and the looting of museums fuel the illicit trafficking of cultural property and contribute to regional instability.

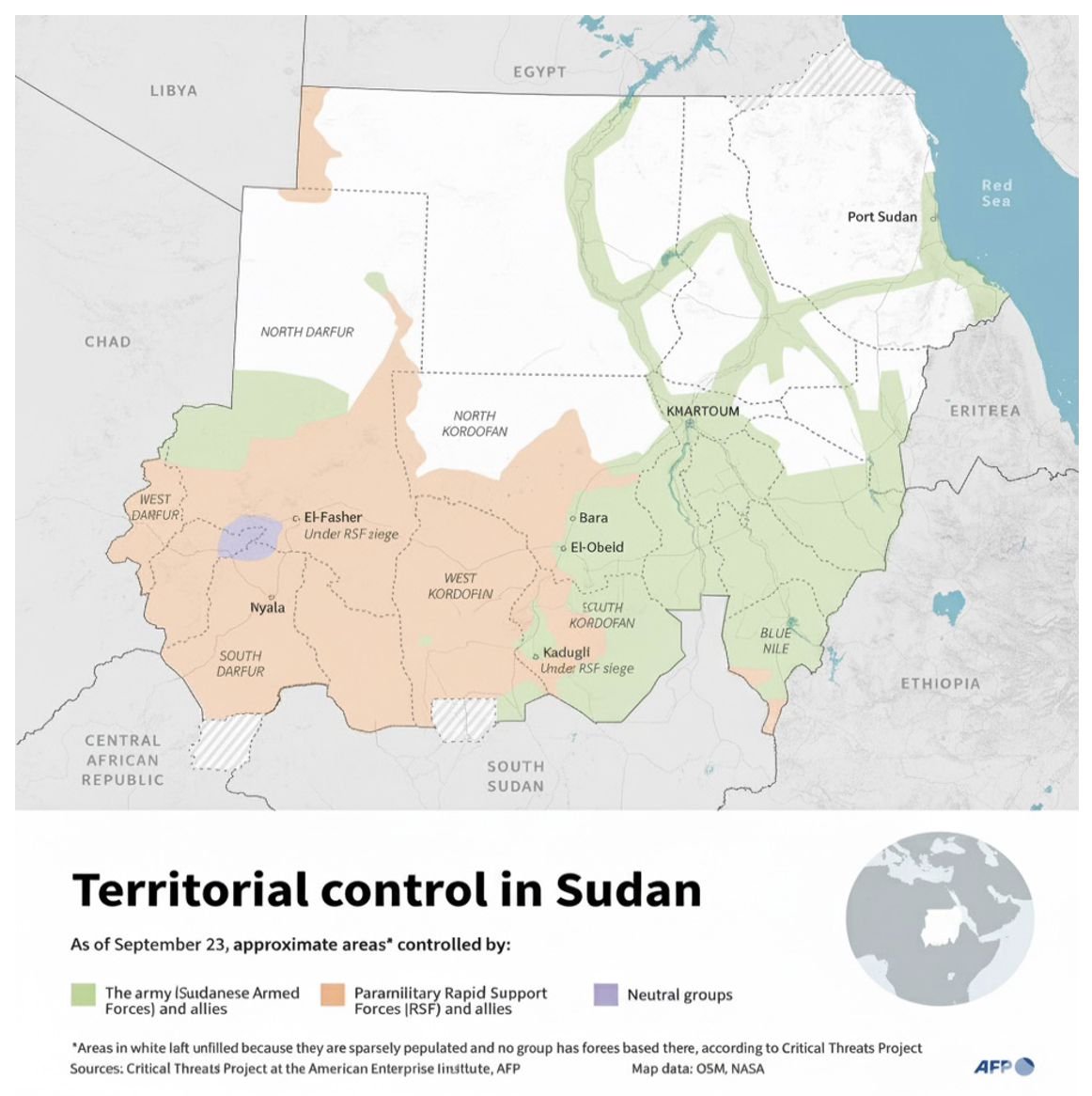

The conflict pits the regular army, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) of Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti. The SAF controls parts of the north and east of the country, including the strategic port of Port Sudan, while the RSF dominate Darfur and part of Kordofan. In this context of war, cultural heritage is increasingly exposed to looting and destruction. Museums, libraries, and historic sites have become targets for belligerents who see them more as an economic resource than as a legacy to be preserved.

Figure 1: Territorial Distribution of Forces in Sudan

Source : AFP

In Khartoum, the National Museum was occupied as early as June 2023 by the RSF. Its collections, tracing Sudanese history from the Paleolithic to the Christian kingdoms and the Nubian civilizations of Kerma, Napata, and Meroe, disappeared[1]. Through its unique collections and works of art, the museum represented an unparalleled testimony to the Nile Valley’s history. According to UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), other national museums suffered the same fate: the Ethnographic Museum, the Natural History Museum, and the Presidential Palace Museum were all ransacked[2].

In the provinces, the situation is no better. The Nyala Museum in South Darfur was devastated and converted into a military base. In El Fasher, the museum dedicated to Sultan Ali Dinar was destroyed in a fire caused by bombardments in January 2025[3]. The museums of El Geneina and Wad Madani were also affected. To these destructions must be added the loss of archives and documentary collections, making it even more difficult to reconstruct Sudan’s historical narrative.

These lootings fuel organized criminal networks. The Director of Museums at the Sudanese National Corporation for Antiquities, Ikhlas Abdellatif, has openly accused the RSF of smuggling antiquities westward, toward Sudan’s borders, particularly into South Sudan[4]. In November 2024, raids and arrests in the north of the country confirmed the existence of this trafficking: statuettes, pottery, and ancient weapons were seized at border crossings. Some museum pieces even resurfaced on online platforms such as eBay, fraudulently presented as “Egyptian antiquities”[5].

Figure 2: Online listing offering Sudanese artifacts for sale

Source: Sudan Tribune

Cultural heritage has thus become a commodity of war. According to several sources[6], the looting of Sudanese museums by the RSF forms part of a strategy to finance the conflict: objects are purchased by European and African art dealers, who then export them illicitly out of the country. This vicious cycle illustrates the intersection between the war economy and cultural heritage. For buyers, whether institutions or private individuals, these items have a commercial value, while for Sudanese communities they represent an identity and a memory.

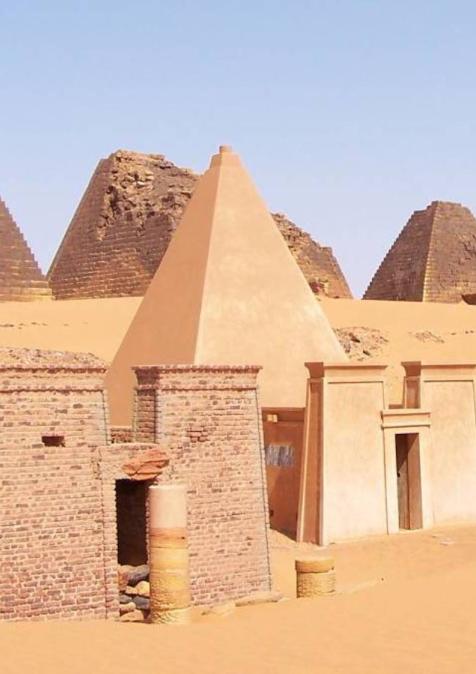

Some emblematic sites, such as the pyramids of Meroe or the sacred site of Gebel Barkal, have not been directly affected by fighting because of their geographical location, far from the main conflict zones of Khartoum, Kordofan, and Darfur. Yet this does not mean they are safe from destruction or looting. Neglect and lack of monitoring have led to their deterioration: erosion, graffiti, and uncontrolled climbing by visitors threaten their preservation. The sites of Naqa and Musawwarat es-Sufra, however, have suffered direct incursions by the RSF[7]. Such damage undermines monuments inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage, which are essential to world history.

Figure 3: Overview of Sudanese sites listed as UNESCO World Heritage

Source: author

Faced with these destructions, UNESCO reacted as early as 2023 by condemning the looting. The organization carried out the inventory and photographic documentation of more than 1,700 objects, trained police and customs officers to recognize stolen antiquities, and appealed to international museums and collectors to refuse illegal acquisitions[8]. Despite these efforts, the mobilization remains limited. Unlike the cases of Afghanistan or Iraq, Sudan has not benefited from strong media coverage denouncing the degradation and plundering of its cultural heritage. This lack of visibility has reduced international responsiveness.

Inside the country, civil society is attempting to save what can still be preserved. Experts from the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM) managed to secure and digitize collections, packaging and protecting more than 1,700 pieces across several regional museums[9]. Volunteers, archivists, and technicians have also played a role. Social media has become an important tool, with Facebook pages and X (formerly Twitter) accounts documenting losses and raising awareness.

International NGOs, such as Heritage for Peace, and professional organizations like ICOM (International Council of Museums), have also worked to prevent stolen artifacts from entering criminal networks. ICOM has issued warnings to its members about fraudulent purchases, while the ALIPH Foundation (International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas) has funded protective projects, such as paying museum guards and building flood protection systems. These initiatives demonstrate a solidarity that, while limited, remains crucial.

The degradation of cultural heritage undermines national identity and deprives future generations of historical landmarks. In a country already torn by ethnic, religious, and regional divisions, the absence of a shared heritage will make reconciliation more difficult. The destruction and looting of cultural heritage also threaten Sudan’s very ability to rebuild politically and socially.

The international community remains focused on the military and humanitarian dimensions of the conflict. Yet the protection of cultural heritage should be recognized as an essential aspect of resilience. The experiences of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria have shown that it is possible to mobilize resources to safeguard cultural heritage. If no action is taken in Sudan, the millennia-old legacy of the Nile Valley may be lost forever.

This situation underscores the urgency of both national and international mobilization to document losses, secure what can still be protected, and combat the illicit trafficking of the country’s museum treasures. Once peace is restored, Sudan’s reconstruction must include a cultural dimension, aimed at rehabilitating museums, restoring damaged monuments, and placing cultural heritage at the heart of national reconciliation.

[1] Au Soudan en guerre, les trésors des musées au cœur de pillages. 19 september 2024. https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1427780/au-soudan-en-guerre-les-tresors-des-musees-au-coeur-de-pillages.html

[2] UNESCO, COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE Soudan : l’UNESCO sonne l’alarme face aux menaces de trafic illicite de biens culturels, page 1.

[3] Sudan’s lost treasures: war fuels artefact trafficking. 22 january 2025. https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/sudans-lost-treasures-war-fuels-artefact-trafficking

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Sudan’s lost treasures: war fuels artefact trafficking. 22 january 2025. https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/sudans-lost-treasures-war-fuels-artefact-trafficking

[7] Au Soudan, les combats ont gagné des sites classés au patrimoine mondial. 17 january 2025. https://www.france24.com/fr/afrique/20240117-au-soudan-les-combats-ont-gagn%C3%A9-des-sites-class%C3%A9s-au-patrimoine-mondial

[8] Sudan: UNESCO steps up its actions as the conflict enters its third year. 16 april 2025. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/sudan-unesco-steps-its-actions-conflict-enters-its-third-year

[9] As Sudan’s civil war rages on, its heritage is under siege. 14 february 2024 https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2025/02/14/sudan-civil-war-rages-on-heritage-under-siege.