Publications /

Policy Brief

Morocco’s strong macroeconomic performance over the past two decades—anchored in infrastructure modernization, industrial diversification, and renewable energy leadership—has positioned it as a success story in the Global South. Yet these achievements mask persistent regional disparities that undermine inclusive development. Coastal regions such as Casablanca-Settat and Tangier-Tétouan-Al Hoceima dominate economic activity, while hinterland and southern provinces face structural disadvantages in employment, connectivity, and public services. Drawing on the Williamson hypothesis of an inverted U-shaped relationship between growth and inequality, this policy brief situates Morocco on the upward slope of rising regional disparities. It examines the historical roots of spatial imbalance, the limits of decentralization, and the structural concentration of growth in metropolitan hubs. While recent reforms, including the New Development Model (2021) and the Investment Charter (2022), aim to foster territorial equity, sustained progress will require a shift toward territorially sensitive policies that empower regions to drive more balanced and inclusive national development.

Introduction

Economic growth is often regarded as the engine of development—expected to lift living standards, reduce poverty, and create opportunities. Yet when its fruits are unevenly distributed across space, growth can become a double-edged sword. In many developing countries, rapid economic expansion has exacerbated existing geographic inequalities, concentrating wealth and infrastructure in a few privileged regions while leaving others behind. Such spatial disequilibrium undermines the inclusiveness of growth and poses risks to national cohesion, social stability, and long-term sustainability.

Morocco exemplifies this challenge of territorially unbalanced development. Over the past two decades, it has emerged as a success story in terms of macroeconomic performance, infrastructure modernization, and sectoral diversification. From high-speed railways and world-class ports to renewable energy leadership and industrial integration, the country has pursued ambitious development strategies. However, these achievements coexist with persistent—and in some cases widening—regional disparities. Coastal regions such as Casablanca-Settat, Rabat-Salé-Kénitra, and Tangier-Tétouan-Al Hoceima have consolidated their dominance in economic output, infrastructure, and access to services, while hinterland and southern provinces continue to lag in employment, public service provision, and productive investment.

Understanding the roots of this uneven trajectory requires looking beyond recent economic trends to Morocco’s historical development path and regional policy evolution. Since independence in 1956, Morocco has transitioned slowly from a highly centralized model of governance to one that increasingly emphasizes decentralization and regional empowerment. The early post-independence period prioritized national integration and institution-building, channeling resources through centralized five-year plans that aimed to reduce inherited colonial imbalances. Yet, in practice, development remained skewed toward the coastal urban cores, reinforcing geographical divides.

The decentralization process began in earnest in the 1970s, with the Communal Charter of 1976 granting municipalities a formal role in local governance. However, limited fiscal and administrative capacity at the local level, coupled with austerity policies under the 1980s Structural Adjustment Plan, hindered real progress in spatial equity. The constitutional reform of 1996 marked a turning point by recognizing regions as official administrative entities, paving the way for integrated regional development planning and major public investment in transport and industrial infrastructure. These efforts intensified in the 2000s with national programs such as the National Initiative for Human Development (INDH), the Plan Maroc Vert, and Vision 2010 for Tourism, all of which introduced territorially nuanced approaches to development.

A major leap occurred in the aftermath of the 2011 Constitution, which enshrined “advanced regionalization” as a pillar of national reform. The reorganization of Morocco into 12 regions with greater financial and administrative autonomy represented a significant departure from earlier top-down paradigms. Each region was tasked with developing its own Regional Development Plan (RDP), aligned with national goals but responsive to local conditions. Moreover, environmental sustainability and social inclusion became central through strategies like the National Sustainable Development Strategy (2017), in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Despite these institutional innovations, the promise of regional equity remains largely unfulfilled. Morocco’s regional inequality, as measured by indicators such as the Williamson coefficient, remains high compared to peers with similar administrative structures. The gap in public service access, economic opportunities, and infrastructure between leading and lagging regions is persistent. Rural areas, in particular, suffer from underinvestment and poor connectivity, both physical and digital. Decentralization, though formalized, has not yet translated into meaningful regional autonomy. Regional entities often lack the technical expertise, financial resources, and discretionary power to craft and execute development strategies tailored to their specific challenges.

Recent reforms aim to address these shortcomings. The 2021 New Development Model reorients national strategy toward inclusive growth, territorial equity, and institutional reform, while the 2022 Investment Charter (Law No. 03-22) introduces targeted incentives to attract private investment to underserved provinces, offering territorial investment premiums of up to 15%. These initiatives reflect a growing recognition that economic growth alone will not guarantee convergence; deliberate, place-based policies are needed to foster opportunity where it is absent.

At the heart of Morocco’s current regional development challenge is a structural contradiction: while the country has made undeniable progress in terms of national growth and sectoral modernization, it has yet to overcome the spatial imbalances that threaten to undermine the social contract. This contradiction is not unique to Morocco. Theoretical frameworks such as the Williamson hypothesis propose that regional inequality tends to follow an inverted U-shape, increasing in the early stages of development before declining as growth becomes more geographically diffused. The trajectory that Morocco is currently on—marked by rising inequality despite overall progress—suggests it is climbing the upward slope of this curve.

The stakes are high. Without effective regional policy and genuine decentralization, Morocco risks locking itself into a path of dualistic development—advancing at two paces—where a dynamic, globally integrated core coexists with marginalized and stagnant peripheries. Reversing this trend will require more than administrative reform or infrastructure expansion—it will demand a fundamental shift toward a territorially sensitive development paradigm, where regional equity is not a secondary concern but a central objective of national policy.

This policy brief examines the theoretical foundations of the inverted U-shaped relationship, analyzes Morocco’s current regional inequalities in comparative perspective, explores the root causes of these disparities, and advances policy recommendations aimed at fostering a more balanced and inclusive model of regional development.

The Double-Edged Sword of Economic Growth

Economic growth is widely regarded as the cornerstone of development, offering a pathway out of poverty and toward improved living standards. Yet its spatial distribution is often uneven, producing a mosaic of prosperous and lagging regions within the same national borders. This pattern of divergence is not unique to any single country but rather a structural feature of the development process observed across continents. In both the Global South and, to a lesser extent, the Global North, economic expansion tends to concentrate in regions with pre-existing advantages—such as infrastructure, capital, skilled labor, and markets. As a result, large metropolitan areas like São Paulo in Brazil, Lagos in Nigeria, or Mumbai in India have become economic powerhouses, while rural hinterlands and interior regions continue to struggle to capture the benefits of growth.

The phenomenon is particularly pronounced in developing countries, where institutions are still maturing and spatial planning often remains weak or inconsistent. In such contexts, the forces of agglomeration—where firms and people cluster to benefit from economies of scale and network effects—intensify geographic disparities. Without effective counterbalancing policies, these forces can lead to entrenched regional inequalities, persistent underdevelopment in peripheral areas, and increasing pressure on already congested urban centers. International experience shows that even as national averages improve, territorial divides can deepen, creating “two-speed countries” that face growing challenges to social cohesion and political stability. This dynamic has prompted growing interest among development economists and policymakers in the spatial dimensions of growth, and the urgent need for regionally inclusive strategies that move beyond one-size-fits-all models of national development.

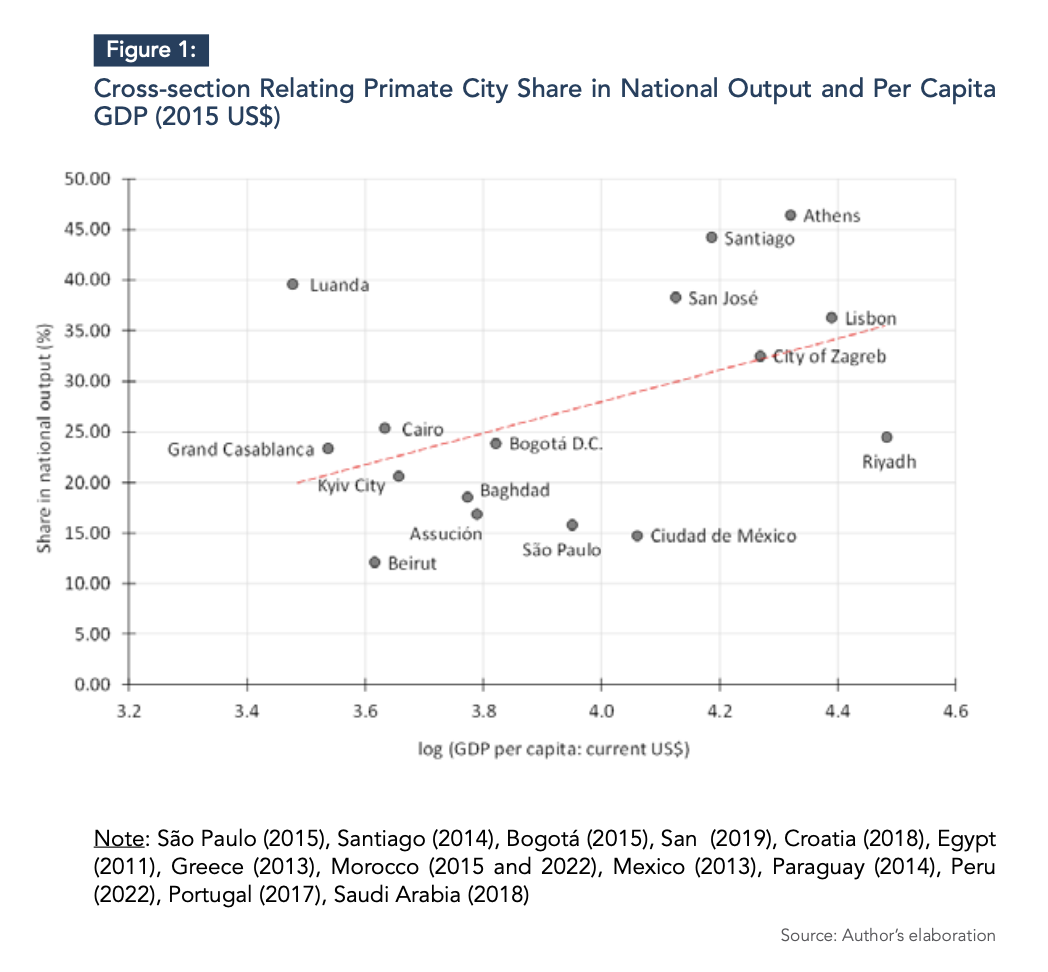

In Morocco, this dynamic is reflected in the outsized role of Grand Casablanca, which alone generates close to one-quarter of national output. Such concentration places Morocco above the expected trend for countries at similar income levels, underscoring the degree to which its economy remains anchored in a single metropolitan hub. Unlike megacities such as São Paulo or Mexico City, whose relative economic shares are smaller within their larger national economies, Casablanca exerts a disproportionate weight more akin to Cairo or Bogotá, where primate cities dominate economic life. Yet it stops short of the extremes observed in places like Luanda or Athens, where a single city can account for more than 40 percent of output. This pattern highlights how Morocco’s growth model continues to reinforce the primacy of coastal cores, deepening the divide with hinterland regions that struggle to capture the benefits of national expansion (Figure 1).

Studies examining whether wealthier regions in Morocco areas grow more slowly or more rapidly than poorer ones have produced mixed results. Due to data limitations, estimates of unconditional beta convergence for per capita GDP are only available for the 21st century—a period characterized by Morocco’s structural reforms and regional integration efforts. These estimates suggest a modest trend of convergence, which has shifted toward divergence in recent years (2015-2022) (Benida et al., 2023).

At the national level, income inequality in Morocco remains structurally high, with the richest 10% capturing nearly 32% of national income—around 12 times the share of the poorest 10% (Dadush and Saoudi, 2019). At the regional level, inequality indicators measured through Williamson’s coefficient of variation—a standard metric of regional disparity—remain elevated and above the average of comparable developing countries, including Chile, Colombia, Egypt, Mexico, Paraguay, and Peru (Figure 1). When combined with per capita GDP levels, these findings align with Williamson’s hypothesis of an “inverted U-shaped curve,” which links inequality to stages of development (Haddad and Araujo, 2023). In early development, weak interregional linkages often exacerbate regional disparities (Bartelme & Gorodnichenko, 2015). Over time, as connectivity improves, disparities are expected to decline. Morocco’s data reflect this trajectory, showing a recent rise in regional inequality as the country advances along the curve (Figure 1). Without targeted policy interventions, the gap between Morocco’s prosperous and marginalized regions risks widening further, with significant social and economic consequences.

The Theoretical Framework: The Inverted U-Shaped Hypothesis

The idea that economic development and inequality are systematically linked was first proposed by Simon Kuznets in 1955, who observed an inverted U-shaped relationship between income inequality and economic growth at the national level (Kuznets, 1955). A decade later, Jeffrey Williamson extended this concept to the regional dimension, postulating that as a country develops, regional disparities first increase, then stabilize, and finally decrease (Ozturk, 2010; Dunford, 2007). This trajectory, often referred to as the Williamson hypothesis, provides a powerful framework for understanding the spatial dynamics of economic development.

According to Williamson, in the early stages of development, a country’s economic growth is often driven by a few “core” regions that have initial advantages, such as access to ports, natural resources, or political power. These regions attract a disproportionate share of investment, skilled labor, and infrastructure, leading to a virtuous cycle of growth that leaves “peripheral” regions further behind. This initial divergence is often characterized by what Gunnar Myrdal termed “backwash effects,” where the growth of the core region drains the periphery of its resources and talent (Myrdal, 1957).

As the economy matures, however, several forces can begin to counteract this trend. The core regions may experience diminishing returns to investment and rising congestion costs, making the peripheral regions more attractive for new investment. Additionally, as the national economy becomes more integrated, “spread effects” or “trickle-down effects” can begin to take hold. These include the diffusion of technology and innovation from the core to the periphery, the expansion of markets, and the development of interregional trade and infrastructure (Balland & Boschma, 2021; Shi, Jin, & Li, 2006). Government policies, such as investments in education and infrastructure in lagging regions and the implementation of fiscal transfers, can also play a crucial role in promoting regional convergence.

The inverted U-shaped curve is therefore a representation of a dynamic process of spatial economic transformation. It is not, however, an immutable law. The height and width of the curve—that is, the peak level of inequality and the duration before convergence begins—can vary significantly across countries, depending on their unique geographical, historical, and policy contexts (Lessmann, 2011). For developing countries today, the challenge lies in managing the upward slope of the curve to minimize social and political tensions, while implementing policies that can accelerate the arrival of the turning point.

Morocco on the Upward Slope: A Comparative Perspective

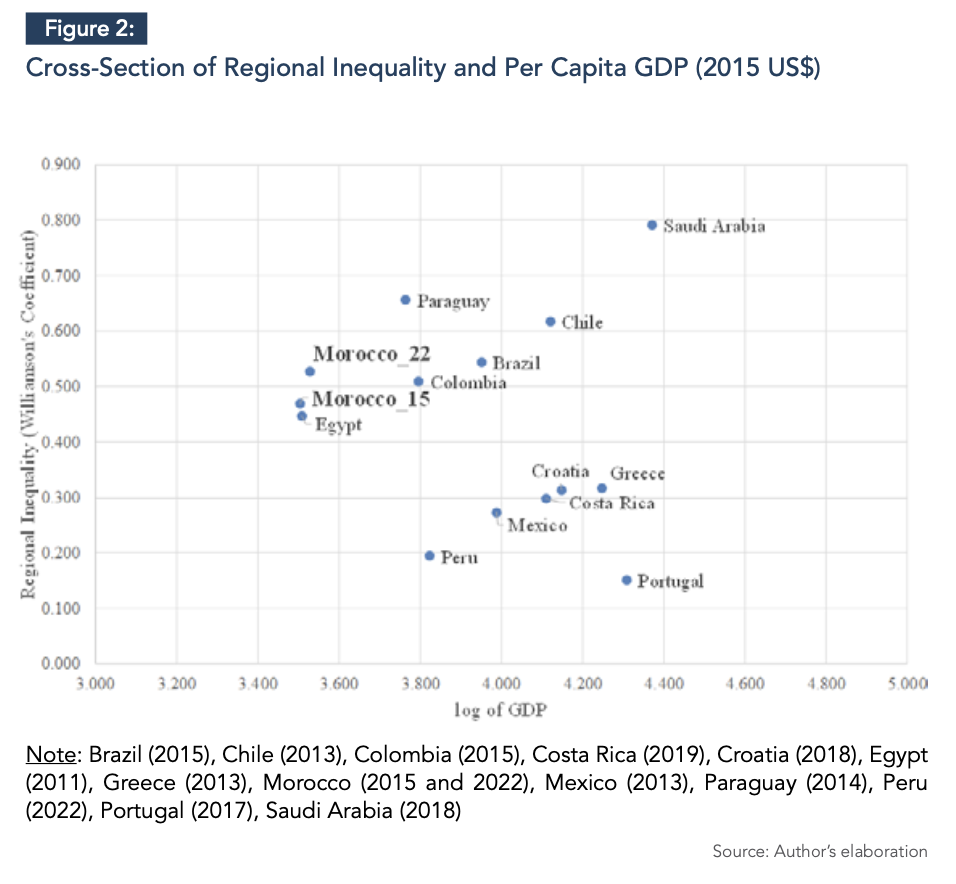

Building on the theoretical framework discussed in the previous section, Figure 2 visually positions Morocco and a sample of peer economies along the inverted U-shaped relationship between economic development and regional inequality. The x-axis represents the log of GDP per capita, while the y-axis captures regional disparity using Williamson’s coefficient, a widely recognized measure of spatial inequality. The data support the hypothesis that regional inequality tends to rise in the early stages of economic development, peaks at intermediate levels of GDP per capita, and declines as economies mature and interregional convergence mechanisms gain strength.

In this context, Morocco’s two data points—labeled Morocco_15 and Morocco_22, reflecting its position in 2015 and 2022—fall clearly on the upward slope of the curve. This indicates that, as Morocco’s economy has expanded in recent years, regional disparities have widened rather than narrowed. Its placement relative to other countries—such as Egypt and Colombia, which also cluster along the ascending segment—suggests that Morocco is not an outlier in this trajectory. However, Morocco’s inequality levels are noticeably higher than those of several peers at similar income levels, including Peru and Mexico, which appear closer to the peak of the curve or even slightly on its descending side.

The contrast becomes sharper when compared to more advanced economies like Portugal, Costa Rica, and Greece, all of which display significantly lower regional inequality coefficients despite higher levels of GDP. At the opposite extreme, Saudi Arabia’s high GDP is coupled with unusually high regional inequality, likely reflecting a concentrated resource-driven growth model that has accentuated territorial imbalances.

Morocco’s position on the rising slope of the curve confirms the theoretical expectation that inequality tends to increase during the early-to-middle stages of growth. This reflects the cumulative advantages of “core” regions that attract disproportionate investment and talent, amplifying disparities with lagging areas. However, as Morocco expands its interregional infrastructure, enhances institutional decentralization, and implements targeted spatial policies, these disparities are expected to decline over time. In short, Morocco’s current position does not defy the model—it validates it, while also highlighting the urgency of accelerating the transition toward the convergence phase.

In fact, the concentration of wealth and economic activity in Morocco’s coastal regions, mainly Casablanca-Settat, Rabat-Salé-Kénitra, and Tangier-Tetouan-Al Hoceima, is striking. These three regions alone account for 58.5% of the national GDP in 2023 (HCP, 2025). This leaves the remaining nine regions, particularly those in the hinterland and the middle and southern parts of the country, to share the rest.

This spatial imbalance is reflected in a wide range of development indicators. Access to quality healthcare and education is significantly better in the more prosperous regions. For instance, the number of people per doctor in the Draa-Tafilalet region is more than double the national average (Dadush and Saoudi, 2019). Similarly, the urban-rural divide remains a major axis of inequality, as rural areas continue to face deficits in infrastructure, limited access to basic services, and fewer economic opportunities (Atia & Samlali, 2021). This disparity is a direct legacy of the colonial era that drew a stark distinction between a “useful Morocco” (Maroc utile) and an “useless Morocco” (Maroc inutile)—a dichotomy that continues to shape development patterns today.

The Root Causes of Regional Disparities in Morocco

The persistence—and, in recent years, the worsening—of regional inequality in Morocco can be traced to a confluence of historical, economic, and political factors.

The Legacy of Centralization: Morocco’s development model has historically been highly centralized, with economic and political power concentrated in the coastal metropolis. This has led to a pattern of public investment that has favored the already prosperous regions, reinforcing their economic dominance. The colonial legacy of a dualistic spatial structure has been perpetuated in the post-independence era, creating a deeply entrenched pattern of uneven development.

The Nature of Economic Growth: Morocco’s economic growth in recent decades has been driven by sectors such as manufacturing—particularly in automotive and aeronautics—and services, which are heavily concentrated in the coastal regions benefitting from agglomeration economies. While these sectors have significantly boosted national economic performance, they have generated limited spillover effects for other parts of the country. By contrast, the agricultural sector, which remains the main employer for other parts of the country, is highly vulnerable to climate variability and has not achieved comparable productivity gains.

Weak Interregional Linkages: The “spread effects” identified by Myrdal, Hirshman, and Williamson identified as key drivers of convergence are contingent on strong interregional linkages. In Morocco, these linkages remain relatively weak. Transportation infrastructure is more developed in the coastal regions, while the flow of goods, capital, and knowledge between the core and the periphery remains limited. This has hindered the ability of lagging regions to fully participate in—and benefit from—the growth of the national economy.

The Limits of Decentralization: In recent years, Morocco has embarked on an ambitious process of “advanced regionalization,” aimed at devolving more power and resources to the regional level. However, implementation has been hampered by several challenges. Regions continue to lack the financial and administrative autonomy necessary to design and implement their own development strategies, while the central government retains significant control over budgeting and decision-making. Furthermore, the capacity of regional and local entities to plan and execute development projects is often limited. As a result, the decentralization process has yet to deliver on its promise of a more balanced and inclusive development model. In some cases, it has even been argued that resource distribution through decentralization has reinforced existing inequalities (Houdret and Harnisch, 2017).

Final Remarks

The spatial trajectory of economic development rarely follows a straight path. It unfolds unevenly, shaped by the interplay of history, geography, institutions, and opportunity. In Morocco’s case, the past two decades have brought undeniable progress: GDP has risen, industrial exports have diversified, and flagship infrastructure projects have placed the country more firmly on the global map. Yet behind this macroeconomic momentum lies a more fragmented territorial landscape—one in which gains have accrued unevenly, and the pace of progress varies sharply across regions.

As this brief has argued, such divergence is not unique to Morocco, nor is it necessarily a sign of policy failure. Rather, it is consistent with the inverted U-shaped relationship between development and regional inequality—a dynamic first theorized by Kuznets and later extended to spatial contexts by Williamson. Within this framework, countries at low to middle stages of development often experience rising regional disparities, as a handful of advantaged regions become engines of growth while others struggle to keep pace. Morocco appears firmly situated on this upward slope, where inequality is deepening even as the broader economy expands.

However, this position on the curve is not without its advantages. For countries like Morocco, continued urban agglomeration can still generate productivity gains, innovation spillovers, and structural transformation. The growth of metropolitan hubs like Casablanca and Tangier is not merely a symptom of imbalance—it remains a source of national dynamism. The real challenge lies in managing this agglomeration so that it becomes a force for broader territorial inclusion rather than one of entrenchment and exclusion.

This requires strategically channeling the benefits of core-region growth toward the rest of the country. Policy should prioritize the creation of interconnected economic spaces, where less-developed regions are not left to compete in isolation but are meaningfully integrated into national value chains. Industrial policy, for instance, should move beyond place-neutral incentives and instead encourage productive complementarities between core and peripheral regions—facilitating supplier networks, shared logistics, and knowledge transfer.

Moreover, infrastructure investment must be rethought—not only in terms of physical reach but also in terms of functional connectivity. Morocco’s past two decades have seen heavy investment in highways and ports, but attention must now shift toward transversal routes and under-connected provinces. The same applies to digital infrastructure, which remains uneven across regions despite its growing centrality to employment, education, and entrepreneurship.

Addressing regional inequality also requires territorially grounded human capital strategies. Rather than deploying uniform vocational programs nationwide, education and training systems should be aligned with local economic structures. A promising approach would be to devolve part of this mandate to regional authorities—better positioned to identify sectoral strengths and labor gaps—and to foster partnerships between local industries and educational institutions.

Finally, governance matters. The vision of advanced regionalization outlined in Morocco’s 2011 Constitution remains only partially fulfilled. Regional councils continue to face constraints in fiscal autonomy, technical capacity, and planning authority. For spatial policy to be effective, regions must become genuine actors of development, empowered to shape investment priorities and coordinate cross-sectoral initiatives. The national government, in turn, should adopt a more enabling role—setting broad strategic goals while allowing regional experimentation and innovation within clear accountability frameworks.

In short, for countries navigating the ascending portion of the regional inequality curve, the imperative is not to curtail agglomeration but to ensure it radiates outward. Growth must no longer be concentrated in enclaves of efficiency and exclusion; it must be distributed through networks of connection, complementarity, and coordinated policy effort. Only then can the promise of national development resonate more evenly across Morocco’s diverse territorial fabric.

Moreover, this nuanced reading of Morocco’s regional dynamics adds a critical spatial dimension to the broader debate on the middle-income trap. While the national economy may be advancing, the persistence and deepening of territorial disparities suggest that growth is becoming spatially locked—concentrated in dynamic urban hubs while bypassing vast peripheral regions. This risks creating a middle-income “spatial” trap, where national development stagnates not due to a lack of innovation or investment, but because the benefits of progress remain geographically constrained. Addressing this spatial inequality is thus not only a matter of territorial justice but a strategic imperative for sustaining long-term, inclusive development.

References

Atia, M., & Samlali, S. (2021). Government efforts to reduce inequality in Morocco are only making matters worse. Middle East Research and Information Project (MERIP).

Bartelme, D., &Gorodnichenko, Y. (2015). Linkages and economic development (NBER Working Paper No. 21251). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Balland, P.-A., & Boschma, R. (2021). Complementary interregional linkages and smart specialisation: An empirical study on European regions. Regional Studies, 55(6), 1059–1070.

Benida, O., Allali, K., Ramou, H., & Fadelaoui, A. (2023). La dimension économique dans le découpage régional au Maroc : analyse de la convergence des régions. African Scientific Journal.

Dadush, U., & Saoudi, H. (2019). Inequality in Morocco: An international perspective (Policy Paper No. PP-19/13). Policy Center for the New South.

Dunford, M. (2007). Regional inequalities. In J. Michie (Ed.), The handbook of globalisation (pp. 485–497).

Haddad, E. A., & Araujo, I. F. (2023). How can Moroccan regions and sectors help to achieve the ‘New Development Model’ goals? (Policy Paper No. PP-07/23). Policy Center for the New South.

Haut-Commissariat au Plan (HCP). (2025). Les comptes régionaux : Produit intérieur brut et dépenses de consommation finale des ménages – année 2023. Royaume du Maroc.

Houdret, A., & Harnisch, A. (2017). Decentralisation in Morocco. The Current Reform and Its Possible Contribution to Political Liberalisation. DIE Discussion Paper.

Kuznets, S. (1955). Economic growth and income inequality. The American Economic Review, 45(1), 1–28.

Lessmann, C. (2011). Spatial inequality and development: Is there an inverted-U relationship? (CESifo Working Paper No. 3622). Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo).

Myrdal, G. (1957). Economic theory and under-developed regions. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co.

Ozturk, L. (2010). Williamson-Kuznets’ hypothesis: Some evidence from Turkish provincial data. Reforma, 2010.

Shi, M., Jin, F., & Li, N. (2006). Interregional economic linkage and regional development driving forces based on an interregional input-output analysis of China. Acta Geographica Sinica, 61(6), 593–602.