Publications /

Opinion

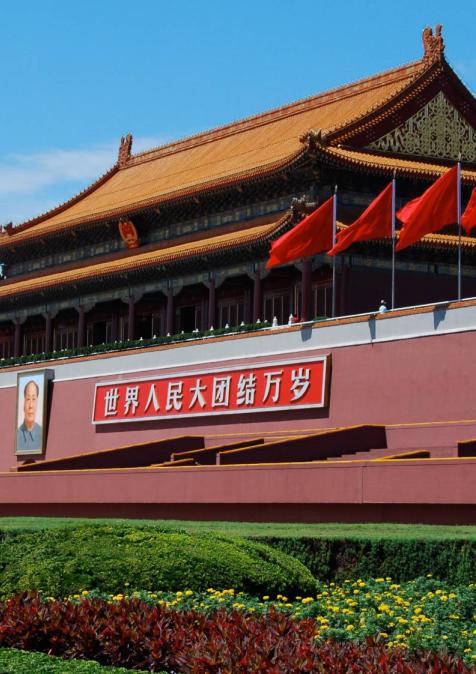

On 1 October, China marked the 76th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic. Few nations in modern history have experienced such a remarkable transformation in so short a time. In just over seven decades, China has ascended from poverty and fragmentation to become a technological, economic, and diplomatic powerhouse of global significance. This trajectory—driven by strategic planning, institutional stability, and a steadfast belief in the state as a catalyst for development—has profoundly reshaped the balance of international power.

Yet, this ascent has also generated mounting unease, particularly in the West, where China is often seen less as a partner and more as a potential threat. These anxieties, however, may say more about Western insecurities in the face of shifting global dynamics than about the realities of China itself. Broadly speaking, these fears can be understood across five main dimensions.

The first dimension is ideological. Many in the West continue to interpret China through the outdated prism of Soviet experience—a profound misconception that obscures the distinctive nature of "socialism with Chinese characteristics." Chinese socialism departs markedly from the rigid Leninist model: it is pragmatic rather than revolutionary, evolutionary rather than confrontational. Its central objectives are social harmony, national rejuvenation, and material prosperity. This model embodies an indigenous path to modernity, grounded in historical continuity and cultural specificity, rather than the imposition of a universalist ideology. Understanding this uniqueness is essential to any meaningful understanding of China’s ideological distinctiveness.

The second dimension is demographic and economic. With a population of over 1.4 billion and a vast domestic market, China has already surpassed the United States in purchasing power parity and is likely to overtake it soon in absolute economic size. This prospect deeply unsettles policymakers in Washington and Brussels, whose symbolic and material leadership is steadily waning.

History reminds us that hegemony is never eternal. Just as Britain ceded global primacy to the United States in the twentieth century, it is only natural that a civilization of such antiquity should reassert its historical centrality in the twenty-first.

The third dimension is structural. China's ascent unfolds at a time when much of the West is gripped by crises of confidence, political fragmentation, infrastructure decay, and economic stagnation. While Europe and the United States wrestle with internal divisions and eroding social cohesion, China remains resolutely focused on its long-term objectives—innovation, infrastructure, energy transition, and technological modernization. Admittedly, China faces its own challenges, from global trade headwinds to demographic shifts, yet its vast domestic market and strategic coherence in policymaking provide a degree of resilience that few nations can rival.

The fourth dimension is civilizational. China's rise challenges the deeply ingrained Western assumption that progress, rationality, and modernity are inherently Western attributes. For centuries, Eurocentric narratives have cast world history as a linear continuum—beginning in Greece, refined in Rome, and culminating in Washington. The re-emergence of China, shaped by Confucian ethics, a deep sense of continuity, and a worldview founded on harmony rather than domination, disrupts this long-standing narrative, illuminating the true diversity of global civilization. It reminds us that the centre of gravity of human progress has always been plural, and that Asia, far from being a mere periphery, was for millennia the heart of the world’s economy and culture.

Finally, the fifth and often overlooked dimension concerns the role of the state. In recent decades, the West has grown increasingly skeptical of government, associating it with inefficiency, bureaucracy, and privilege. Under the influence of liberal orthodoxy, the state has been reduced to a reluctant regulator—its intervention seen as an obstacle rather than a necessity. Yet this minimalist vision neglects a fundamental reality: there are collective responsibilities—such as security, education, social stability, and justice—that no private actor can fully assume.

In the Chinese tradition, shaped by centuries of imperial governance, the state is not an adversary but the ultimate arbiter of social life—the guarantor of order, the custodian of harmony. It is the backbone of civilization, the institutional expression of the collective will. The challenge, of course, lies in ensuring its efficiency, integrity, and meritocracy, so that public service becomes an instrument of excellence rather than a vehicle of privilege. This perspective on the role of the state in governance, which emphasizes collective responsibility and social harmony, could help reshape global governance norms and influence the future of global politics.

Thus, 1 October is not merely a national celebration for the Chinese people; it is also a moment of reflection for the world. It reminds us that civilizational cycles are natural, that global leadership is never immutable, and that the future belongs not to those who fear change but to those who understand and adapt to it with wisdom. Rather than viewing China as a threat, the West—and indeed the Global South—should recognize it as a partner in redefining the norms of global coexistence.

For, as the observation attributed to Confucius affirms, “The wise man adapts himself to circumstances, as water shapes itself to the vessel that contains it.” This adaptation is not merely a choice but a necessity for the West in the face of China’s rise. And perhaps, in this new century, Napoleon’s long-echoed warning has at last found its fulfillment: “China is a sleeping giant. Let her sleep, for when she wakes, she will move the world.” The giant has awakened—and the world, indeed, is moving.