Publications /

Opinion

The report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released at the beginning of August, left no room for doubt. According to its estimates, it will be necessary to accelerate the pace of global containment of carbon emissions if the expected increases in global average temperatures are to be kept below 2 or 1.5 degrees Celsius, with correspondingly less-dramatic climatic consequences. Even if emissions of greenhouse gases are reduced over the next few decades, global warming will continue for at least another century.

To give an idea of what's at stake, look at the numbers in a paper by Jean Pisani-Ferry at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Starting from pre-pandemic emission levels (emissions declined during lockdowns, but have rebounded), the stock of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere compatible with limiting the global temperature increase to 2 degrees Celsius would be achieved in less than 25 years. The period shortens to seven years in case the limit is to be reduced to 1.5 degrees.

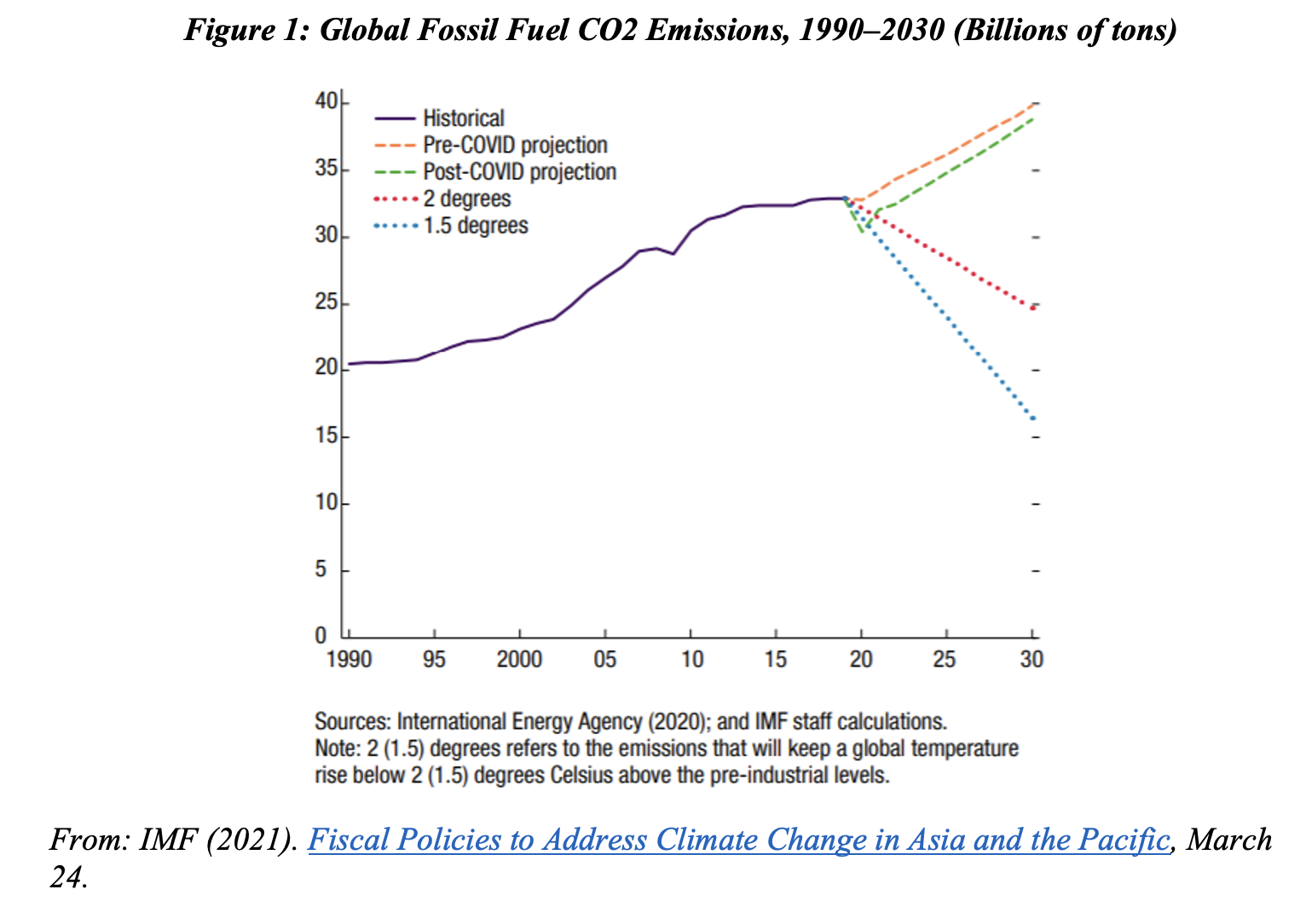

Figure 1 shows projected global fossil fuel CO2 emissions, according to the International Energy Agency and IMF staff calculations. After falling during the pandemic, they are projected to rise by about 20% by 2030. This contrasts with the 25% to 50% decline consistent with the 1.5 to 2 degrees warming limit. Limiting temperature rises will require less smoothness and gradualism of emissions tapering than was expected until recently.

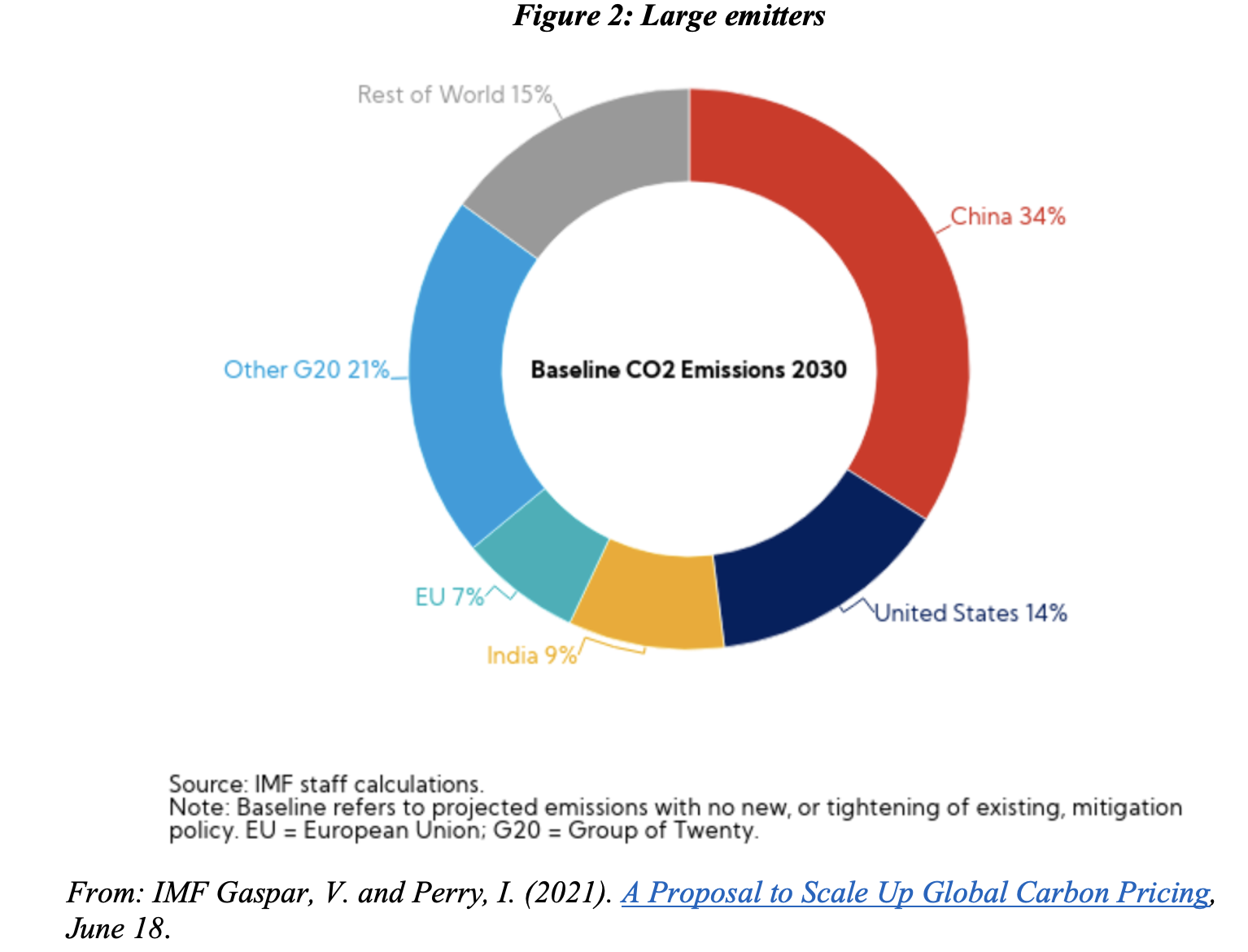

Acknowledgement of the urgency appears in commitments by countries responsible for around 70% of global carbon emissions and global GDP to reach ‘zero emissions’ by 2050 or 2060 (IEA, 2021). Figure 2 shows the baseline CO2 projection of emissions in 2030, displaying China and United States as the world’s largest emitters.

However, decarbonization will be a bumpy road. The transition to zero emissions will involve three simultaneous economic processes (Pisany-Ferry, 2021):

First, a significant change in the relative prices of goods and services, with prices starting to reflect the intensity of emissions of carbon, the price of which will have to rise from zero to significant levels. Gaspar and Parry (2021) proposed that, at international level, measures be taken to reach a carbon price equal to or greater than US$75 per metric ton by 2030.

Such a carbon price may be established and charged explicitly and/or indirectly through the effects of regulations or limits on uses. Decarbonization will be negligible if the price of carbon remains that of a ‘free good’ provided by nature. Carbon prices will also have to be among the factors influencing people's behavior and lifestyle.

Additionally, workers will have to be relocated from carbon-intensive activities to greener substitutes. There will be not only the challenge of labor reskilling, but also of ensuring that new jobs are sufficiently created in dynamic activities. It is known, for example, that the production of electric cars requires less labor than that of combustion engine vehicles.

Third, there will be accelerated obsolescence of existing stocks of physical assets (machinery and equipment, buildings, vehicles) and intangible assets associated with carbon-intensive activities. The counterpart to this will have to be accelerated investment in new assets to replace what is being phased out.

The good news about such replacement is that the evolution towards cleaner technologies with declining costs is taking place. The bad news is the presence of obstacles to such investments, particularly in the case of green infrastructure in non-advanced countries (Canuto, 2021).

The transition of decarbonization will possibly have regressive income impacts. For example, real estate to be rebuilt or retrofitted corresponds to the largest share of assets of people in the lower half of the income pyramid. Direct carbon taxation will have different impacts on different urban groups. Likewise, it is important not to lose sight of the re-qualification and employment needs of workers directly affected. It will be important to ensure income transfer mechanisms within countries and internationally associated with carbon pricing, to mitigate the regressive impacts of combating climate change.

The trajectory of decarbonization will also have implications for public budgets and debt; see Zenios (2021) in the case of Europe. In addition to compensatory expenditures for the regressive impacts of carbon pricing mentioned above, public expenditure on infrastructure to enable the transition will be required. Except in the unlikely event of full coverage of expenditures with some carbon tax, the trend will be for increasing public debt. In this case, without intertemporal injustice, as future generations will be grateful not to have to live permanently with an even more adverse climate.

What about GDP and its growth during the transition? Here the duality of impacts discussed above is repeated. On the one hand, there will be capital destruction, in addition to a relative price shock that, as Jean Pisani-Ferry observes, bears similarities to the “supply shock” that happened when oil prices suddenly and drastically soared in the 1970s, including by temporarily reducing potential growth. But while oil prices were later reversed, the carbon price cannot be allowed to do so if the world is to be decarbonized. If the need for greater investment as a share of GDP to accompany decarbonization collides with supply capacity limits, consumption will have to adapt downwards throughout the transition.

On the other hand, cleaner technologies will also generate opportunities to increase productivity. In any case, the socioeconomic return from decarbonization must include preventing heatwaves, floods, hurricanes, droughts, floods, and storms like those of this year from becoming even more intense and frequent. The cost of that would involve even higher GDP losses for nations.

The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author.