Publications /

Opinion

This year, under the patronage of His Majesty King Mohammed VI, the OCP Policy Center (OCPPC) - in collaboration with the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMFUS) - hosted and organized the fifth Atlantic Dialogues, gathering over 300 high-level international public- and private-sector leaders from the Atlantic Basin to discuss cross-regional issues ranging from economic and social development, security and trade, to migration, resources, and energy. This year’s event, located at the Hotel La Mamounia in Marrakech from the 14th to the 16th of December 2016, addressed the theme "Changing Mental Maps: Strategies for an Atlantic Area in Transition". The participants, coming from the various sectors of the economy and all quadrants of the Atlantic, engaged in a series of interactive panels and smaller break-out sessions on the above-mentioned topics. As countries of “the South” have become aware of the potential they represent, they aspire to a better cooperation amongst themselves accompanied with a better integration in the entire Atlantic basin. In this framework, understanding past and previous global contexts becomes crucial for such economies, through innovative and sound public policy, to incorporate the complex and evolving global economy.

The Evolving Global Context: A Peculiar Globalized World To Bear in Mind

As of the 1990s post-Cold War era, global economic structures have been shifting: old patterns of stability have broken up while new ones continue to emerge. In this blurry context, emerging market economies have gained considerable momentum, becoming key actors within the new global economy and benefiting from the early stages of globalization, commodity booms, and the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Today, however, this concept of globalization driven by international trade, foreign investment, and information technology is being revisited as both developing countries and advanced countries face negative externalities from this process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments. Indeed, globalization has had two major side-effects on regional and country-specific macro/micro indicators: (i) decreases in inter-country inequalities allowing for better integration of EME’s into the global economy, paralleled by (ii) increases in intra-country inequalities at a global scale. This second side-effect, some argue, might be generating pressures on the governance systems, an important puzzle piece amongst other factors, which could explain the emergence of new forms of violent extremism or perhaps the rise of more populist nationalist mindsets in Europe and abroad with the rise of far right politics - in European elections results, the BREXIT outcome in Great Britain, and the recent election of Donald Trump in the United States.

The East-Asian “Miracle”: Lessons from Successful Integrations Into The Global Economy?

Throughout the 20th and 21st century, developed and developing countries have experimented with different paths to development: modernization and dependency theories are two major schools of thoughts that attempt to explain, understand, and trigger past, present, and future national and regional development and growth strategies. Some regions, such as Latin America, when structuring their development path opted for Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) in order to reduce its foreign dependence and thus replace foreign import with domestic production. Across the globe however, the East Asian Tigers, or EATs - such as Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Taiwan - China, and Thailand, focused their development outward, resulting in export-led growth strategies using trade and economic policy in order to speed up the industrialization process of their respective countries by exporting goods for which they had a comparative advantage. Indeed, these “Dragons” experienced rapid industrialization, high technological development and sustained significant growth rates. These countries started by getting the basics right; the principal engines of growth were private domestic investment coupled with rapidly growing human capital. These countries sustained high investment levels through high levels of domestic financial savings. In addition, agriculture experienced rapid growth and productivity improvement while population growth rates declined more rapidly compared to other parts of the developing world. As mentioned by the IMF, the EATs had tremendous growth rates of output per person (above 6%) for over 30 years.

One important component to note is that some Tigers had a “better-educated” labor force and more effective system of public administration. Then, the real effort had to take the lead: (i) government intervention to promote development, and in some cases the development of specific industries, (ii) elevated (20% of GDP on average between 1960 and 1990) investments (including private) in human capital and productivity, and (iii) public policies geared towards accumulation, efficient allocation, and rapid technological catch-up that bolster savings, build strong financial markets, and promote investment with equity. Nonetheless, according to Rodrick(2011), “development requires structural changes within countries able to diversify away from agriculture and other traditional products in order to further develop”. Both development strategies had different outcomes, and both regional and global contexts greatly influenced the successes and/or failures of these schools of thought. Needless to say, growth in developing countries is dependent on overcoming several obstacles or country characteristics, such as weak institutions, political instability, reduced infrastructure, and inadequate economic policies, which manifest themselves in several African countries today.

An Emerging Continent: What Instruments Can African Economies Exploit To Integrate The New Global Context?

The rise of Pacific Asian nations as new economic zones of influence, mentioned above, could serve as a lesson for African countries who wish to pursue similar attitudes when contextualizing and tackling their structural transformations strategies. For that, each country and region will need to better understand their comparative advantages while sequencing and prioritizing public policies to come. The Atlantic basin trajectory shows the region’s strength given the overwhelming rise in Asia’s economic force. The region has fought to hold a strategic place in the global economy, as a result of the systemic importance the northern part of the region represents: The United States and the European Union constitute over 51% of global GDP (at market prices, and constant dollar) and more than 35% in purchasing power parity. They also account for over 25% of global exports, 30% of imports, and 70% of the global outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) and 60% of incoming FDI. However, the area remains very heterogeneous with significant differences between its economies: while the US, EU and Canada account for nearly 55% of global GDP, the Latin American and African economies on the Atlantic coast account for about 6% and 1% of global GDP, respectively.

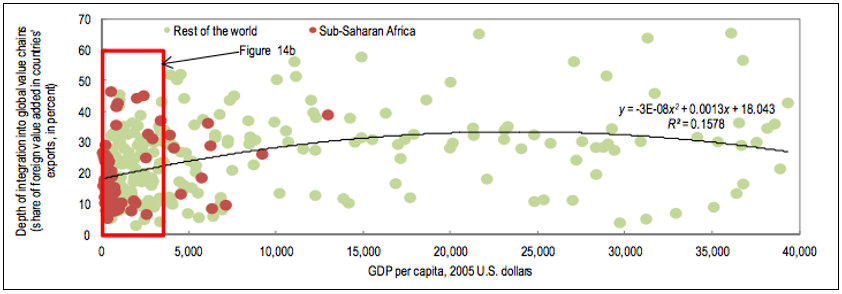

Although the picture seems grim, in the first decade of the 21st century the dynamics have been shifting in a positive direction: six of the 10 fastest growing economies of the globe are located in sub-Saharan Africa: Mozambique, Rwanda, Angola, Nigeria, Chad and Ethiopia. As a region, sub-Saharan Africa grew at an average of 5% during the first 15 years of the new millennium, a major shift from the lost decade of the 1980s. For Africa, the potential gains from increased regional integration could be further increased through its integration in Global Value Chains (GVC), using perhaps Latin America (with Brazil as a major Atlantic Partner) as a bridge that reignites the cooperation between both sides of the South Atlantic. Sub-Saharan Africa’s progress (figure 1), for example, in connecting to GVCs will further deepen the process of economic integration. According to the IMF’s Trade Integration and Global Value Chains in Sub-Saharan Africa - In Pursuit of the Missing Link (2016) report, there are “still ways to go to better integrate in GVCs.” This requires, according to the study, higher levels of activity and income growth over time (experienced in South East Asian and Eastern Europe, for example).

“The results [from the study] highlight the potential sectors where regions could build on its comparative advantages, provided the business environment is sufficiently conducive.”

Figure 1: Depth of Integration in Global Value Chains and Real GDP per Capita, Average 1991-1995 and 2008-12 (full country sample)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators; Eora database; and IMF staff calculations.

In the Northern part of the continent, Morocco - a country that has maintained stability - has the opportunity to become a central player in the development of ties between (i) Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa, (ii) the MENA region and Sub-Saharan Africa, (iii) North-South and East-West Africa, and finally (iv) the Americas and the South Atlantic African nations.

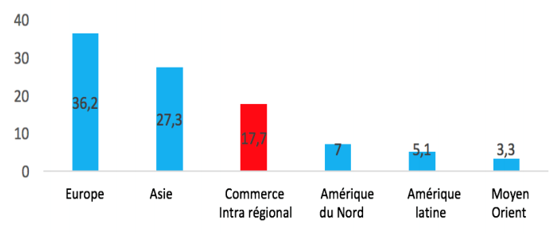

Meanwhile, the country, will need to invest in new trade partnerships through the structure of its trade and financial relations with Europe, whilst remaining bound to a region that is facing structural difficulties and whose growth prospects remain unfavorable. Given this complex but evolving environment, Morocco and other countries “caught between the rapid-growing low-income countries with abundant and cheap labor, and middle-income countries that are able to innovate quickly”, will need to rethink and reformulate their growth strategies in order to better position themselves in the global value chains while preparing to compete in international markets for goods and services with high-skill-intensive labor and more sophisticated technological inputs. It will also become essential in the short and medium term to recover competitive margins in low-skill-intensive activities, to continue reforming the macroeconomic management framework, and to strengthen ties with dynamic Sub-Saharan countries. The opportunities offered by global value chains GVCs in the transformation of Africa’s economies are notable. They would allow for an opening up to new competitive activities and improvement of sector performances in manufacturing, agriculture, and services, while also increasing diversification and technological sophistication of exports (figure 2). Regional value chains should also play a significant role in offering opportunities for local producers – including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – to access fast-growing and more easily accessible markets within Africa.

Figure 2: Export Share of Africa by Destination, 2014

Source: WTO, International Trade Statistics, 2015

Starting from a particularly low base, Africa is the continent that has accelerated intra-regional trade the most since early 2000s. For African countries, trade within the continent has reached over 17% of the region’s total exports in 2014, compared with only 10 percent in 1995 and 2000. Higher trade openness should allow for job creation to absorb the growing working age population, and allow African economies to benefit from technology transfers and integration into global value chains, this of course if investments in human capital, R&D, and innovation follow. Expanding intra-regional trade and regional markets could also boost incentives for domestic production, especially in labor-intensive manufacturing sectors, consequently attracting higher investments from abroad. According to the analysis in Atlantic Currents, African economies are the least integrated with one another, while the total trade figures of the Atlantic basin economies show 58.5%. The banking sector, often dominated by foreign players, is witnessing the emergence and establishment on the African continent of several banks such as those of Morocco, Nigeria and South Africa in the last 10 or 15 years. It is important to note that these countries have not only acquired a sophisticated banking sector but also triggered the diversification of the industry.

The Atlantic Dialogues – Creating A Public Policy Cohesiveness In A New South-to-South Approach

Many of the questions that policymakers are addressing today revolve around: how can African nations focus on inclusive growth while addressing the issues of weak institutions, overwhelming dependence on low-skilled workforce, political instability, inadequate industrial policies, security and extremist threats, climate change, ongoing demographic booms, and urgent needs for external development financing? How can countries develop strong partnerships with neighboring countries while addressing the mismatch between the strong political ambitions African leaders hold and the unforgiving economic realities they face?

The above-mentioned indicators of development and approaches to inclusive growth are only one aspect of the development story that will be told in generations to come. There are important underlying factors within the parameters we have examined which are part of the discussion. While deliberating on integrating GVCs, improving productivity, triggering growth and context base industrialization, policymakers are not all aligned on (i) the sequencing aspect of public policies and (ii) the read on the evolving global scenario. The technological advances are happening at record speeds while the political structures are also being significantly challenged.

Events such as the Atlantic Dialogues allow for such new ideas and concepts to flourish. When inviting numerous experts from different sectors of the economy, the OCP Policy Center and German Marshal Fund attempt to create a platform that introduces ways to change mental maps, touching upon (i) the evolving structure of Africa’s international cooperation with numerous external partners (bilateral, regional or multilateral), (ii) the great divide between the challenges of a post Arab spring MENA region and a heterogeneous sub-Saharan African development, (iii) the declining ODA, imports, and investments, and (iv) low levels of intra-African trade and investments. During the launch of the Atlantic Currents, many points were raised regarding the elaboration of an African Atlantic community with a specific role in the continental architecture. In this setting, policymakers and the Emerging Leaders program rethink and elaborate national and regional-specific policies taking into account the evolving global and regional contexts to better position African economies in (i) the transforming global value chains, (ii) the shifting growth dynamics, (iii) the changing development financing mechanisms, and (iv) the rapidly growing education challenge. These points all position themselves in a context of lack of public resources and financing, which economist and policymakers realize marks a new era of development financing that involves the collaboration between public and private sectors. What is sure is that more off-the-record conferences such as the Atlantic Dialogues, where policymakers are allowed to be creative and think outside the existing framework of thought, think the unthinkable, will be necessary in order to find new approaches to development in a rapidly shifting global scenario; approaches that require north-to-south, south-to-south, and south-to-north discussions aiming at addressing the urgent issues of our time.