Publications /

Opinion

Brazil has been suffering from anemic productivity growth. This is a major challenge because in the long run, sustained productivity increases are necessary to underpin inclusive economic growth. Without them, increases in real labor earnings tend to conflict with global competitiveness; collecting taxes in order to fund government expenditures on infrastructure and social policies becomes a heavy burden; returns to private investment becomes harder to achieve; and ultimately citizens will have less access to high-quality goods and services at affordable prices. The focus on urgent fiscal reforms adopted by the new government– public spending cap, social security reform (Canuto, 2016) – must be accompanied by action on the productivity front.

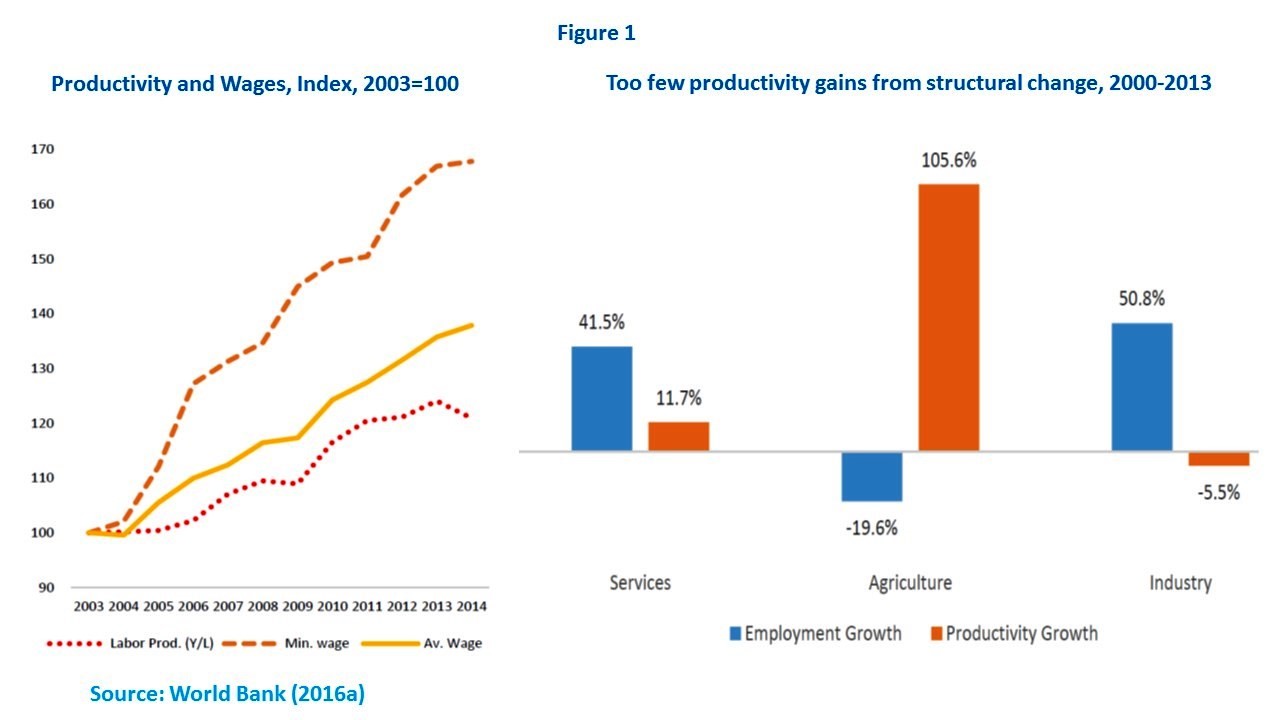

Brazil’s recent social and economic progress was achieved without major productivity growth. Both minimum and average wages rose a lot faster than labor productivity, and employment moved toward sectors with few opportunities for productivity growth (Figure 1).

According to estimates reported in World Bank (2016a), Brazil’s Total Factor Productivity (TFP) increased at an annual rate of 0.3% from 2002 to 2014 – and only 0.4% p.a. during the roaring years from 2002 to 2010. Two-thirds of Brazil’s GDP increase can be accounted for by higher quantity and quality of labor being incorporated in the economy. Only 10% can be attributed to TFP gains.

Demographic trends – a growing working-age population - leading to labor force growth were responsible for 1.1 percentage points to annual GDP growth in 2002-2010, while increases in labor force participation, especially among women - (Agenor and Canuto, 2013) (Canuto, 2013a) - contributed about 0.6 percentage points. Better access to education accounted for about 0.7 percentage points of average growth in the same period. Since the investments-to-GDP ratio remained at or below 20%, it is not surprising that growth in the capital stock contributed only about 0.9 percentage points to growth on average. In labor productivity, which includes the gains from capital deepening as well as TFP, Brazil lagged behind most of its peers over the period.

It is now widely accepted that a systematic increase in Brazil’s labor productivity and TFP will be needed if the growth-with-social-inclusion that prevailed in the 2000s is to return. But how can Brazil come up with these productivity improvements?

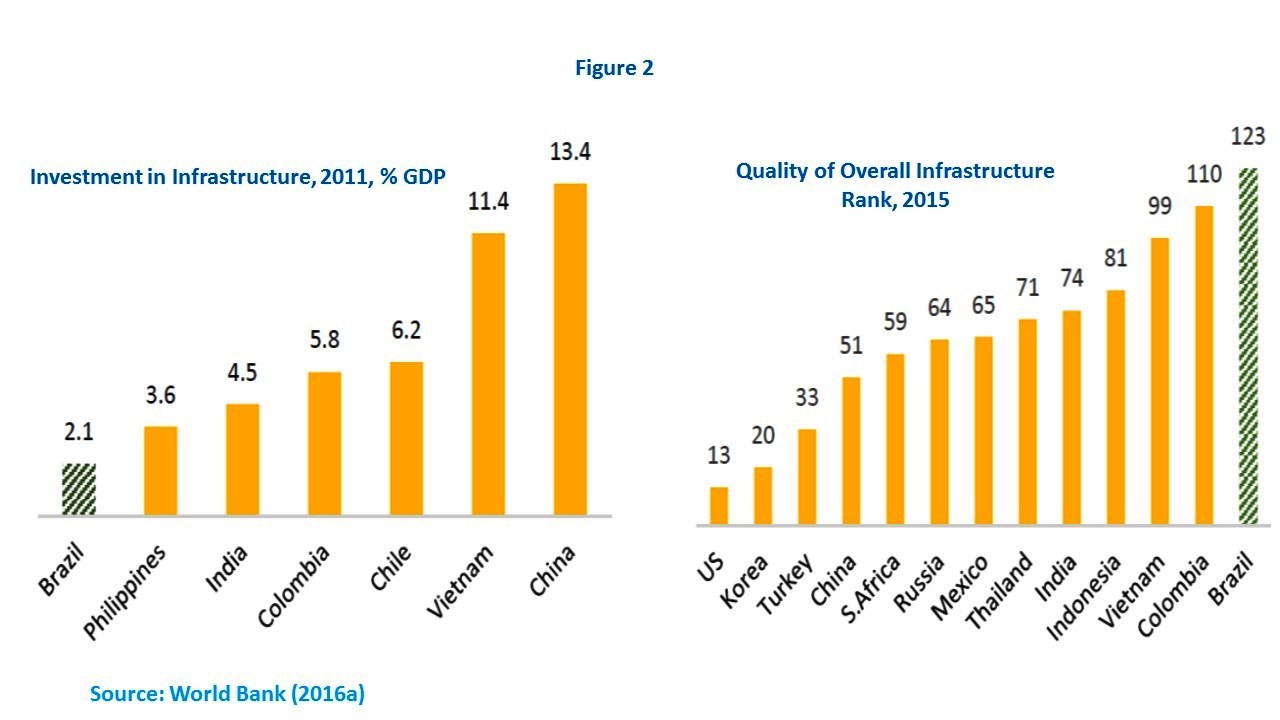

One obvious source of productivity gains is infrastructure. In addition to being a source of gross fixed capital formation, sustainable investments in infrastructure would alleviate bottlenecks that became increasingly tight as the economy expanded:

“For at least the past two decades, investment in infrastructure in Brazil has been below the rate of natural depreciation. The rate of infrastructure investment needed simply to offset depreciation has been estimated to be of the order of 3 percent of GDP (…). In Brazil, total investment in infrastructure has been less than 2.5 percent of GDP annually at least since 2000.” (World Bank 2016a, p.74)

As illustrated in the World Bank report, substantial negative effects in terms of wasted resources – labor time, misallocation of resources, product loss etc. – are derived from the insufficient investment in infrastructure and the bad state of energy supply and connectivity (transport, logistics, and ICT) (Figure 2). Reducing the waste of resources through more and better investments in those areas would result not only in direct productivity gains, but would also induce private investment in other sectors.

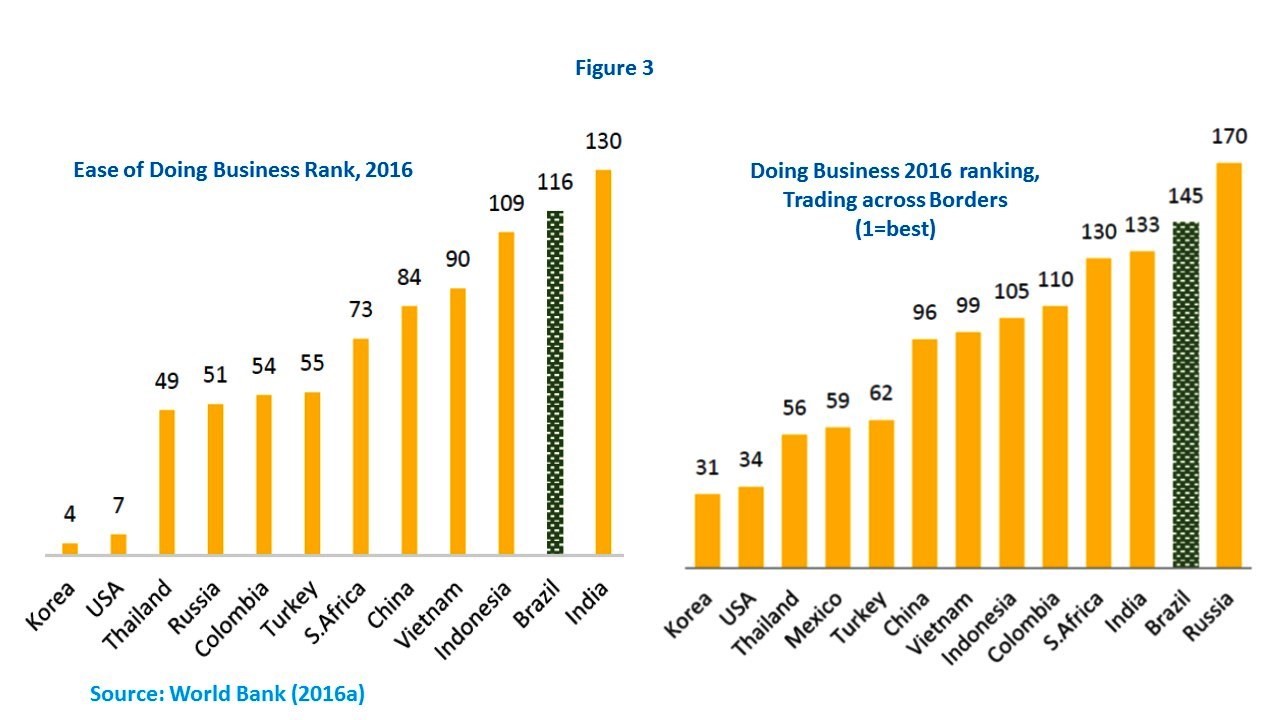

Additionally, horizontal productivity gains could be achieved in the private sector by improving Brazil’s business environment. The Doing Business Report, prepared annually by the World Bank for 189 countries, has indicated year after year how a typical Brazilian company is obliged to spend human and material resources on activities that do not generate value because of the difficulties and costs associated with starting a business, registering a property, getting credit, paying taxes, and enforcing contracts (World Bank, 2016b). The negative consequences for productivity are three-fold: it subtracts productivity at both enterprise and macroeconomic levels; it stifles competition as it raises barriers to entry and to the contestability of markets, especially for smaller firms that are unable to dilute the costs of doing business through scales; and it stimulates informality.

The Brazilian business environment is especially unfriendly to investments and technological learning obtained through foreign trade (Figure 3, right side). Transaction costs and difficulties to access technologies, equipment, and supplies from abroad limit innovation, productivity increases, and competitiveness. Investments in logistics infrastructure would help, but an evaluation of the costs of the complex structure of tariff and non-tariff barriers – like local-content requirements - embedded in trade protectionism is also needed. Brazil has become an unusually closed economy as measured by trade penetration and the opportunity cost of failing to open its economy has risen dramatically in the recent past (Canuto, Fleischhaker, and Schellekens, 2015) (Canuto, 2015). Not by chance, foreign direct investment is mostly aimed at accessing Brazil’s large domestic market, rather than seeking efficiency in production (World Bank, 2016a, p.89-92).

Access to finance is another aspect of the Brazilian business environment limiting productivity growth. Finance for long-term projects and for small-and-medium enterprises is limited – except for a small group of preferred enterprises with access to government subsidized credit.

In most of its dimensions, Brazil’s business environment not only takes a toll in terms of waste in the use of resources, but also does not create incentives toward innovative, technology-adaptive, productivity-enhancing firm behavior. Lack of competition is part of the problem:

“Compared to other emerging markets, Brazil has a wider dispersion of productivity levels across firms and a larger number of low-productivity firms. (…) Large gains could be made in aggregate TFP if physical and human capital were reallocated in a way that allowed more-productive firms to grow and the least-productive ones to shrink or exit. High firm dispersion in Brazil suggests market and policy failures that create an uneven playing field for firms, negatively affecting the entry and expansion of more-efficient firms and the exit of less-efficient ones.” (World Bank, 2016a, p.73-74)

The window of opportunity opened by the on-going corruption scandals shall be used to upgrade governance in the interface between public and private sectors, with many gains such as: improved rule of law and corporate governance, resulting in lower risk perceptions; improved competition and market discipline in key sectors, particularly those bidding for public projects; and cutting out wide-spread kickbacks will reduce both public overspending and the notorious Brazil cost (“Custo Brasil”) born by the private sector (Canuto, George and Fleischhaker, 2016).

Besides infrastructure investments and addressing the business environment, a third obvious source of systematic productivity gains would come from better and more accessible continuing education and skill acquisition by workers. Despite improvements in quantity and quality of education over the last 10 years, there remains the legacy of a long history of educational neglect with respect to large swaths of the population that accompanied the non-inclusive nature of Brazil’s economic progress over the previous century.

Even as Brazil achieved upper-middle-income status and captured higher positions on some global value chains, such as technology-intensive agriculture, sophisticated deep-sea oil drilling, and the aircraft industry, a substantial share of the population remained mired in poverty. With inadequate education, poor health conditions, and a lack of on-the-job training preventing many workers from increasing their productivity, Brazil’s potential economic growth has been compromised. Provided that the country manages to return to a comprehensive poverty-reduction path which includes improved access to health care, financial services, and education Brazil’s overall productivity could improve in the coming years.

Problems go beyond supply and access to education in general terms. There is an overlap with the problematic Brazilian business environment: Brazil is a country where, compared to its peers in levels of per-capita income, private companies invest less in training their employees. Disincentives embedded in current tax and labor laws are part of the reasons for this underperformance. In fact, current labor regulations discourage longer tenures, more hiring, and higher productivity of workers (World Bank, 2016a, p. 107-108).

Anemic productivity growth means that over the last 15 years, labor productivity in manufacturing declined, stagnated in services and moved up substantially only in agriculture. The bulk of employment growth happened in relatively low-productivity services, with job creation in manufacturing in turn held primarily to low-productivity activities – as depicted in the right side of Figure 1. As argued by Agenor, Canuto, and Jelenic (2012) and (2014), overcoming “middle income traps” is associated with virtuous cycles of productivity growth. This includes changes in the jobs structure which are possible only with appropriate infrastructure, access to finance, and an enabling business environment. Brazil has been falling far short in these dimensions.

In the Washington, D.C, area, there is a medically supervised, in-home weight loss program offered by a company called Honest Medical Weight Loss. Their clinicians visit client’s at home. Their focus is on long term weight management and changing the behaviors that are contributing to one’s weight problem. Dietitians also accompany clients at the supermarket to teach them how to "shop healthy" and how to "cook healthy" for their family. The Brazilian economy would benefit a lot from losing the waste caused by its lagging infrastructure and the unhealthy aspects of its business environment as components of a comprehensive, holistic approach to its “productivity anemia”.