Publications /

Policy Brief

After 1994, everything was a priority, and our people were completely broken. But we made three fundamental choices that guide us to this day. One—we chose to stay together. Two—we chose to be accountable to ourselves. Three—we chose to think big.

— His Excellency President Paul Kagame, 20th Commemoration of the Genocide against the Tutsi (April 7, 2014)

Rwanda’s socio-economic progress since 1994 has been remarkable. Rwanda is rightly considered a showcase of the enduring power of visionary leadership. Despite remarkable achievements in sustaining high growth, improved well-being, and political stability, Rwanda remains a low-income country characterized by widespread poverty and vulnerability. Subsistence agriculture still prevails, and food security—though progress has been made—remains a distant goal for millions.

Today, Rwanda faces the challenge of climate change, which threatens to undermine its hard-won gains unless leadership builds on these achievements to transform agriculture and agri-food to be climate resilient, with sustainable, broad-based productivity and profitability. Such a transformation will not only require, but also drive, the transformation of the entire economy.

A tall order, no doubt, but nothing less will suffice to fulfill the leadership’s aspirations for Rwanda to become a middle-income country by 2035 and a high-income country by 2050. If visionary leadership and good governance prevail, Rwanda’s future will indeed be bright.

Introduction

Rwanda has risen from the ashes of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi.[1] Its reconstruction and recovery have been widely praised. The leadership’s zero tolerance for corruption has been a major asset in mobilizing substantial donor financing, particularly within the G20 Compact with Africa (CwA) (Sibindi, 2020).[2] Under visionary leadership committed to rebuilding “an ethnic-free Rwanda” (Lakin et al., 2014), the country has enjoyed domestic peace, national reconciliation, and sustained growth.[3] Since the 1990s, Rwandans have experienced a substantial increase in per capita income, as well as progress in multiple dimensions of human development and poverty reduction (World Bank Group, June 2019).

While still a low-income country—USD 1,040 (2024, Atlas method, WDI)[4]—it aspires to become a middle-income country by 2035 and a high-income country by 2050 (World Bank, Overview, April 2025). These high ambitions imply double-digit annual per capita growth, that is over 10% per year. To achieve these high growth rates, Rwanda must continue to transform its economy. It has been pursuing sectoral strategies under its National Strategy of Transformation (NST).[5]

This policy brief addresses the following main question: On what do Rwanda’s prospects for achieving an inclusive, climate-resilient, high-growth and food-secure future depend? To answer this question, Section I presents a brief overview of salient features of Rwanda’s development experience since the return to peace, focusing on key areas of structural progress or lack thereof. Section II discusses its achievements in poverty reduction and the progress still needed. Section III reviews the role and contribution of the agriculture and agri-food sector to the overall economy and key constraints that must be addressed for it to become a major engine of transformational growth under climate change. Section IV considers options available to Rwanda to address the twin challenges of climate change and its youth bulge. Ultimately, Rwanda’s prospects for achieving food security within a generation will largely depend on how national leadership responds to these defining challenges.

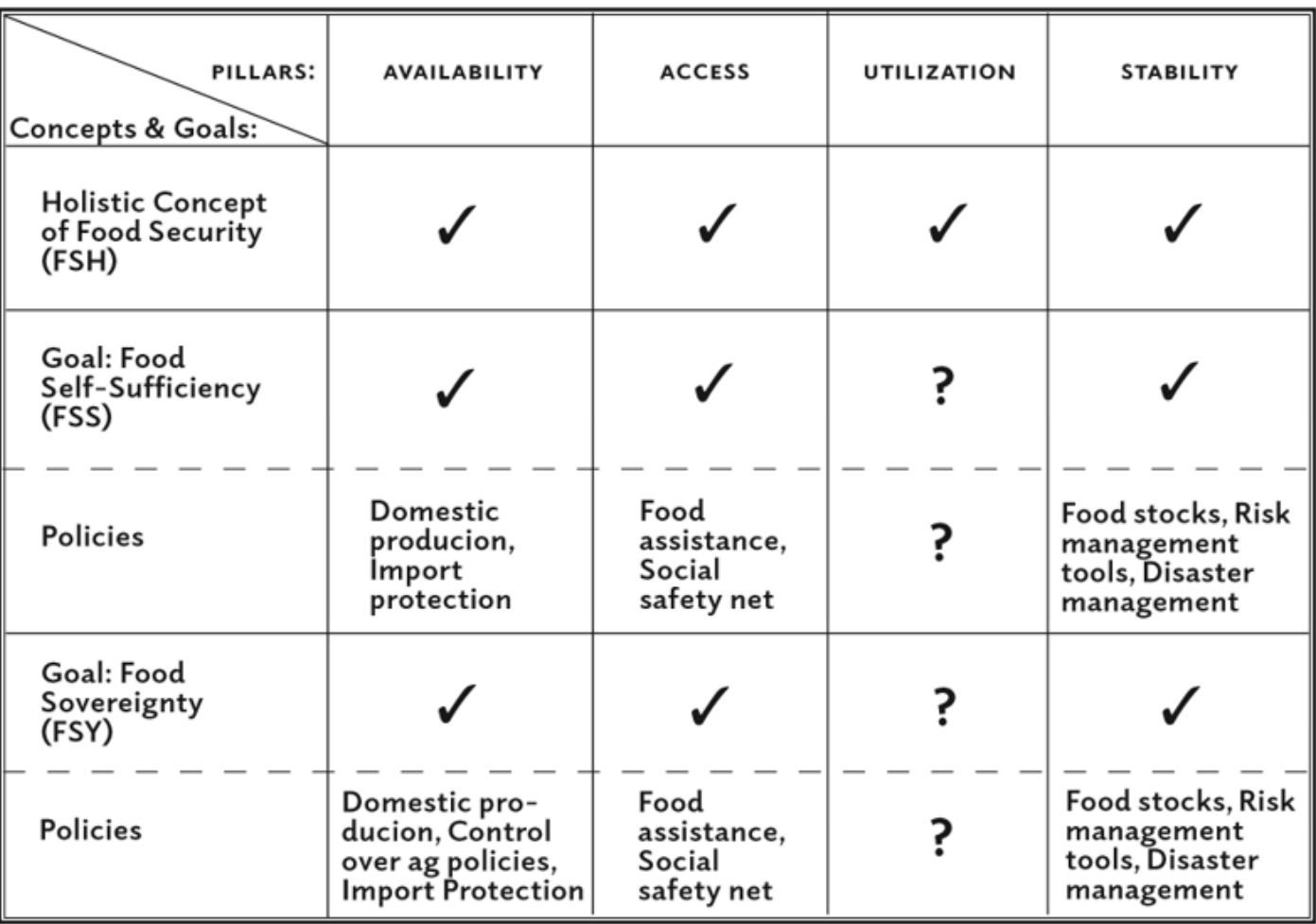

Rwanda has adopted a food self-sufficiency (FSS) approach to agriculture and agri-food development. It is therefore important, at the outset, to distinguish it from two other important concepts: food sovereignty (FSY) and the holistic FAO food security (FSH) concept. FSS refers to a country’s ability to depend solely on its domestic production to satisfy its people’s consumption requirements (typically of basic staples). Food sovereignty, first articulated by La Via Campesina (1996) and in the Declaration of Nyeléni (2007), states:

“Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

While the food self-sufficiency concept prioritizes a country’s ability not to depend on food imports, the food sovereignty concept stresses the ability of local food producers to determine their own food systems, and not to depend on foreign markets and multi-national corporations.

Food security (FSH), as defined by the FAO, differs in that it does not inherently favor nationalism or trade protection. It is achieved when the four pillars—availability, access, utilization and stability—are simultaneously realized.

For all three concepts, it is a matter of degree to which each is realized. Distinguishing among them is crucial, as each carries different but profound implications for resource allocation and development policy. (See Annex 1 for a graphical presentation of the three concepts of food security.)

Section I: Overview of Key Features of Rwanda’s Developmental Experience since 1994

Major achievements since the end of the genocide: After a transitional period under the Government of National Unity in the 1990s, the Rwanda Patriotic Front-dominated governments (GORs) have espoused clear principles of governance anchored in a strong centralized and capable state; zero tolerance for corruption;[6] commitment to a market economy with a strong private sector; gender equality; environmental sustainability; and science and technology.

By effectively controlling corruption, Rwanda became a favored recipient of development assistance: Rwanda ranked in the 71st percentile according to World Governance Indicators (WGI)[7]—a favorable rating not only ahead of the average for low- and middle-income countries but also higher than that of many upper-middle-income countries (World Bank Group, October 2020). Rwanda’s success in mobilizing external finance has, in turn, contributed to its ability to raise its public investment from 5% of GDP to an average of 15%.[8] Together with foreign direct investment (FDI) and borrowing, this has fueled high growth: since the early 2000s, per capita GDP growth has averaged 5% per year, second in Africa only to Ethiopia.

Public investment has focused on conventional infrastructure including roads and energy, as well as on modern infrastructure aimed at positioning Rwanda as a major center for business, financial, and communication services. Investments have targeted air services, convention and tourism facilities, and the modernization of urban Kigali. Distinctive projects include MICE facilities (Meetings, International Conferences, and Events).[9]

Selected features of economic performance pre- and post-Covid-19: Before Covid-19, Rwanda’s economic growth averaged 9-10%, largely driven by high public investment. Total Factor productivity (TFP) growth was a major source of growth during 2001-2011. Construction, mining, trade, and transport have each grown at 9-10% annually since 2006, while manufacturing expanded at 7% and agriculture at 5.5%. New sectors such as eco-tourism, business tourism, and food processing also emerged as important contributors to growth.

The onslaught of Covid-19 dealt a severe blow: the government was forced to impose a lockdown of the economy and support families through the Social Protection and Recovery Plan (May 2020-December 2021). At the same time, sub-sectors such as trade, manufacturing, hotels, and restaurants experienced considerable declines in sales. As a result, growth fell sharply, with GDP estimated to decline to 2% in 2020 (World Bank Group, October 2020).

Nevertheless, Rwanda’s business climate continued to improve, as reflected in its 2020 Doing Business rankings. Economic recovery has been strong, with GDP growth reaching 8.2% in 2023 and 8.5% in 2024.

Despite these positive trends, several concerning signs remain:

High levels of public debt, projected to peak at 80% of GDP in 2025.

A slowing down of poverty reduction between 2011 and 2017.

Sluggish TFP growth in recent years (2012-2016), especially in agriculture.

Persistently high unemployment, with the overall rate at 12% (2024) and youth (15-24) unemployment at 17.5% (WDI).[10]

Section II: Extent and Incidence of Poverty, Vulnerability and Inequality since 2000

Poverty extensive despite major improvements: Between 2001 and 2017, extreme poverty (USD 1.9/day) fell from approximately 77% to 56%. Using the national poverty line, reduction declined from around 60% to 38%. However, progress stagnated between 2014 and 2017 due to extreme weather events,[11] a slowdown in structural transformation,[12] and slower rural-to-urban migration.

More than 90% of the poor live in rural areas, especially in the southern, western and eastern provinces. Female-headed households are more vulnerable than male-headed households: around 40% of female-headed households were poor versus 38% of male-headed households. Female-headed households also engaged in independent farming at higher rates than male-headed households (62% versus 43%).

Inequality has decreased: the Gini coefficient fell from 0.51 (2001) to 0.45 (2014) and 0.43 (2017) (World Bank Group, 2019). Fertility and dependency ratios have declined. Infant mortality decreased from 44.5 deaths/1000 births (2010) to 28.9 deaths/1000 births (2017); under-five mortality fell from 51.5/1000 to 39.1/1000. Maternal health and child nutrition have improved, although the target to reduce child stunting (age five and under) from 38% (2015) to 19% by 2024 has not yet been reached.[13]

Significant improvements have also been made in access to water sources, sanitation, electricity, and housing conditions between 2011 and 2017. Women’s empowerment has been a key priority of leadership.

Women now hold more than 50% of cabinet positions.

Primary school enrollment and completion rates are equal for boys and girls.

Laws against gender-based-violence (GBV) have been enacted.

Institutional reforms, including land reform, have strengthened women’s control over domestic property, contributing to overall growth and poverty reduction.[14]

Despite significant progress, poverty in Rwanda continues to exhibit troubling features: At the extreme poverty level (USD 1.9/day), Rwanda’s poverty incidence remains much higher than that of neighboring peers with similar GNI per capita (in PPP terms), such as Mali and Chad. Moreover, the growth elasticity of poverty reduction (at the USD 1.9/day level) in Rwanda between 2001 and 2017 is lower than that of Senegal (2001-2011), Burkina Faso (1998-2014), and Uganda (1998-2016).

Rwanda’s human capital prospects are similarly sobering.[15] According to the World Bank’s Human Capital Index (HCI), children born today are expected to be only 37% as productive as they would be if they had access to complete education and full health (World Bank Group, October 2020).[16]

Section III: Agriculture and Agri-food[17] under the Threat of Climate Change

Key features of agriculture and agriculture policy in the 2000s: Rwanda is a small,[18] landlocked country, known as the “Land of a Thousand Hills”. Its hilly topography means that much of its agriculture is practiced on terraces. Although located just two degrees south of the Equator, its high elevation gives it a relatively mild highland climate with distinct wet and dry seasons.

Rwanda’s economy remains heavily agriculture-based: the sector accounts for approximately 28% of GDP, 50% of total employment (2020s), and around 50% of goods exports.[19] Farm sizes are small, roughly 0.6 ha per farm or roughly 0.12 ha per worker.

Unlike many African countries, Rwanda has consistently allocated around 10% of total government budget to agriculture, as recommended by the Malabo Declaration (2014), a clear indication of the key importance accorded to the sector by GOR. Significant institutional changes have shaped the sector:

Land consolidation through the Land Use Consolidation Program (LUCP) in 2007.

Crop Intensification Program (CIP) in 2008, facilitated by land consolidation.

Irrigation development on marshlands and hillsides, and terracing between 2008 and 2012.

Land reform and registration (2009-13), issuing secure titles to individual farmers—especially women—covering 10.7 million parcels of agricultural land, or roughly 90% of all land.

In line with tradition, all marshlands belong to the Rwandan state. However, the RPF government formalized this under Article 29 of the Organic Land Law (July 2005). Marshlands occupy around 10% of Rwandan territory (Ansoms, 2013).

Cooperative development along commodity lines corresponding to value chains, e.g., rice, maize, potatoes, beans, coffee, tea, horticulture, and dairy (WBG and Government of Rwanda, 2020).

These institutional changes made a major contribution to TFP growth of around 2% per year. The National Agricultural Policy (2004) and its four- to five-year implementation plans emphasized the growth of staple food crops, in line with Rwanda’s FSS approach—an emphasis reinforced by the 2008 food crisis. Since the early 2000s, agricultural growth has averaged 5% per year, driven mainly by land expansion, increased labor input and greater use of inputs.

However, subsistence agriculture remains predominant, making agriculture the sector with the lowest productivity, with TFP growth slowing in recent years (since around 2011). Agricultural development of the swamplands under top-down state direction has also raised concerns: it has been associated with lower productivity, limited employment creation,[20] and reduced function as a local safety net (a risk-coping mechanism against famine) to local populations. For example, monocropping on swamplands has produced such negative outcomes—as seen in the concession granted to the Madvani Business Group, which cultivated sugar only (Ansoms, 2013).

The pace of structural transformation[21] has also slowed. Non-farm employment rose from 4% to 10% between 2001 and 2011, but the absolute numbers of workers in agriculture has continued to increase since 2011 (World Bank Group, 2019). For the economy as a whole, both labor productivity and TFP remain low relative to Rwanda’s income level (World Bank Group and Government of Rwanda, 2020).

The strengths and weaknesses of Rwanda’s food self-sufficiency approach to agricultural development in an environment of climate change: The GOR has focused on promoting staples while implementing the above structural changes. Specifically, the GOR decided which staple varieties to plant, when, and with what inputs. It distributed subsidized fertilizer and improved seed inputs for wheat and maize through cooperatives. While agriculture has grown under this interventionist FSS policy approach, the growth has primarily been through land expansion and increased inputs. Hence, there are clear risks in maintaining this approach, as TFP is slowing down and the scope for further land expansion is extremely limited. Continued high population growth will further increase this already tight land constraint.

For the high-income growth targets of the current RPF leadership to materialize, agriculture value added per worker must increase more than eight-fold by 2035, and then more than triple again by 2050 to reach levels comparable to high-income countries (World Bank Group, Sept 2022). These increases are impossible to achieve under the current FSS approach.

Another key factor that can undermine such high growth is climate change. Rwanda is extremely vulnerable to climate shocks, as (i) recent extreme weather events have shown; [22] (ii) agriculture and food, as well as eco-tourism, are climate-sensitive; and (iii) poverty and hunger remain extensive. Moreover, there has been a steady decline in forest cover since 1990 as cropland has expanded.[23] This decline in forest cover[24] inevitably increases Rwanda’s vulnerability to climate change.

Mean annual temperature in Rwanda has already increased by 1.4o C in the southwest and 2.6o C in the east between 1971 and 2016. Serious droughts in the eastern regions have alternated with excessive rainfall. The rainy seasons have become shorter and more intense in the northern and western provinces, leading to increased erosion in mountainous areas and greater risks of floods, landslides, and soil/environmental degradation. Relative to 1970, precipitation is expected to rise by 5-10% by the 2030s. With increased variability in precipitation, crop yields and agricultural production are projected to become more volatile. Temperature rises may also reduce the yields of important crops such as plantains, cassava, potatoes, sweet potatoes, maize, and beans (Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Environment, 2017).

Section IV: What prospects lie ahead for a food secure Rwanda? Challenges and opportunities

Two mega trends—climate change and the youth bulge—challenge the current FSS approach to agricultural and economy-wide transformation: Together, they present an existential challenge to Rwanda’s developmental ambitions.

Climate change: The frequency and severity of weather events (e.g., droughts, floods, and rising temperatures) are expected to persist under climate change, inflicting a heavy toll in terms of disruptions, loss of lives, and output. According to the latest ND-GAIN[25] Index (2023), Rwanda ranked 114 out of 187 countries evaluated with a score of 43.6.[26] This indicates that Rwanda is not only highly vulnerable to climate change (e.g., extensive floods triggering landslides),[27] but also inadequately equipped to be resilient. Rising temperatures are projected to reduce labor productivity both directly and indirectly (through deteriorating health). Furthermore, under a scenario of a 1.5oC increase in temperature, tourism—an especially climate-sensitive sector—could decline by 11%. If temperatures rise by 2oC between 2040 and 2059, tourism could fall by as much as 20% (World Bank Group, September 2022).

Youth bulge: Rwanda is a youthful nation, with a median age of 19.9 years. Youth (ages 16-30) accounts for 27% of the total population, with the 16-20 age group forming the single largest group. With population growth at 2.14 % per year,[28] GOR faces sustained pressure to create job-generating growth for decades to come. During 2001-2011, Rwanda’s non-farm economy successfully absorbed 84% of new labor force entrants; however, during 2011-2017, absorption capacity fell to only 50% (World Bank Group, 2019), reflecting a slowdown in structural transformation. In addition, high investment in sectors identified by GOR as strategic, e.g., those providing high-value services such as MICE facilities, including luxury hotels, convention infrastructure, and air transport (RwandAir), are capital-intensive. Economy-wide spillovers from such large capital investments have yet to fully materialize. In any case, they were always conceived as long-term investments and substantial short-term returns were not expected. The youth employment challenge is further exacerbated by Rwanda’s low level of human capital accumulation. More than 70% of adults in the bottom 40% of the income distribution (B40) have either no schooling at all or only incomplete primary schooling, leaving a large share of young people unprepared to compete for knowledge-based jobs in high-value service sectors.

What opportunities hold promise to effectively address these twin challenges? The global community is witnessing a fast retreat from globalization as geo-political tensions mount, especially among major world powers. Protectionism (also called nearshoring or friendshoring) is fragmenting and reshaping global trade. However, African governments have a historic opportunity to leverage the transformative power of intra-African trade among 54 friendly nations under the AfCFTA, reaching 1.4 billion people with a combined GDP of roughly $3 trillion. For example, under full implementation, the Africa Common External Tariff-East African Community (CET-EAC) scenario projects that the agri-food sector would see intra-African trade increase by 5.32% while the industry sector would record 1.21% growth (ECA & AU, 2025).

For a small land-locked country like Rwanda, expanding trade at both Africa-wide and global levels offers a promising way to overcome the constraints of its small domestic market and the limits of its FSS approach. In other words, Rwanda needs to tap into scale economies and specialization by integrating into regional and global value chains made possible by access to expanding markets. To contribute to Rwanda’s developmental aspirations for the next generation, agriculture and agri-food, including agro-based processing, must generate broad-based, sustainable productivity growth that is resilient to climate change. In the immediate and short term, Rwanda should continue to exploit the opportunities offered by Regional Economic Communities (RECs) such as the EAC and COMESA, while at the same time developing and strengthening the institutional measures required to fully integrate its economy within the AfCFTA.[29]

Promising options to exploit trading opportunities: For agriculture and agri-food to serve as an engine of climate-resilient and inclusive growth, GOR must expand irrigation opportunities and marketing channels for high-value outputs such as crops, horticulture, floriculture, livestock, and processed foods. Currently, agriculture remains largely rainfed, with less than 5% of all cultivated land irrigated—just 7.5% of its irrigable potential. Only 16% of potential irrigable marshlands has been developed (World Bank Group and Government of Rwanda, 2020).

Because irrigation development is costly,[30] irrigated produce must be directed toward high-value crops (e.g., horticulture, dairy) for domestic, regional, and global markets. An impact analysis of irrigated horticulture indicates that annual household income could rise by 20%, while profits increase by an estimated 16% of annual income per median landholding. Subsistence farmers living near irrigation schemes also benefit through improved employment opportunities (World Bank Group, June 2019).

Policy tradeoffs and synergisms must, however, be carefully considered. For instance, promoting irrigation could reduce the water available for energy generation, particularly hydropower (Johnson et al., 2019). Yet hydropower remains a crucial factor in Rwanda’s goal of decarbonizing its entire economy.[31]

No less than a multi-sectoral policy, institutional reform, and investment agenda is required: Successfully unlocking Africa-wide regional trading opportunities in agriculture and agri-food could transform a subsistence-based, low-productivity, rain-fed agricultural system into a high-performing sector—inclusive, climate-resilient, and well-integrated into regional and global economies. This agenda would include: (i) strengthened agricultural research, extension and training services to develop and disseminate climate-smart agriculture;[32] (ii) soil,[33] landscape, and water[34] management programs; and (iii) key investments to address cross-cutting inadequacies. Priorities in the latter include:

Transport, storage, and communications infrastructure: Good quality infrastructure is essential for any economy that aspires to be well integrated into expanding and thriving markets. For Rwanda, which remains primarily rural, rural roads are particularly critical. Yet more than half of the rural population lack access to a network of roads that are in good condition within a 2-km walking distance. Beyond expanding quality roads, road safety has also emerged as a key issue, especially for youth. Farmers likewise face shortages of reliable post-harvest storage facilities and cold-chain systems for highly perishable produce.

Health and human capital: Human capital—encompassing health, education, and skills—is a key factor shaping employability and labor productivity, including in agriculture.[35] Rwanda has already invested heavily in urban infrastructure to support high-value service sectors. It now needs to complement this by investing in youth who are eager and capable of driving these services. A healthy, educated, and skilled labor force will also enable Rwanda to harness the opportunities of the current industrial revolution 4.0 (e.g., robotics, the Internet of Things, three-dimensional printing, AI). Human capital investment is therefore particularly urgent in improving the quality of education, ensuring smooth transitions from primary to secondary, and from secondary to tertiary, including vocational, technical and language training. In health, strengthening basic services such as water and sanitation remains critical.

Social protection for the poor and vulnerable, including strengthened rights and opportunities for girls and women: Because the broader reforms will take time to bear fruit, it is essential to support the weaker members of society so they too can contribute to and benefit from a higher-income, food-secure, and climate-resilient Rwanda.

Already on its long march, Rwanda is committing itself to mobilizing the financing required for economy-wide transformation: GOR has begun implementing some of the above measures through the four- to five-year tranches of its Strategic Plan for Agriculture Transformation, which aims to transform agriculture by 2050. Under Vision 2050, GOR seeks to make agriculture 15 times more productive than it is today. This transformation is seen as a cornerstone of the broader national transition toward a carbon-free, climate-resilient economy. The financing challenge is steep—estimated at the equivalent of 8.8% of GDP every year until 2030—an amount that far exceeds recorded and projected financial flows from ODA and FDI for the period 2015-2030[36] (World Bank Group, September 2022). Yet as costly as this transformation will be, can a low-income, agriculture-based economy afford the far greater costs of ignoring climate change?

Conclusion: So, what are the prospects?

This is, of course, a question for the government and the people of Rwanda to answer. Yet, given their post-genocide history, is there any doubt about what the answer will be?

After the Genocide (1994), Rwanda dared to “…think big”. Leadership took on the daunting challenge of rebuilding a nation shattered by ethnic hatred. The Kigali Genocide Memorial stands as both “a warning and a symbol of hope…” (Ban Ki-Moon, UN Secretary-General, 2007-2016). Rwanda’s post-genocide developmental achievements are also a source of hope, demonstrating that visionary leadership can mobilize the financial, human, and institutional resources needed—even against formidable odds.

If history is any guide, Rwandan leadership and its people will continue to “…think big.” Successfully confronting the existential challenge of climate change demands nothing less.

Annex 1

Diagram 1: Food Security: Main Concepts, Pillars, Goals and Policies

Bibliography

Ansoms, An. March2008. “Striving for Growth, Bypassing the Poor?” A Critical Review of Rwanda's Rural Sector Policies. Source: The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 1-32 Published by: Cambridge University Press. https://jstor.policycenterforthenewsouth.ma/stable/pdf/30224872.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A6c8800f7661110ab63d2d000951350c7&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=search-results&acceptTC=1

Ansoms, An. 2023. “Large-Scale Land Deals and Local Livelihoods in Rwanda: The Bitter Fruit of a New Agrarian Model” Source: African Studies Review, Dec. 2013, Vol. 56, No. 3 pp. 1-23. https://jstor.policycenterforthenewsouth.ma/stable/pdf/43905052.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A8a00f7ecdf7de73c6ff27d432b19f50e&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=search-results&acceptTC=1

Ansoms, An and Donatella Rostagno. September 2012. “Rwanda's Vision 2020 halfway through: what the eye does not see” Source: Review of African Political Economy, September 2012, Vol. 39, No. 133, pp. 427-450. https://jstor.policycenterforthenewsouth.ma/stable/pdf/42003222.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A6c8800f7661110ab63d2d000951350c7&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=search-results&acceptTC=1

Economic Commission for Africa (ECA)& African Union (AU). 2025. DELIVERING ON THE AFRICAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY: Towards an African Continental Customs Union and African Continental Common Market. https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/fullpublicationfiles/ARIA%20XI_Book_EN_12June_rev1.pdf

Johnson, Oliver W.,Cassilde Muhoza, MbeoOgeya, Tom Ogol, Taylor Binnington, Francisco Flores and Louise Karlberg. Nov 2018. “Policy coherence around energy transition and agricultural transformation in Rwanda.” Stockholm Environment Institute. https://jstor.policycenterforthenewsouth.ma/stable/pdf/resrep22992.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A8a00f7ecdf7de73c6ff27d432b19f50e&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=search-results&acceptTC=1

Kaufmann, Daniel and Aart Kraay. Nov. 2024. The Worldwide Development Indicators: Methodology and 2024 Update. Policy Research Working Paper, # 10952. World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099005210162424110/pdf/IDU-7c6f0b9e-f0c2-4b1d-b30d-76c4644af69e.pdf

Lakin, Samantha and Jonathan Beloff. 2014. “Leadership Mindsets”. Source: Journal of African Union Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2/3, Political Leadership in Africa: Renaissance or Regression? pp. 47-67, Jo-AnsieVan Wyk. Published by: Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd. https://jstor.policycenterforthenewsouth.ma/stable/pdf/26893864.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A8a00f7ecdf7de73c6ff27d432b19f50e&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=search-results&acceptTC=1

Notre Dame-Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). 2023. https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/rankings/

Sibindi, Ntandoyenkosi.2020. “G20 Compact with Africa: Consolidating and Accelerating Rwanda’s Transformation Agenda .“https://jstor.policycenterforthenewsouth.ma/stable/pdf/resrep25955.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A8a00f7ecdf7de73c6ff27d432b19f50e&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=search-results&acceptTC=1. South African Institute of International Affairs.

Verhofstadt, Ellen and Miet Maertens. March 2015. “Can Agricultural Cooperatives Reduce Poverty? Heterogeneous Impact of Cooperative Membership on Farmers' Welfare in Rwanda.” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 86-106 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association. https://jstor.policycenterforthenewsouth.ma/stable/pdf/43695856.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A29a303a25ee178c80c0cf694e812bd87&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&initiator=search-results&acceptTC=1

World Bank Group (WBG). June 25, 2019. Rwanda: Systematic Country Diagnostic. Report No. 138100-RW. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/219651563298568286/pdf/Rwanda-Systematic-Country-Diagnostic.pdf

World Bank Group (WBG). Oct. 2020. Rwanda Country Partnership Framework, FY 21-26. Report No. 148876-RW. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/645111594605654868/pdf/Rwanda-Country-Partnership-Framework-for-the-Period-of-FY21-FY26.pdf

World Bank Group and the Government of Rwanda. 2020. Future Drivers of Growth in Rwanda: Innovation, Integration, Agglomeration and Competition.file:///Users/isabelletsakok/Downloads/9781464812804.pdf

World Bank Group (WBG). Sept 2022. Rwanda: Country Climate and Development Report.https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099645309262220643/pdf/P1769550c7dc4c0d0085ee0617377dc7cd6.pdf

World Development Indicators (WDI) Rwanda 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD

World Development Indicators (WDI). Unemployment, youth total (% of labor force ages 15-24) (modeled ILO estimate) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS

World Bank Group. “Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA)” Updated Feb 2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climate-smart-agriculture#:~:text=Climate%2Dsmart%20agriculture%20(CSA),ensure%20food%20security%20for%20all.

World Bank. April 04, 2025. Rwanda: Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/rwanda/overview

[1] The 100 days in 1994—from April to July—were marked by pure terror, as Hutus massacred Tutsis, moderate Hutus, and Twas, claiming the lives of possibly one million people, though the exact toll is still debated. The genodice was triggered by the shooting down of President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane on April 06, 1994. In the aftermath, Rwanda became the world’s second-poorest economy, with only Mozambique considered poorer. Its GDP per capita was estimated at around USD 228 in 1995.

[2] The Compact with Africa (CwA) initiative was launched in 2017, during Germany’s G20 presidency, with the agenda to “foster sustainable and inclusive growth and development.” The African Advisory Group, co-chaired by South Africa and Germany, oversees the CwA, while coordination is provided by the African Development Bank (ADB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank (WB) (Sibindi, 2020).

[3] A core ideological credo of the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) is a “Single Rwanda”, a vision of “unified people.” In 2008, Rwanda passed the Genocide Ideology Law, an anti-discrimination law aimed at combating genocide ideology.

[4] The World Bank classifies countries into four income groups—low, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high—based on Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. For the 2026 fiscal year (based on 2024 data), these are defined as follows: Low-income: GNI per capita of $1,135 or less; Lower-middle-income: GNI per capita between $1,136 and $4,465; Upper-middle-income: GNI per capita between $4,466 and $13,845; High-income: GNI per capita greater than $13,846.These classifications are used for analytical purposes and are updated annually on July 1, using the previous calendar year's GNI per capita data.

[5] The National Strategy for Transformation (NST, 2014-2024) is a medium-term strategy to build progress to achieving Vision 2050.

[6] Critics, however, make a distinction between technocratic governance for which Rwanda is praised, and political governance, which refers to voice and accountability, political and civic liberties, where Rwanda is rated poorly. With respect to political governance, Rwanda ranks among the bottom 10% of countries (Ansoms et al., September 2012).

[7] The sources, construction, and interpretation of World Governance Indicators (WGI) is discussed in Kaufmann and Kraay, November 2024. WGIs are built on six aggregate governance indicators: (1) Voice and Accountability; (2) Political Stability and the Absence of Violence/Terrorism; (3) Government Effectiveness; (4) Regulatory Quality; (5) Rule of Law; and (6) Control of Corruption, covering a sample of 214 economies over the period 1996-2003.

[8] Flows of ODA for Rwanda have averaged 17% GDP annually, nearly 5% more than the average for SSA-IDA countries (World Bank Group, October 2020).

[9] Facilities of note include the Kigali Convention Center, RwandAir (the national airline), the Bugesera Airport (completion expected by 2028), several high-end, 5-star hotels, and a modern sports arena.

[10] Rwanda, with a population of around 14 million in 2024, is a youthful country. Population density is estimated at 578 persons per sq. km (1,497 per sq. mi). Among low-income countries, Bangladesh has the highest population density, at 1,333 persons per sq. km (2024).

[11] Rwanda experienced a drought in 2016, which was followed by extensive floods and landslides in 2018 and 2019.

[12] Structural transformation towards a higher-income economy occurs when labor moves from low–productivity, such as subsistence agriculture, to higher-productivity non-farm sectors.

[13] Stunting is a major problem for the poorest households: nearly 50% of children from the two poorest wealth quintiles are stunted, compared with 20% among the richest (World Bank Group, October 2020).

[14] Regarding cooperative development, critics note that cooperatives tend to exclude poorer and more remote households. While they benefit members through higher production and income, they can also be exclusive (Verhofstadt et al., 2015).

[15] Productivity-linked indicators included in the Human Capital Index (HCI) are: (i) probability of survival to age five; (ii) expected years of schooling; (iii) harmonized test scores as a measure of the quality of learning; (iv) the adult survival rate; and (v) proportion of children not stunted.

[16] The 2018 Human Capital Index (HCI) covered 157 countries.

[17] The term “agriculture” also includes agri-food and agri-processing. In this policy brief, the term “agriculture” will be used throughout. The context will indicate whether it refers to primary production, processing, or both.

[18] Rwanda is roughly the size of the State of Maryland in the United States, covering an area of 10,169 sq. km or 26,338 sq. mi. Its altitude ranges from 950 m to 4,507 m above sea level.

[19] In 2000, agriculture contributed to about 45% of GDP and 90% of the active working population (Ansoms, March 2008).

[20] The jobs were criticized as being badly paid and insecure (Ansoms et al., September 2012).

[21] Structural transformation of an economy refers to a fundamental shift in economic structure as labor moves from lower productivity agriculture to higher productivity non agriculture, namely industry and services sectors. When this process slows down, surplus agricultural labor remains “stuck” in lower productivity agriculture. Rwanda cannot achieve its middle- and high-income status without sustained and vigorous continual structural transformation.

[22] For example, drought in 2016 and extensive flooding and landslides in 2018 and 2019. The 2016 drought impacted 12% of the population (World Bank Group, September 2022).

[23] Some 90 % of cropland is on slopes, hence more vulnerable to landslides.

[24] A major reason for deforestation and land degradation is the demand for biomass for energy use.

[25] ND-GAIN stands for: Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative. The ND-GAIN country index summarizes the country’s vulnerability to climate change and other global challenges in combination with its readiness to improve resilience (See ND-GAIN, scores for 2023).

[26] For comparison, the top rank and score for 2023 was held by Norway: rank 1, score 76.8. The ideal status is 0, indicating least vulnerable, and 1, indicating most readiness to meet the climate change challenge.

[27] In 2015, it was estimated that 45% of paved roads, 39% of unpaved roads, and 74% of district roads, were exposed to landslides. More generally, Rwanda’s road network is unprepared to withstand severe weather events (World Bank Group, September 2022).

[28] Rwanda’s fertility rate is high but declining. The infant mortality rate is also declining.

[29] These requirements are wide-ranging investments, including infrastructure projects under the Program for infrastructure development in Africa (PIDA), and institutions for the CET (customs union) and COM (continental common market) among others (ECA & AU, 2025).

[30] The cost of irrigation is $ 6000-8000 per hectare in the marshlands, three to four times higher than on the hillsides (World Bank Group and the Government of Rwanda, 2020).

[31] Rwanda’s 2020 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) sets out the investments needed in agriculture, forestry, urbanization, public health and infrastructure to enable Rwanda to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

[32] Climate smart agriculture is not one single set of agricultural practices. Instead, it is context-specific and can embrace a variety of sustainable and climate-resilient practices such as conservation tillage, cover cropping, soil and nutrient management, water management, livestock management, and agro-forestry. “Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) is an integrated approach to managing landscapes—cropland, livestock, forests and fisheries—that address inter-linked challenges of food security and climate change” (World Bank Group, February 2024).

[33] Due to increased population density, there has been a reduction in vegetation and increased run-off, resulting in soil loss.

[34] A steady depletion of Rwanda’s forest and water resources has made Rwanda more vulnerable to climate change.

[35] Smart agriculture is a form of precision agriculture that requires a literate and skilled farming community.

[36] ODA: Overseas Development Assistance. FDI: Foreign Direct Investment.